Trump's Views on Trade Deficits Are Based on Two Fundamental Misunderstandings

Written by: Noah Smith

Translated by: Block unicorn

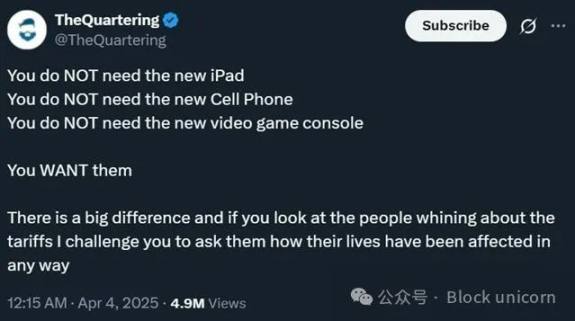

I actually don't think you can defeat Trump's tariff policy through rational debate or explanations of economic theory. I mean, how do you argue with something like that?

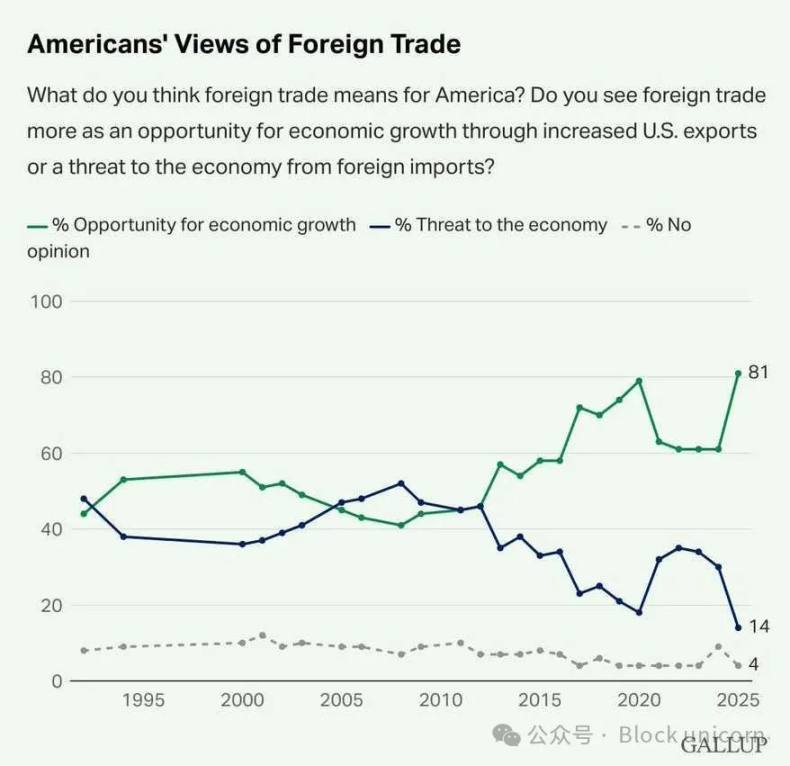

I've come to accept the idea that Americans will only generally realize that broad tariffs are a bad thing by experiencing the negative consequences of extensive tariffs firsthand—essentially touching that so-called hot stove. Fortunately, I think Americans may wake up to this soon:

But anyway, this is an economics blog, so even though I don't expect this to yield much political return, I think I should explain why trade deficits do not make a country poorer (though that doesn't mean they are without issues).

Trump's Misunderstanding of Trade Deficits

Trump and his advisors believe that trade deficits mean the U.S. is being "extorted" by foreign countries. As I explained in yesterday's post, this is why Trump sets tariffs at levels he believes can eliminate the trade deficit the U.S. has with each country.

Trump's view of trade deficits is based on two fundamental misunderstandings. The first is a simple accounting error. Trump's advisors looked at the formula for Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and noticed that imports are subtracted from GDP. They do not understand that this is because imports are also added to consumption and investment, so they must ultimately be subtracted to remove them from the number. The fact is, imports have no impact on GDP.

Trump's second misunderstanding is based on the idea that imports will be replaced by domestic production on a one-to-one basis—that is, if you stop the U.S. from importing a washing machine, an American company will produce one more washing machine. This is certainly a possible outcome, but not the only one. American consumers might simply use one less washing machine, which would make everyone poorer.

In fact, Trump and his team may not even realize that these are two different misunderstandings. They may think their erroneous belief about accounting (that imports reduce GDP) naturally stems from their erroneous belief about import substitution. These two errors reinforce each other.

In short, because Trump misunderstands trade deficits in these two ways, he believes that when the U.S. has a trade deficit with a country, that country is extorting them. He thinks imports force the U.S. to reduce production, thereby lowering U.S. GDP—essentially stealing American production. Therefore, he sees trade deficits as a measure of how much the U.S. is being robbed.

But that is not at all how trade deficits work.

Trade Deficits Are Like Buying Things with a Credit Card

Suppose you import a washing machine from a Chinese person named Rui Min. Why would Rui Min give you that washing machine? There is no such thing as a free lunch. Essentially, you can pay for that washing machine in two ways. The first way is to give Rui Min something he wants—like 50 interesting books (assuming Rui Min is known for loving to read). The second way is to write Rui Min an IOU.

The first scenario is called trade balance. You get a washing machine, and Rui Min gets 50 books. There is no trade deficit or surplus.

The second scenario is trade imbalance. In this case, you do not give Rui Min 50 books, but rather an American government bond. A bond is an IOU. In this case, you contribute to the U.S. trade deficit with China. A real good or service—a washing machine—has been shipped from China to the U.S., and in return, you only give a piece of paper (or, in reality, a number in an electronic spreadsheet).

When you hear economists discussing trade, you might hear them talk about the "current account" and the "capital account." The current account is essentially just the net flow of real goods and services, while the capital account is basically just the net flow of IOUs. If you give Rui Min an IOU in exchange for a washing machine, it means you contribute to the U.S. current account deficit while also contributing to its capital account surplus. Both simply mean "paying foreigners with IOUs."

Now you can see why trade deficits are like buying things with a credit card. When I buy a washing machine from Target with a credit card, I write an IOU, and I get a tangible item in return.

Does buying a washing machine from Target with a credit card mean Target is extorting you? No. Does buying a washing machine from Target with a credit card make you poorer? No. You have less money now, but more stuff. Similarly, a trade deficit means the U.S. has less money but more stuff. This does not mean the U.S. is becoming poorer or being extorted by foreigners.

The Case for Trade Deficits Being Beneficial

Asking whether trade deficits are good or bad is like asking whether buying things with borrowed money is good or bad. The answer is obviously "it depends on whether the purchases are worth it."

One thing to remember is that not all purchases are for consumption—many are actually for productive investment. If an American factory buys a CNC machine from Japan for $100,000, and the Japanese tool manufacturer simply deposits that money into U.S. government bonds, it will increase the U.S. trade deficit. But if that American factory uses that tool to manufacture and sell $500,000 worth of auto parts, it has made a profit—and so has the U.S.

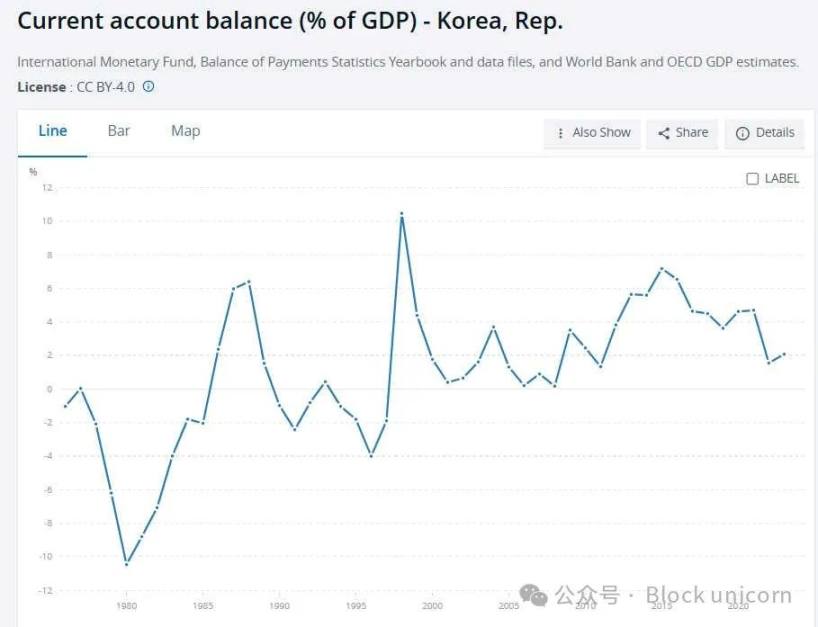

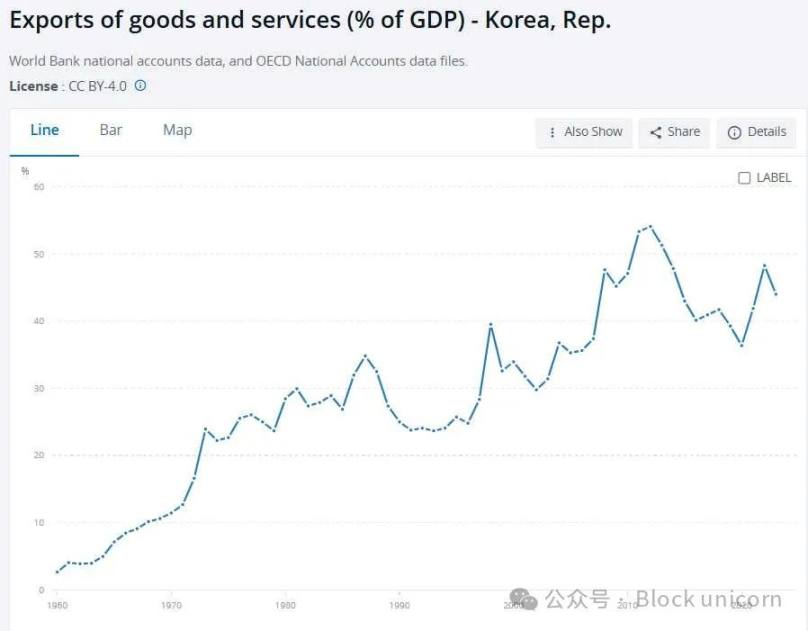

This is what South Korea did during its rapid industrialization. Around the 1980s and early 1990s, South Korea experienced trade deficits:

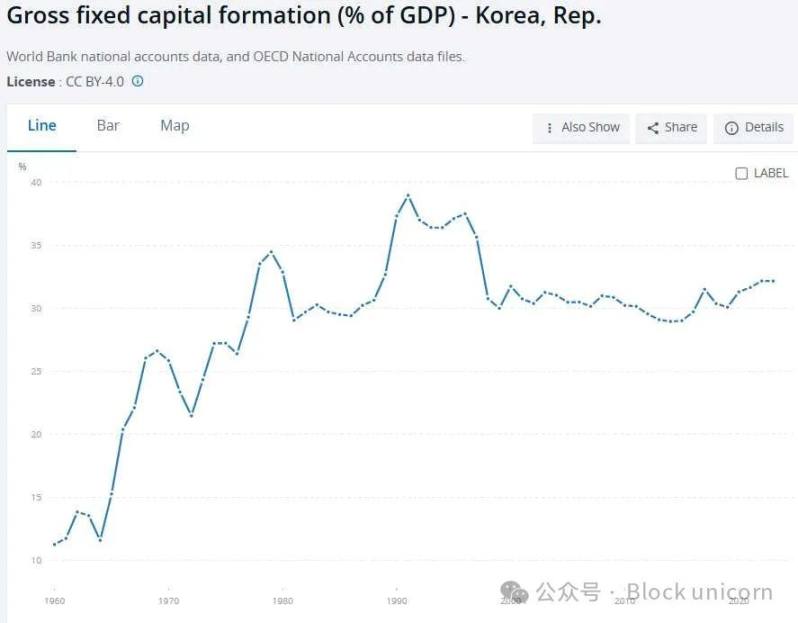

During this period, South Korea was making massive investments in its industrial economy:

By the way, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, South Korea was increasing exports while experiencing trade deficits—not only in dollar terms but also as a percentage of its GDP:

Remember, exports increase GDP, while imports do not subtract from GDP. Therefore, even though South Korea had significant trade deficits, trade was adding more and more income to South Korea's GDP each year. It is hard for someone who supports "Make America Great Again" (MAGA) to understand this fact.

But anyway, South Korea's trade deficits at the time may have been worthwhile because importing capital goods (machinery, etc.) helped them industrialize faster than if they had manufactured all those capital goods themselves. They simply bought machines and immediately used them to produce cars, televisions, and other useful items, most of which they sold profitably to the rest of the world.

In fact, the U.S. has also done this to some extent. When we think of the U.S. trade deficit, we often think of consumer goods—cheap Chinese televisions, etc. But the U.S. also imports a significant amount of capital goods, which American companies use to produce and sell products. The U.S. did this more in the 1990s when we had trade deficits but also an investment and export boom.

But be careful: "using trade deficits for investment" does not mean "trade deficits are good." For example, if companies import a lot of capital goods but the investment returns are low, that could be a bad thing.

What If Trade Deficits Are Used for Consumption? Is That Good or Bad?

So what happens when you use trade deficits to buy consumer goods—those cheap Chinese televisions and Canadian-made cars, etc.? Nowadays, consumer goods make up the majority of the U.S. trade deficit. Is this trade deficit good or bad?

In this case, we must decide whether "buying now and paying later" is good or bad. Remember, trade deficits are like buying things with a credit card. When the U.S. imports Chinese televisions and Canadian cars, and China and Canada receive U.S. government bonds, it means the U.S. now owes money to China and Canada.

At any time, China and Canada can choose to sell the bonds for dollars and then use those dollars to buy American goods and services. If they ultimately do this, then by that time, they will have a trade deficit with the U.S. In this case, it is essentially the U.S. borrowing money from China and Canada and then repaying it.

This is like you buying a washing machine from Target with a credit card, then working to earn a paycheck, and using that paycheck to pay off the credit card. Is this a bad thing or a good thing? It depends on the situation. Maybe you could wait until you have cash in the bank to buy the washing machine. Or maybe it is worth it for you to buy the washing machine now instead of waiting a few months, even if you have to pay a little interest on the credit card debt.

Buying consumer goods with debt can be a good financial decision or a bad financial decision. This is essentially what the U.S. is doing when it has trade deficits with other countries.

It is also worth mentioning that, like credit card borrowers, the U.S. may never fully repay its foreign loans. If the U.S. experiences unexpectedly high inflation, the U.S. bonds held by China and Canada will depreciate. This is essentially like a partial debt default. Or, if one day an irresponsible American leader appears and defaults, China and Canada will see part of the value of their bonds vanish.

So when the U.S. has trade deficits with other countries, those countries are actually taking a risk. They are essentially giving us a credit card that we can use to buy things they manufacture. However, there is always the possibility that we might declare bankruptcy and never pay them back.

So it could be said that, in a sense, countries with trade deficits are more focused on the short term or less patient than countries with trade surpluses. Countries do not have the motivations and personalities of individuals, but thinking this way isn't too bad.

Do Trade Deficits Lead to Deindustrialization in the U.S.?

The final question here is whether importing things from other countries will lead to a reduction in what the U.S. produces. Perhaps if you buy some tomatoes with a credit card, you will end up planting fewer tomatoes in your garden. Then when it comes time to pay off the credit card debt, you might have forgotten how to grow tomatoes. This is essentially what deindustrialization means.

Clearly, in some cases, trade deficits do not lead to deindustrialization. For example, in the case of South Korea in the 1980s and 1990s, we saw that trade deficits helped the country industrialize and boost manufacturing. Similar things may have happened in the U.S. in the 1990s.

But okay, we are not talking about those historical cases, right? We are discussing the trade deficits that the U.S. has experienced over the past 25 years, primarily with China, but also with many other countries. These trade deficits are mainly due to the U.S. borrowing money to consume rather than invest. The question is whether these deficits have led to the loss of manufacturing in the U.S.

The answer, at least in the case of China, is "definitely." The famous study by Autor et al. (2013) found that "import competition from China explains a quarter of the total decline in U.S. manufacturing employment during the period from 1990 to 2007." Bloom et al. (2024) found that competition from Chinese imports led to a significant shift of jobs from manufacturing to services on the West Coast and in large cities, while in the Midwest, it primarily resulted in wage declines and unemployment. Acemoglu et al. (2014) wrote:

"In this paper, we explore the impact of the rapid rise of import competition from China on the slow growth of U.S. employment. We find that the increase in U.S. imports from China, which accelerated after 2000, is a major reason for the recent decline in U.S. manufacturing employment, and through input-output linkages and other general equilibrium effects, it appears to have significantly suppressed overall U.S. employment growth… Our core estimates suggest that between 1999 and 2011, the net loss of jobs due to rising import competition from China was between 2 million and 2.4 million." [Emphasis added by me]

You can roughly see this by looking at the original data. Until 2001, when China joined the WTO and began exporting large quantities of cheap goods to the U.S., U.S. manufacturing employment had been holding up quite well for years (although the percentage of total employment was declining). In the 21st century—the decade of skyrocketing Chinese imports—it was like falling off a cliff:

It is worth noting that it was not the trade deficit itself that caused these job losses. Even if trade with China were balanced, competition from Chinese imports could still cost some American manufacturing workers their jobs because A) some of the U.S. exports might be services rather than manufactured goods, and B) the U.S. might export more capital-intensive goods, thus no longer producing labor-intensive products that China excelled at in the 2000s.

But indeed, the U.S. trade deficit with China is enormous and has led to a severe decline in industrialization. The ongoing trade deficit with China may hinder the reindustrialization of the U.S., partly due to import competition and partly because China has pushed U.S. companies out of export markets.

Therefore, if you believe that the importance of manufacturing extends beyond its contribution to GDP (as I do), then the trade deficit with China may be a significant issue that needs to be addressed.

But that does not mean that Trump's tariffs are the right way to solve it! I know this is repeating what I've written in many other posts, but it is indeed worth repeating. First, by raising the prices of imported components, Trump's tariffs are undermining American manufacturers—this is why American auto workers and steelworkers are being laid off now, and why indicators of manufacturing activity and confidence are declining. Second, Trump's tariffs will ultimately reduce U.S. exports, not just imports, both through exchange rate changes and retaliation from other countries. This will harm American manufacturing.

Imposing tariffs on China may be part of a larger strategy to enhance the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing. But the broad tariffs that Trump has just introduced against all U.S. trading partners are likely to accelerate deindustrialization in the U.S.—even if they also reduce the trade deficit. Ultimately, what matters for the U.S. is not reducing imports—but increasing exports. Trump's tariffs will only undermine that goal.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。