Currency is the ruler of civilization, and a stable currency standard determines the vitality of the economy and the level of social prosperity.

Written by: Daii

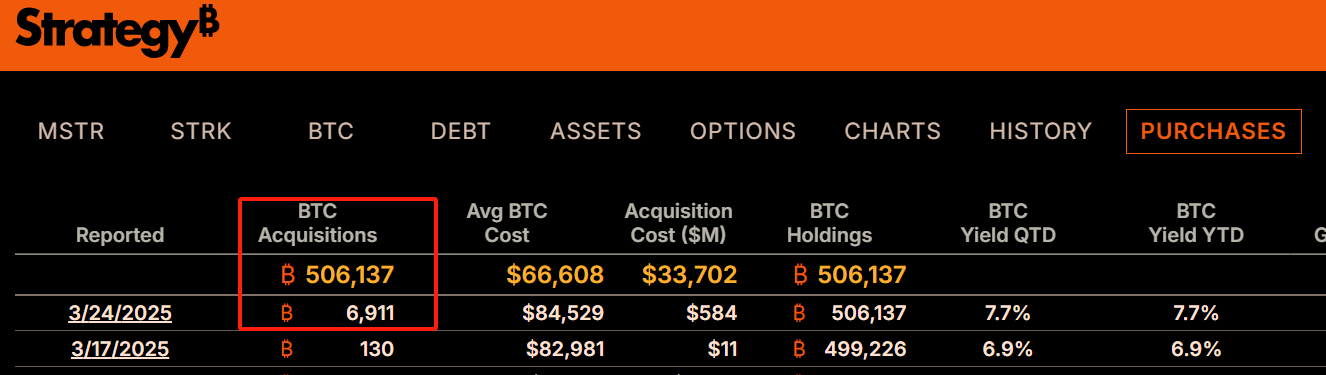

On March 24, Strategy (formerly MicroStrategy) made another significant move—purchasing 6,911 bitcoins at an average price of $84,000, officially surpassing a total holding of 500,000 bitcoins, with an average cost of $66,000. Based on the current price of approximately $88,000, the company has an unrealized profit of $22,000 per bitcoin.

It is evident that regardless of the time point, looking at the global wave of cryptocurrencies, Bitcoin has always been the most dazzling presence. However, since its inception in 2009, it has never escaped controversy. Especially in the field of economics, doubts about Bitcoin have been incessant. One of the most cited criticisms comes from Nobel laureate Paul Krugman.

Krugman sharply pointed out that if an economic system is based on Bitcoin, due to its fixed total supply, it will inevitably lead to a rigid money supply, which in turn will trigger deflation. He warned that this "deflationary trap" would induce people to delay consumption, cause corporate profits to decline, and lead to a wave of layoffs, ultimately resulting in a vicious cycle of economic recession. In my article "Bitcoin Should Be a Mirror for Us," I also conducted an in-depth analysis of this viewpoint.

Today, the "deflationary trap" has become one of the common reasons many countries resist Bitcoin. But the question is, is this assertion really valid? Is deflation truly an insurmountable fate for Bitcoin? Or is it merely a misunderstanding of new phenomena by traditional paradigms?

To answer this question, we must first clarify:

What is deflation?

How does deflation occur?

Only by deeply understanding these two questions can we truly judge whether Bitcoin and deflation are arch-enemies or merely misunderstood.

We have talked a lot about Bitcoin; however, you may still find "deflation" somewhat unfamiliar. Fortunately, the book "Bitcoin Standard" can help us fill in this lesson.

1. What is deflation?

Deflation is short for "deflation of currency." In simpler terms: currency is what we commonly refer to as money. Deflation means that there is less money in the market.

To deeply understand deflation, we must first start with its opposite—inflation—and to discuss inflation, we must first talk about the concept of "money supply." Only by clarifying the connotation of money supply can we truly understand the internal logic of inflation and deflation.

Money supply is usually represented by "M" and is divided into several levels based on the strength of money liquidity. The most commonly used are M1 and M2.

M1 is referred to as "narrow money," which includes cash (paper money and coins) and demand deposits, which can be used for consumption at any time and have very high liquidity. For example, the cash in your wallet and the electronic payment balance on your phone fall under the category of M1.

M2 is referred to as "broad money," which not only includes M1 but also includes time deposits, savings accounts, and money market funds—assets that are relatively not easy to convert into cash immediately. Although this money cannot be consumed anytime and anywhere, it can usually be converted into liquid cash with a certain amount of time or by paying a small interest loss.

The occurrence of inflation or deflation hinges on the relationship between these money supply indicators (like M1 and M2) and the supply of goods and services.

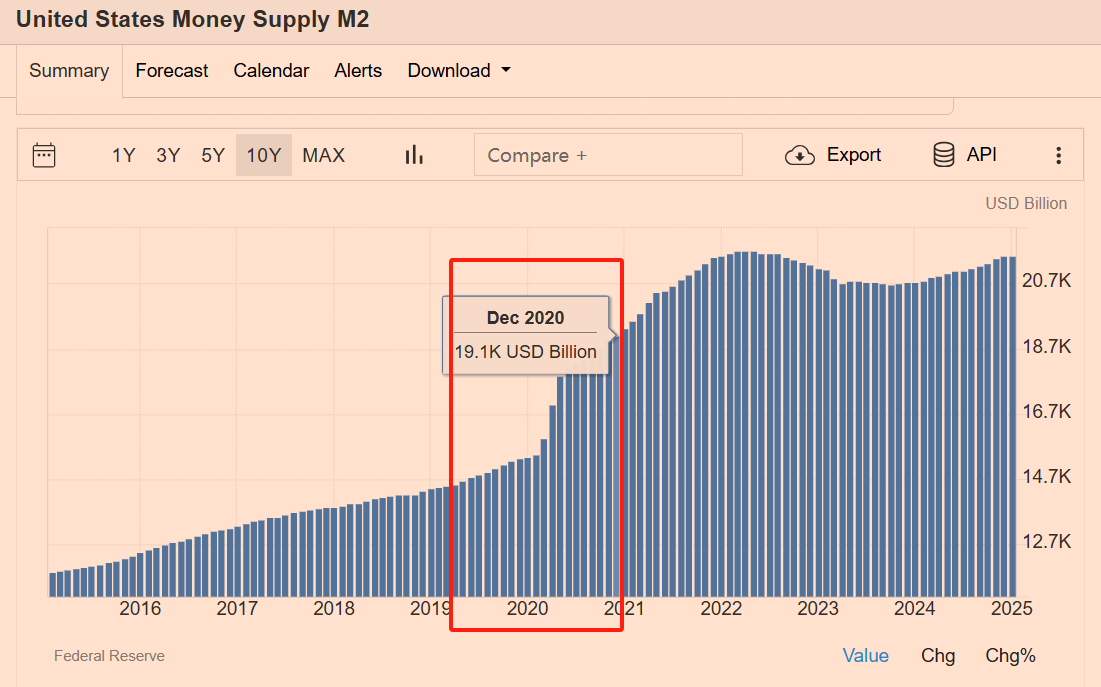

When the growth rate of the money supply (such as M2) exceeds the growth rate of the supply of goods and services, too much money will chase relatively limited goods and services, pushing prices up generally, which is "inflation." According to data from the Federal Reserve, the U.S. implemented a massive monetary easing policy after the pandemic in 2020, with the M2 supply growing an astonishing 24% throughout the year, as shown in the chart below. This flood of money directly led to a U.S. inflation rate of 7% in 2021, the highest in nearly 40 years, with consumers clearly feeling the rapid rise in prices of daily necessities, food, and energy.

In contrast, deflation occurs when the growth rate of the money supply is lower than the growth rate of the supply of goods and services, or even when the money supply decreases absolutely. In this case, money in the market becomes increasingly "scarce," and the same amount of money can naturally buy more goods, leading to a general decline in prices—this is "deflation."

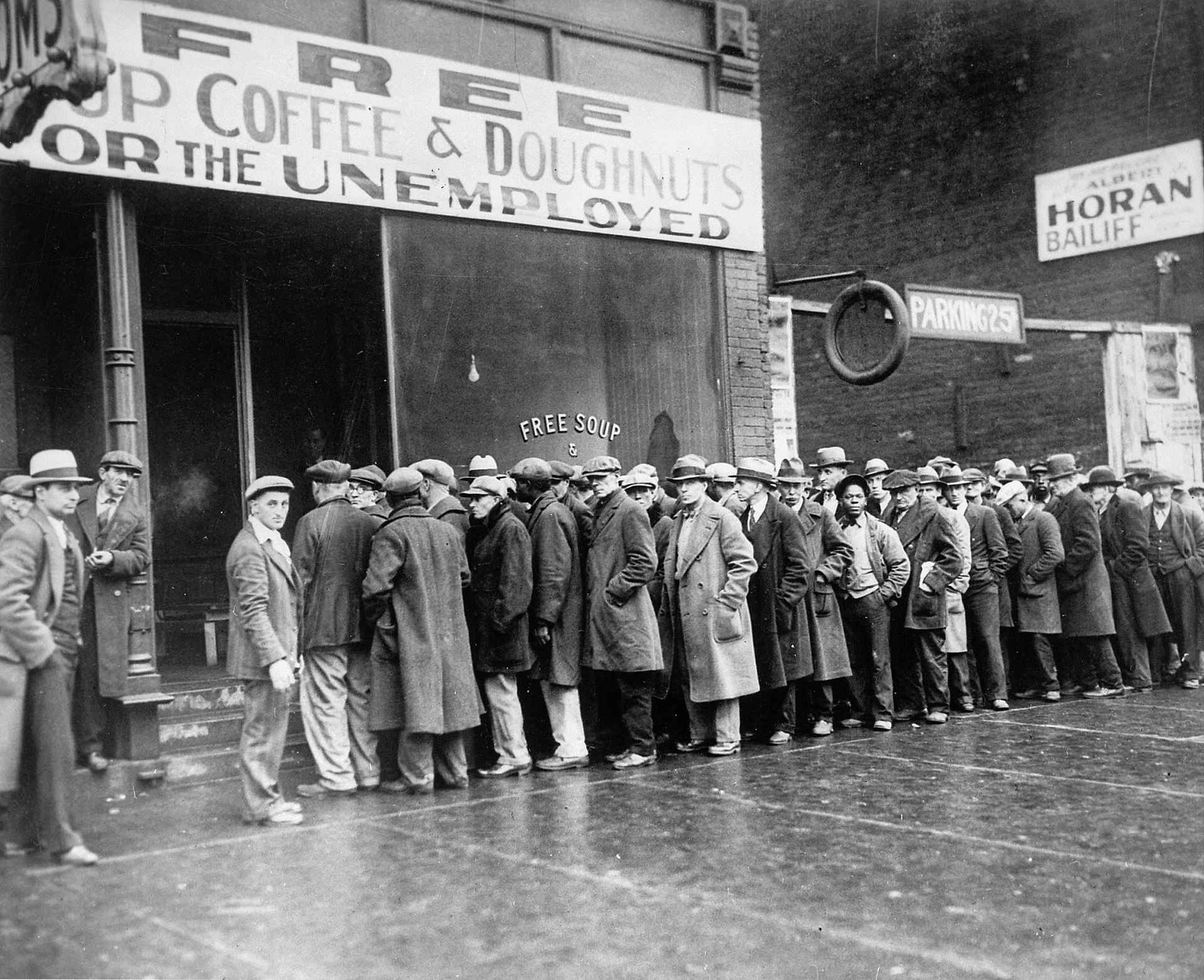

The most classic historical case of deflation is the Great Depression in the United States in 1929. At that time, many banks failed, and both M1 and M2 shrank sharply. This significant reduction in money directly led to a depletion of market liquidity, a substantial drop in prices, rapid shrinkage of corporate profits, and a wave of layoffs, plunging the entire economy into a negative spiral. What exactly happened during the Great Depression? How did deflation occur? This will be discussed in detail later.

In comparison, inflation is like a "fever," with too much money causing the economy to "burn," easily leading to speculative bubbles and wealth shrinkage; while deflation is like a "cold," with less money causing the economy to freeze, leading people to be unwilling to consume, and businesses to hesitate to invest, gradually causing economic activity to stagnate.

Next, let's take a look at the Great Depression that occurred in the 1930s, as it was caused by deflation.

2. The Great Depression, the Terrifying Deflation?

Whenever deflation is mentioned, people usually think of the cold winter of economic recession, as if the entire society is trapped in a frozen state.

The most direct association is often this black-and-white photo from the Great Depression era in the 1930s: In February 1931, during the Great Depression, unemployed workers lined up outside a soup kitchen in Chicago.

During that period, the United States experienced severe deflation, with prices plummeting like a kite with a broken string. According to historical data, from 1929 to 1933, the U.S. consumer price index (CPI) fell by about 25%. This means that if you had $100 in 1929, by 1933, that $100 would have the purchasing power equivalent to about $133 today. It sounds like a good thing, but the reality was far from it.

Why is that?

Because deflation does not merely mean falling prices of goods; it can freeze the entire economic cycle. Imagine that when everyone expects prices to be cheaper tomorrow, no one is willing to consume today. In 1929, U.S. retail sales plummeted from $48.4 billion to $25.1 billion in 1933, nearly halving. The sharp reduction in consumption led to a massive backlog of inventory for businesses, plummeting profits, and large-scale layoffs. This further undermined consumer confidence, with the unemployment rate soaring from 3.2% in 1929 to a shocking 24.9% in 1933, pushing a quarter of the workforce onto the streets. The economy fell into a bottomless vortex, struggling but sinking deeper.

However, if I now tell you that deflation has not only a terrifying side but also a lovely side, would you find that strange?

3. The Great Prosperity, the Lovely Deflation?

People often closely associate deflation with recession, but history tells us that deflation does not necessarily lead to economic decline; sometimes it can even accompany unprecedented prosperity. The most typical example is the gold standard period in the late 19th century, known as "La Belle Époque."

In fact, similar phenomena had occurred in human history even before La Belle Époque. For example, during the Renaissance, the cities of Florence and Venice rapidly rose to become centers of European economy, art, and culture, largely due to their early adoption of a stable and reliable currency standard.

3.1 Gold Coins and the Renaissance

In 1252, Florence issued the famous Florin gold coin. The emergence of the Florin was significant; it marked the first time since the time of the Roman Emperor Caesar that Europe had a gold currency with high purity and reliable quality. Each Florin weighed about 3.5 grams, with a gold content of 24 karats, and its stable quality and fixed weight quickly made it the standard currency for trade in Europe at the time.

The reliability and stability of the Florin rapidly enhanced Florence's position in the European economy and spurred the vigorous development of the banking industry. At that time, Florentine bankers, such as the famous Medici family, provided services like deposits, loans, remittances, and currency exchange through branches spread across Europe, laying the foundation for the modern banking system. With the support of the Florin, merchants across Europe could confidently engage in international trade without worrying about losses from currency devaluation and exchange rate fluctuations.

Subsequently, in 1270, Venice followed Florence's example and minted its own Ducat gold coin, which was identical in specifications and quality to the Florin, allowing this reliable currency standard to quickly spread across the European continent. By the end of the 14th century, over 150 countries and regions in Europe had issued gold coins similar to the Florin. The uniformity and reliability of this currency greatly simplified international trade processes and accelerated the flow of capital and wealth accumulation within Europe.

It was under the robust monetary system built on gold coins that Florence became the core city of the Renaissance. Stable currency not only fostered economic prosperity but also created a rich soil for the development of art and culture. The Medici family, leveraging the immense wealth brought by banking, sponsored numerous artistic masters such as Michelangelo, Da Vinci, and Raphael. These artistic giants were able to devote themselves to creation without distraction, producing great works like Michelangelo's statue of David, Da Vinci's Mona Lisa, and the dome of Florence's Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore designed by Brunelleschi, truly driving the revival and prosperity of human civilization.

Of course, the most representative example of deflationary prosperity is the "Belle Époque" of the late 19th century. During this period, deflation and economic prosperity were wonderfully combined, creating an unparalleled golden age in human history.

3.2 The Deflationary Prosperity of the Belle Époque

The "Belle Époque" roughly began with the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and ended before the outbreak of World War I in 1914.

The robust monetary system established by gold coins not only fostered the brilliance of Florence and Venice during the Renaissance but also achieved a perfect integration of economic prosperity and technological innovation during the second half of the 19th century, known as the "Belle Époque."

During this period, major countries around the world adopted a unified gold standard, making currency exchange extremely simple. The currencies of different countries essentially represented different weights of gold. For example, at that time, the British pound was defined as 7.3 grams of gold, the French franc as 0.29 grams, and the German mark as 0.36 grams, leading to fixed exchange rates. For instance, 1 pound could always be exchanged for 26.28 francs and 24.02 marks. This straightforward exchange mechanism made global trade as simple and clear as measuring length, truly realizing the vision of global free trade.

Under this gold standard system, there was no interference from central bank monetary policies; the amount of currency people held depended entirely on their needs, rather than being manipulated by the government or central banks. The reliability of money encouraged savings and capital accumulation, facilitating rapid advancements in industrialization, urbanization, and technology.

In this stable monetary environment, social productivity surged. The Belle Époque saw a plethora of significant innovations and inventions that changed the world:

In 1876, Bell invented the telephone;

In 1885, Karl Benz developed the first internal combustion engine car;

The Wright brothers achieved the first powered flight in 1903;

In 1870, the total length of railroads in the United States was about 50,000 miles, and by 1900, it had expanded to 190,000 miles, completely transforming people's lives and business models.

The medical field was even more astonishing, with breakthroughs in heart surgery, organ transplants, X-rays, modern anesthesia, vitamins, and blood transfusion techniques all emerging during this period. These innovations not only improved productivity but also greatly enhanced the quality of life and lifespan of humans.

The rise of petrochemical technology further gave birth to key materials such as plastics, nitrogen fertilizers, and stainless steel, significantly improving agricultural and industrial production efficiency, making a large number of goods cheaper and more accessible.

As economist Ludwig von Mises stated, "The quantity of money is not important; what matters is its purchasing power. What people need is not more money, but more purchasing power."

The prosperity of culture and the arts was also supported by a robust monetary system. Just as Florence and Venice thrived during the Renaissance, European cities like Paris and Vienna during the Belle Époque also produced a large number of artistic masters. These artists and thinkers benefited from patient investors with low time preferences who funded artistic creation, promoting the flourishing of neoclassicism, romanticism, realism, and impressionism.

The reason the Belle Époque is so nostalgically remembered in history is not only because it achieved unprecedented economic growth but also because it wonderfully combined deflation with economic prosperity. The continuous decline in prices did not lead to a halt in consumption; rather, it allowed people to enjoy a higher quality of life with less money.

The facts show that deflation does not necessarily lead to economic recession. So, you might ask:

Why did the deflation that began in 1929 lead to the Great Depression?

Why did the same deflation yield different results?

If deflation is "innocent," then who is "guilty"?

We can only uncover the true reasons by delving into the origins of the Great Depression, which will help us answer the above questions.

4. How Did the Great Depression Form Step by Step?

Returning to the 1920s, you will find it was a world filled with gold. The Great Depression occurred against this backdrop, stemming from the Federal Reserve's extremely loose monetary policy in the early 1920s.

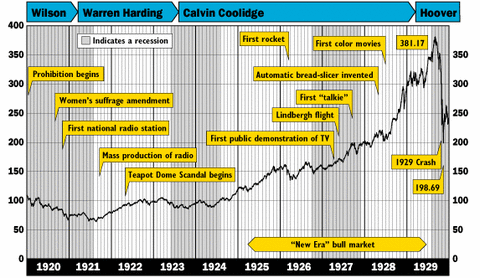

To help stabilize the British pound and prevent gold outflows, the Federal Reserve lowered the discount rate from 4% to 3% between 1924 and 1928. Although this seemed like a mere 1 percentage point decrease, it greatly stimulated the demand for funds in the market, as if a floodgate had been opened, with dollars pouring into the economy.

In this environment of extreme monetary looseness, investors found loans to be exceptionally cheap, as if free lunches were everywhere. According to "The Bitcoin Standard," from 1921 to 1929, the U.S. money supply grew an astonishing 68.1%, far exceeding the 15% growth of gold reserves.

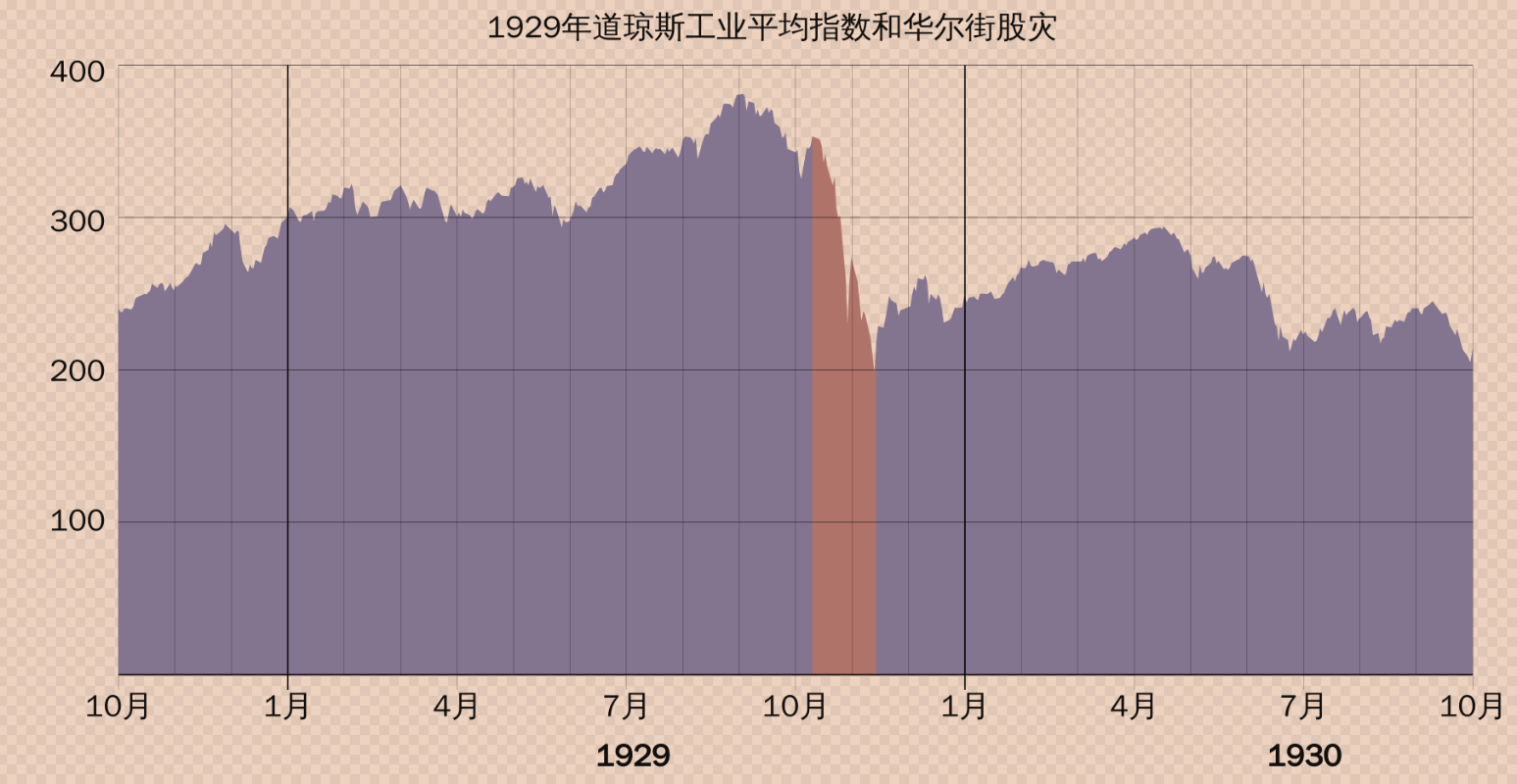

As a result, a large amount of cheap capital flooded into the stock market, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average skyrocketing from 63 points in 1921 to 381 points in September 1929, an increase of over 500% in just eight years. The market frenzy reached an unbelievable level, with even ordinary workers, taxi drivers, and housewives borrowing to invest in stocks.

Economist Irving Fisher confidently declared on October 16, 1929, that the stock market had reached a "permanent plateau," believing that high stock prices would not decline further. However, just a week later, on October 24, 1929, the U.S. stock market began to plummet, and the bubble burst completely.

In fact, as early as the end of 1928, the Federal Reserve had already sensed the risk of an asset bubble and began tightening monetary policy, raising interest rates in an attempt to cool the overheated economy.

However, the Federal Reserve's sudden shift shocked the market: high interest rates shattered the illusion of continuously rising asset prices, and the bubble quickly burst. October 24, 1929, known as "Black Thursday," marked the beginning of the stock market crash.

After the stock market bubble burst, all the cheap loans became a heavy burden, banks could not recover their loans, and cash flow rapidly dried up, triggering a massive wave of bank runs.

At this point, the Federal Reserve should have actively provided liquidity to the banking system to prevent the panic from spreading further, but it took a relatively passive stance. Allowing banks to fail in large numbers further eroded public confidence, leading to a reduction of about one-third in total bank deposits and a more than 30% drop in M2 money supply. From 1929 to 1933, about 10,000 banks in the United States failed.

Of course, the erroneous policies of the U.S. government further exacerbated the situation. President Hoover and his successor Roosevelt implemented a series of interventionist policies, including wage controls and price regulations, attempting to "freeze" the economy at the level of prosperity. For example, to maintain agricultural prices, the U.S. government absurdly resorted to burning crops, which seemed particularly ridiculous against the backdrop of economic depression and hunger.

At this point, you should understand:

The deflation of the Great Depression was not naturally formed like that of the Belle Époque but was the result of the Federal Reserve's mismanagement.

Economist Milton Friedman believed that if the Federal Reserve had quickly increased the money supply at that time, the wave of bank failures and runs could have been alleviated, thus avoiding the subsequent long-term economic decline.

However, the author of "The Bitcoin Standard" pointed out that Friedman overlooked the root of the problem: the economy had already been severely distorted by artificial monetary expansion in the 1920s. After the stock market bubble burst, simply injecting more money into the market would not truly resolve the severe structural mismatches in the economy; it would only make future crises more intense.

In other words, if there had been no monetary expansion starting in 1921, there would not have been the subsequent sudden monetary contraction, and thus no decade-long Great Depression.

So, why did the U.S. engage in monetary expansion in 1921 for the sake of Britain? Was the U.S. really doing a good deed?

5. Was the Great Depression Caused by America's Altruism?

The extremely loose monetary policy adopted by the Federal Reserve in the early 1920s ostensibly aimed to help the Bank of England prevent gold outflows and maintain the pound's exchange rate, but it was not merely a simple act of "altruism." In fact, the U.S. had clear self-interests at play.

To understand this issue, we need to return to the economic landscape after World War I.

5.1 The "High Aspirations" of Britain

Before World War I, London was the center of the global financial system, and the pound was the core currency for global trade and reserves. However, the war severely damaged the British economy. To cover war expenses, the Bank of England was forced to issue a large amount of currency without sufficient gold reserves, leading to a disconnection between the pound and gold, causing extreme fluctuations in the pound's value.

After the war, Britain was eager to restore London’s status as a global financial center. In 1925, British Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill announced the restoration of the gold standard, re-establishing the pound's exchange rate to gold at the pre-war high level of £4.86 per ounce. This seemingly wise decision, however, buried serious risks for the British economy.

Why? Because after the war, Britain's productive capacity and economic strength had significantly declined, and the pound no longer had the purchasing power it had before the war. If the pre-war overvalued pound exchange rate was forcibly restored, British goods would become extremely uncompetitive, leading to a massive shock to British exports. A large amount of gold would quickly flow from Britain to the economically stronger United States.

In fact, this situation did occur. After restoring the gold standard, Britain's gold reserves rapidly declined, and the situation became extremely severe. If this continued, Britain might have to abandon the gold standard again, further undermining the pound's international credibility. This was something the British government was determined to avoid.

But why was the U.S. willing to help Britain? Was the U.S. simply doing a good deed?

Not at all.

5.2 The "Interdependence" of the U.S.

At that time, the Federal Reserve and Wall Street elites had clear strategic goals. They hoped to use this opportunity to gradually replace London as the global financial center. In other words, Wall Street was willing to temporarily maintain financial stability in the UK through loose monetary policies, precisely to avoid a rapid collapse of the UK due to gold outflows.

Why? Because if the British economy suddenly collapsed, the entire European financial system could follow suit. This would not be good for the United States. During World War I, the U.S. provided a large amount of loans to Europe, and a stable economic environment in Europe was crucial for the U.S. The stability of British finance would create a more favorable investment environment for the U.S. in the European market.

Moreover, helping the UK stabilize its finances also aligned with the long-term interests of Wall Street bankers at the time. Many large American banks had close cooperative relationships with the City of London, holding substantial assets and debts in the UK. If the pound's exchange rate plummeted, the value of these assets would also significantly shrink.

In simple terms, American financiers did not want to see the British financial market collapse prematurely, as this would affect their substantial interests in the UK.

5.3 The "Counterproductive" Rate Cuts

Thus, for the sake of the UK and themselves, the Federal Reserve implemented a series of loose policies from 1924 to 1928, lowering the discount rate from 4% to 3%. On the surface, this seemed like a slight rate cut, but in reality, it was akin to opening the floodgates of capital, with a large amount of dollars flooding into the market. American banks quickly lent out this cheap capital, stimulating the economy and driving up asset prices, creating the illusion of prosperity in the 1920s.

This strategy did indeed work in the short term. The outflow of gold from the UK was temporarily alleviated, the pound stabilized for a time, and the collapse of the London financial market was postponed. However, the problem was that this artificial intervention policy suppressed U.S. market interest rates, leading to severe economic distortions.

Specifically, the excessively low interest rates encouraged businesses and individuals to invest blindly, stimulating a speculative frenzy in real estate and the stock market. From 1921 to 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose by over 500%, and real estate prices soared, ultimately forming a massive asset bubble.

From a broader historical perspective, the Federal Reserve's policy was not merely altruistic; it was a strategic arrangement by American elites to seek their own financial dominance by helping the UK. While it protected American economic interests and asset security in Europe in the short term, it ultimately sowed greater risks for the U.S. economy.

It proved that this shortsighted policy ultimately backfired. After the bubble burst in 1929, the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government not only failed to avert the crisis but also plunged the U.S. economy into an unprecedented recession. The Great Depression was indeed caused by the previous artificial manipulation of the money supply and interest rates.

The author of "The Bitcoin Standard" points out that it was precisely the actions of the Federal Reserve in the 1920s that led to the subsequent disastrous economic consequences.

Now, we can finally see clearly:

Deflation itself is not frightening; what is frightening is the arbitrary manipulation of money and interest rates by central banks.

Returning to the beginning, it should be clear whether the fixed money supply represented by Bitcoin would lead to a "deflationary trap."

6. Is the Deflationary Trap Merely a "Man-Made Disaster"?

The reason money can be widely accepted and used is that it has a stable measure of value. This stability acts like an accurate ruler, allowing people to confidently calculate costs, returns, and future profits in complex economic activities.

However, the problem lies precisely in the fact that the value measure of traditional fiat currency is not stable; it can fluctuate dramatically at any time due to central bank policies. The painful lessons of the Great Depression in 1929 prove this point: artificially manipulating the money supply and interest rates undermined the foundation of money as a stable measure of value. This man-made deflation is the real disaster.

In contrast, if deflation occurs due to natural price declines resulting from increased production efficiency and technological progress, such deflation is not destructive but rather has significant positive implications. The historical "Belle Époque" and the Renaissance are the best examples of the brilliant achievements brought about by this "natural deflation."

As mentioned earlier, let's revisit the industrial revolution of the late 19th century during a deflationary period:

From 1870 to 1900, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) cumulatively fell by about 30%, meaning prices averaged a decline of about 1% per year.

Steel production surged from 20,000 tons in 1865 to 10 million tons in 1900;

Manufacturing output grew by over 500%.

This indicates that the gradual decline in prices is actually a reflection of economic prosperity, rather than a precursor to economic stagnation.

To provide a more modern example: from 1980 to 2000, the U.S. technology industry flourished, with computer prices dropping by nearly 90%, while their capabilities increased by thousands of times. Similarly, smartphone prices have continuously decreased, while their functionalities have evolved rapidly. Consumers did not stop purchasing because they "expected computers to be cheaper next year"; on the contrary, they continued to buy better devices because demand itself is not indefinitely postponed.

In fact, this "natural" deflation can greatly benefit consumers, continuously improving their quality of life. Only "man-made" deflation can lead to human tragedies like the "Great Depression."

Ultimately, the deflationary trap is merely a "scare tactic." Its purpose is to provide theoretical legitimacy for the actions of artificially intervening in the value measure of money, thereby legitimizing the act of plundering the wealth of the populace through monetary means.

Conclusion

When the dust of history settles, we clearly see that the true threat to economic stability is not deflation or inflation, but the invisible hand that manipulates money. Money is the ruler of civilization, and a stable monetary measure determines the vitality of the economy and the level of social prosperity.

The emergence of Bitcoin precisely provides a value measure that cannot be arbitrarily tampered with. It gives us a currency that does not require trust in any human manipulation, a currency that can truly return to the essence of the market.

Bitcoin is not a deflationary trap; it is a pathway to escape "man-made disasters" and a natural route to economic prosperity.

Ultimately:

Deflation is not guilty; human intervention is the culprit; value has a measure, and prosperity is enduring.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。