Similar to the development of the internet, Myanmar has skipped the credit and debit card phase, transitioning directly from cash to mobile payments.

Written by: 7k

Edited by: Fangting

A Myanmar woman carries a series of identification documents to ensure her safety and legality while residing in Thailand.

Image source: Visual Rebellion, cited by Exile Hub

Introduction

During my time in Chiang Mai's pop-up city, I met Htway, a tech consultant from Myanmar. He often wore a polo shirt tucked into his jeans, resembling a young engineering student at a university, moving between various study groups, workshops, and Demo Days, raising his hand during discussions or Q&A sessions to take the microphone: "I come from Myanmar. Because of the civil war, many of my compatriots are facing severe situations. I want to ask if this technology can help…" The atmosphere in the room often turned serious.

Since the military coup in 2021, news about Myanmar has been rare on the Chinese internet, with the only concentrated reports focusing on the electric fraud centers. Although the disappearance and rescue of actor Wang Xing in Myawaddy earlier this year once again drew internet users' attention to Myanmar, overall, the information available to people remains scarce. This prompted me to get to know Htway. After one event, Htway was talking to another Myanmar national, Kha. I learned that they had been friends for many years, completely losing contact after the coup, but unexpectedly met each other at today's event.

Kha is a cryptocurrency practitioner. In November 2024, the Ethereum developer conference Devcon will be held in Bangkok, Thailand, bringing together cryptocurrency professionals from around the world for the first time in Southeast Asia. Many of them, including Ethereum founder Vitalik, worked and lived together in Chiang Mai in a digital nomad style for a month before Devcon—this was the pop-up city event. Htway was drawn to these activities, having never previously engaged with cryptocurrency or virtual currency. He had worked at a tech consulting and project incubation company in Yangon until the military coup forced him to leave and settle in Chiang Mai. Kha, on the other hand, came specifically to attend Devcon and still works within Myanmar. Due to the military government's declaration of cryptocurrency as illegal, traveling in and out is not safe for him. However, he tries to leave Myanmar once a year to connect with the outside world. Together with many similar Myanmar nationals, they hope to find practical applications for cryptocurrency technology in the increasingly harsh living conditions at home.

While in Chiang Mai, I wrote a short article introducing the situation and demands of these Myanmar people. Soon after, I met more individuals who are trying to use technology to alleviate the humanitarian disaster caused by inflation and internet surveillance in Myanmar, exploring possibilities for unmediated international aid and refugee identification, while facing a series of real difficulties. Therefore, I hope to contribute another story about Myanmar, where the protagonists are not criminals, the military, or war (although everything is related to them), but ordinary people who hope to bring change to the current situation in their hometown.

Everything Began with the Military Coup

At 3 a.m. on February 1, 2021, Bradley was awakened by a call from a companion: "Look up in the sky!" Confused, he stood by the window, only realizing a few seconds later that this was the code indicating the coup had begun. On that day, the Myanmar Defense Forces announced the overthrow of Myanmar's first democratically elected government since independence—the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The military government was reestablished, declaring a state of emergency nationwide. This coup has nearly erased the achievements of Myanmar's openness and development over the past decade, with the humanitarian crisis and economic recession escalating, plunging the country into chaos to this day.

On the day of the coup, Bradley saw people rushing to the streets to buy rice, ATMs were inoperable due to network line cuts, and phone communications quickly went silent. In the following days, protesters faced armed suppression from the military and police. Within weeks, violence against civilians escalated, with journalists in vests becoming direct targets, private residences being raided, and by March 22, 2,682 people had been confirmed arrested, with 261 confirmed killed by the military. Protesters began using homemade weapons, resistance forces started to fight, and civil war began.

Bradley's work involved training and educating on internet usage (Internet literacy), and he collaborated with parliament and government departments, so he had heard rumors of the military planning a coup before February. "No one believed it would be real, not even people in the military." Nevertheless, he and his colleagues agreed on a code and discussed strategies for dealing with communication disruptions. In the first few days of the coup, they met in the same park to share information: where protests were happening, whether anyone had been arrested, and whether the military was firing. They had no idea that this resistance against the military government's blockade policies would last for four years.

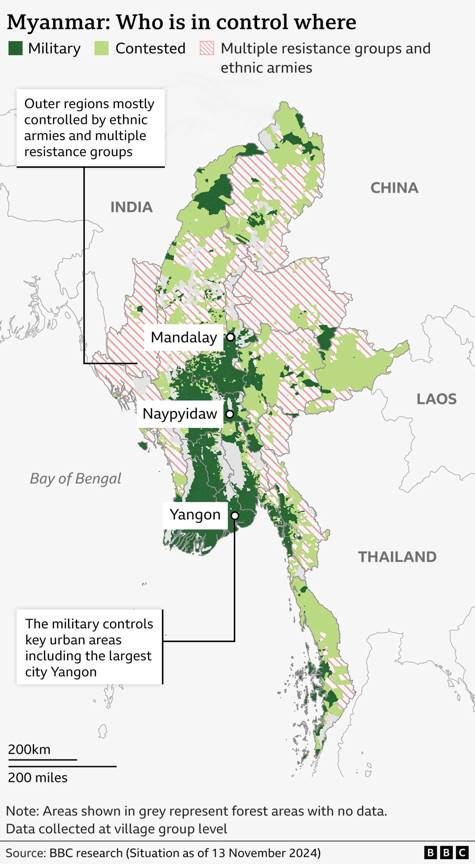

Control of the situation in Myanmar (as of December 13, 2024)

Image source: BBC

According to reports from the end of last year, ethnic armed groups and a series of resistance organizations now control 42% of the country's land. The military government still controls major cities, while most of the remaining areas are disputed, with standoffs continuing across the country. For ordinary people, even basic communication with friends and family is difficult—regarding areas they cannot control, the military implements a so-called "four-cut" policy: intercepting food, funds, information, and personnel recruitment. Internet connectivity has become very unstable due to infrastructure damage and deliberate signal jamming. Even in areas controlled by the military government, power supply shortages due to the withdrawal of foreign investment from energy and telecommunications companies have made power outages lasting half a day quite common, forcing people to adjust their work schedules daily based on power supply times.

After a colleague was arrested, Bradley fled Myanmar. In a relatively safe environment, he decided to continue tracking the internet control policies in the country with his colleagues, and they established the Myanmar Internet Project. Bradley told me that the internet blockade is not limited to signal interception; mainstream social media became difficult to access after the coup. Moreover, constant surveillance is even more dangerous: posting anti-military government comments on social media can lead to personal tracking and possible arrest; about half a year ago, internet proxy services were gradually blocked, indicating that the military government may have adopted more advanced surveillance technologies. Earlier this year, newly passed laws stipulated penalties of one to six months of imprisonment or fines for installing or providing such services, even though the military government had declared the use of internet proxies illegal as early as 2021.

Another area being monitored and cut off is payment and transfer channels: the military government has modified laws and enforced KYC (Know Your Customer) regulations, placing mobile payment accounts (such as KBZ Pay or Wave accounts) under surveillance. Suspicious accounts can be frozen without notice, and the military usually conducts raids on account registration addresses within six months. Records indicate that journalists, dissidents, or resistance organizations needing to raise funds may encounter these dangers. The depreciation of the kyat has exacerbated inflation: although the official exchange rate is forcibly maintained at 2,100 kyats to 1 dollar, the black market rate has soared to 5,000 kyats to 1 dollar, while banks have long restricted people's withdrawal limits. The military government relies on revenue from oil and gas flowing to the military rather than other essential services. Prices for essential goods like medicine are also gradually rising. Funds continue to leave Myanmar, indirectly reflected in the fact that Myanmar nationals have become the second-largest foreign buyers of Thai condominium properties after Chinese nationals.

Mobile payment wallets and bank accounts need to be linked to new electronic IDs (e-IDs) and mandatory registered SIM cards (phone numbers), and under the Anti-Terrorism Law and Cybersecurity Law, authorities can investigate and control digital platform services and electronic information, intercept, block, and restrict mobile communications, and obtain location information—except for registered SIM cards, these policy tools have been gradually implemented and passed after the coup. The identification system is an essential part of the entire surveillance chain: some people are unable to access communication and banking services due to a lack of or loss of government-issued identification—a flimsy, easily bendable paper card—while others face danger due to the ethnic, occupational, and residential information on their identification.

As Bradley told me this, we were sitting in a corridor at a Devcon side event. Behind us, guests in the conference hall were discussing a brand new social form based on cryptocurrency technology: on-chain identity, on-chain wealth, on-chain sovereignty. The world seems to be moving forward, while Myanmar is mired in an increasingly deteriorating civil war, with the military government continuously strengthening its control methods over civilians—this is a helpless, ultimate FOMO (fear of missing out). "I feel that we (Myanmar people and the global crypto community) are spiritually aligned, but perhaps not in practical applications," Bradley laughed, "at least when I discuss these with this friend, our conversations always end with: 'We're still experiencing power outages.'"

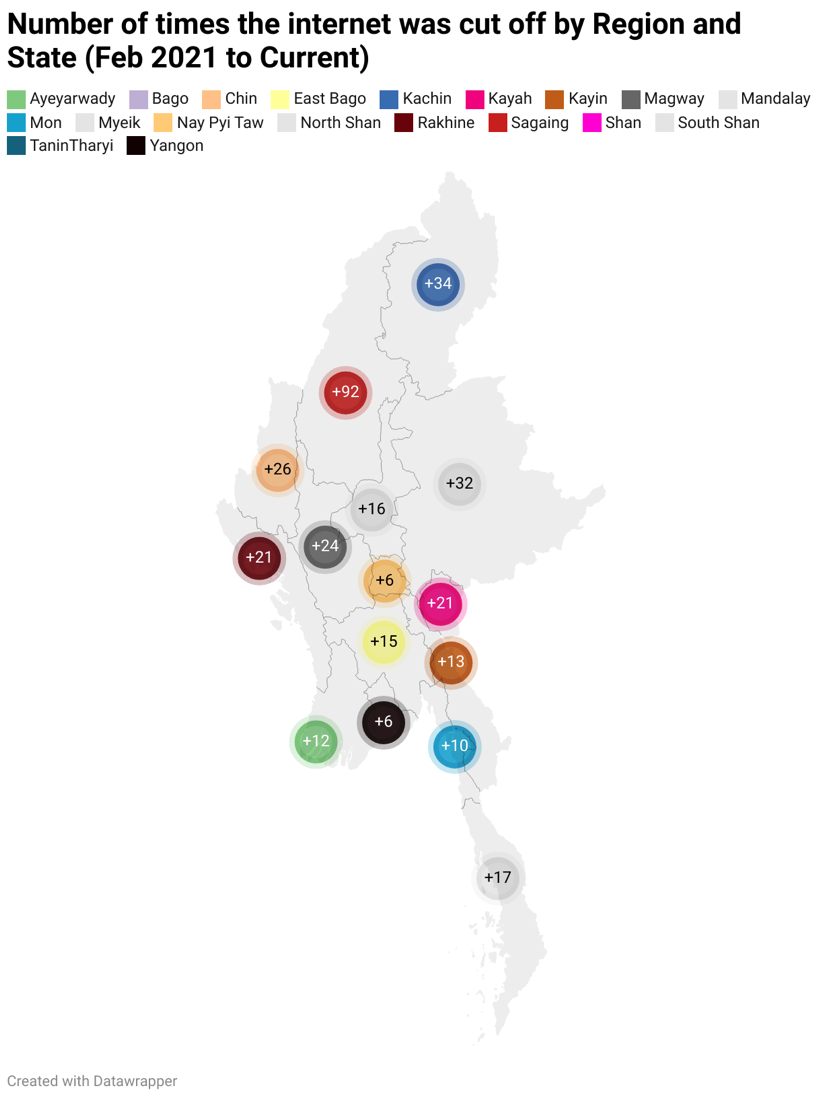

The Internet History of Myanmar

In the vast narratives of disaster, people may begin to forget Myanmar from the last decade: since the democratic reform process began at the end of 2010, internet blockades were lifted, the telecommunications industry was liberalized, and Myanmar leaped from a country with a lower mobile phone ownership rate than North Korea to one of the developing countries with the highest rates of mobile internet and smartphone usage: the price of SIM cards dropped from $2,000 to $1.50, and smartphones could be bought for about $20; Norwegian company Telenor and Qatar-based Ooredoo became licensed telecommunications service providers, breaking the monopoly of the state-owned MPT (Myanmar Posts and Telecommunications); thousands of mobile signal towers sprang up from forests and remote rice fields; in just six years, almost everyone had access to mobile internet. Since most people had no prior knowledge of the internet, ordinary individuals equated Gmail with email and Facebook with the internet itself.

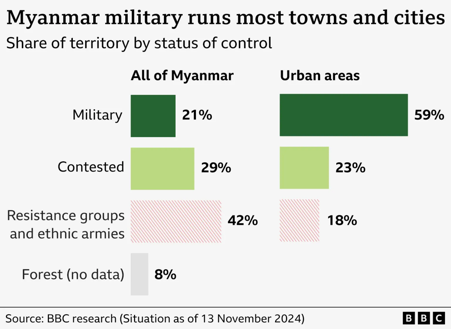

Mobile phone usage rates in Myanmar before and after telecommunications reform, nearly catching up with India, China, and the United States.

Image source: Bloomberg

At that time, Myanmar was widely seen as a brand new internet testing ground full of opportunities. Htway returned to Myanmar from abroad during this period and began working at an ICT startup center in Yangon. In a public speech in 2016, he shared his confidence in the future of the internet in Myanmar: "Hacking means solving problems in innovative ways… In this sense, Myanmar has always belonged to hackers." He said, "We need to become citizens empowered by technology. We are still separated in this country by class, privilege, wealth, language, and faith… but we are all hackers making things more useful." Many developers attempted to use the internet to address the practical problems emerging from Myanmar's intense transformation.

Despite the enormous opportunities brought by internet openness, the public and the government have always been in a struggle over internet usage rights. In 2019, the NLD government implemented a large-scale internet shutdown to combat ethnic armed groups in Rakhine State, which was widely reported as the longest ongoing internet shutdown in the world, affecting about 1.4 million people—during the pandemic, the lack of internet made it difficult to convey basic medical and assistance information. Bradley and his colleagues protested this, and when they approached the authorities, the responsible official told him, "They have 2G." Even more disappointing to him was that many people did not support their protests, "Some friends told me that the people in Rakhine are terrorists, they are 'trouble-making people.'"

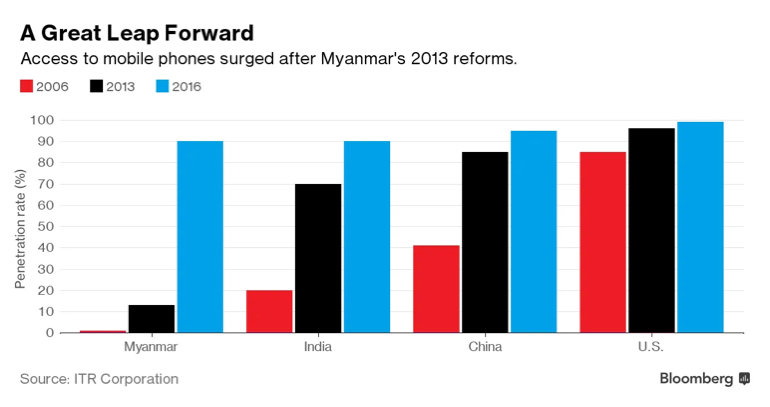

The coup caused Myanmar's internet development to stagnate once again: amid massive opposition, Telenor and Ooredoo sold their Myanmar subsidiaries in 2021 to companies with potential ties to military officials, exposing a large amount of user data to surveillance. The remaining MPT and Mytel are under the control of the military government. Resistance organizations have targeted military communications and revenue by destroying telecom towers, while the military's internet shutdown and surveillance methods have become increasingly tight. As of last July, there had been 291 internet shutdowns across Myanmar, with 80 of the 330 townships completely isolated from the outside world.

Statistics on internet shutdowns in Myanmar after the coup

Image source: Myanmar Internet Project

Under the damage to infrastructure and military blockades, people are still trying to maintain basic internet connections. Some local internet service providers (ISPs) refuse to comply with military blockade orders due to economic losses. Additionally, internet cafes equipped with Starlink (a satellite internet system operated by Elon Musk's company SpaceX) provide basic internet connectivity for many, with prices around 500-1000 kyats per hour (about 10-20 cents). The Myanmar Internet Project estimates that there are now over 3,000 Starlink antennas operating nationwide, with users including civilians, rebels, and telecom fraudsters. Insiders say that a tweet from David Eubank (a leader of a rescue organization operating on the Myanmar border) thanking Elon Musk has made more people aware of Starlink. However, since Myanmar is not on Starlink's authorized country list, SpaceX may cut off roaming services within the country, a move that has precedent in countries like South Africa and Cameroon.

Starlink internet cafe equipped with bomb shelters in Shwebo

Image source: Nyein Chan May, Myanmar Internet Project

Life as a Refugee

"Once when I returned to Myanmar to report, a bomb fell just 100 meters away from me," Mar, a Myanmar photojournalist, told me. "But no media wants photos of airstrikes anymore because they are too common." Many independent journalists have chosen to go into exile to escape targeted repression from the military, but they still frequently return to Myanmar to report. Mar's reports and photos are often sent out through Starlink internet cafes. At the time of our conversation, he had just recovered from malaria contracted in the rainforest. These journalists have produced a series of impactful works on the front lines of war or in fraud centers, winning awards at the World Press Photo competition in both 2022 and 2023. However, their current situation is a microcosm of Myanmar's exiles.

Shortly after the coup, the military government began revoking media licenses, arresting journalists, and raiding media offices. Since the coup, seven journalists and media workers have been executed, and at least 150 have been arrested and imprisoned. The revision of Law 505(a) criminalizes "spreading false information or information that may cause fear." In the 2024 World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, Myanmar is listed as one of the ten most dangerous countries for journalists globally. All of this has led to a mass exodus of journalists to neighboring countries. Mar typically travels back and forth between Myanmar and Thailand every three months because he needs to report to the immigration office regularly.

A few fortunate individuals can pay $12,000-13,000 to apply for a two-year education visa or obtain a tourist visa in other countries. Lay, a college dropout, fled to Laos to escape the military's forced conscription implemented in March 2024, and with the help of a Myanmar intermediary, he obtained a tourist visa for Thailand and is now working as a waiter for a monthly salary of $300. "That intermediary used to be a doctor, but now he makes a lot of money processing visas," Lay told me.

However, for most Myanmar journalists who come to Thailand, they usually have two options: either register as refugees, lose their passports, and be sent to countries like the United States or Australia; or pay unreasonable fees to apply for temporary work permits (pink cards). Due to the need to obtain permission from local employers, some journalists can only work as waiters or blue-collar workers. "We have an experienced journalist with 15 years of work experience who can only work as a welder now," Kyi from Exile Hub said. Exile Hub is an NGO dedicated to helping these exiled journalists and activists, providing assistance to a total of 2,100 people, including funding, short-term housing, training, and mental health counseling.

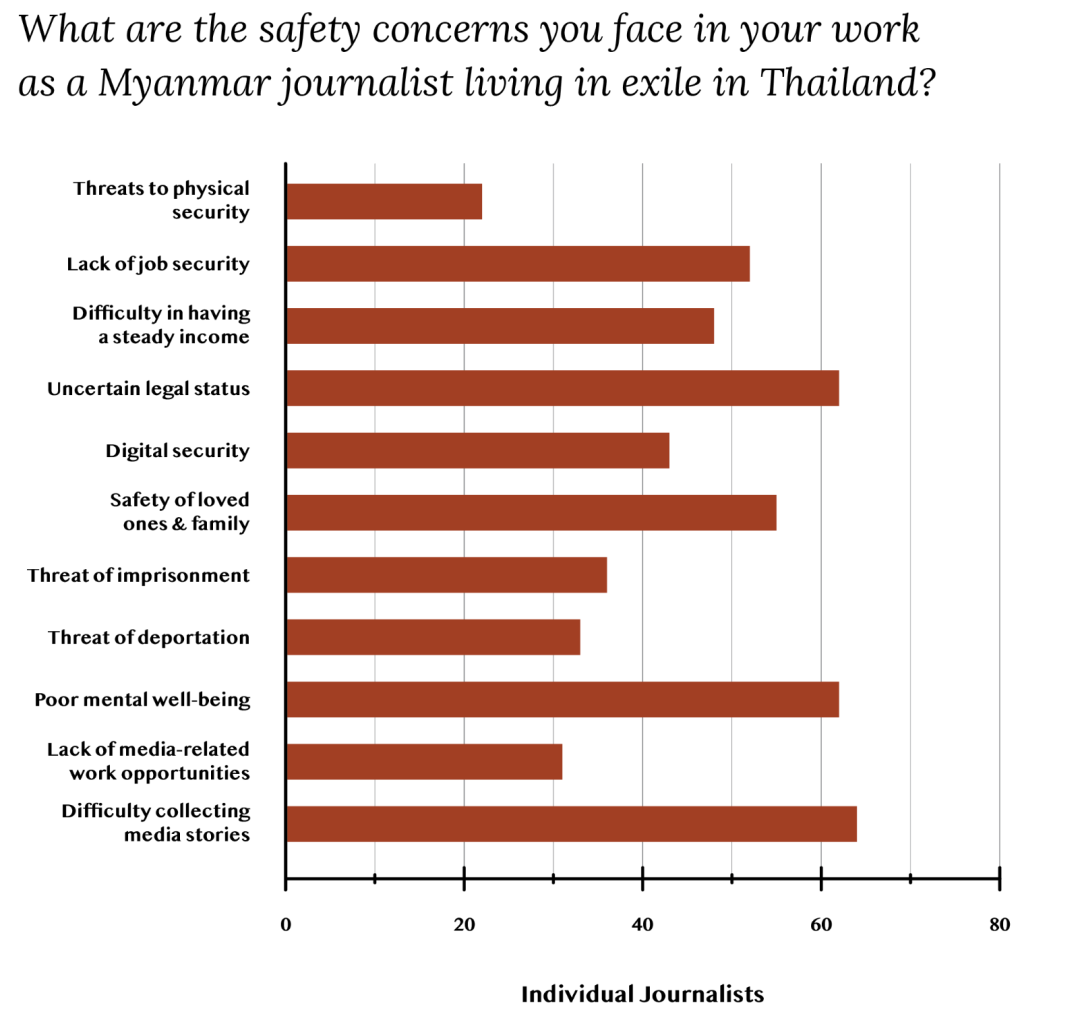

Survey: Safety concerns of exiled journalists

Image source: Exile Hub

Exile Hub also began after the coup: Kyi was a media producer in Myanmar, and after the coup, she and her colleagues began searching for channels to purchase and distribute safety helmets, journalist vests, and foreign SIM cards with data roaming. After police fired on demonstrators and targeted journalists for arrest, Kyi and her colleagues shifted to providing safety and first aid training. As more people were forced to leave Myanmar, they began fundraising to cover the costs of plane tickets, quarantine hotels, and temporary housing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the months following the coup, because there was no synchronized database between the military government's customs, immigration, and local police stations, some journalists would "take a gamble" and leave through the airport. But "Myanmar people over 30 need to update their ID cards, and many journalists have their professions listed on them, which would be the end for them," Kyi said. "Many people do not have passports, and (after the coup) they cannot apply for them. Myanmar passports need to be renewed every five years, and if your validity is within six months, you cannot travel internationally." Htway told me. Therefore, the vast majority of people must walk across the border, and exiles face the risk of arrest every time they return to Myanmar, leading to prolonged separation from family members. On top of that, the threat of deportation always looms.

In addition to the predicament regarding identification, another issue arises concerning money and its circulation channels. Many of the interviewees in this article and related reports indicate that the average salary for exiled journalists in Thailand is about $200 per month. Additionally, the existence of anti-money laundering policies makes it nearly impossible for Myanmar nationals to apply for Thai bank cards. Independent media or organizations like Exile Hub need to rely on donations and international aid to operate, but on one hand, these funds often come with conditions and must go through lengthy bureaucratic processes, rarely directly funding individual journalists; on the other hand, although many journalists are willing to forgo bylines to protect their safety, the requirements for funding assistance force them to prove their journalistic work, creating an unsolvable paradox.

"I sincerely hope someone can develop tools that fit Myanmar's application scenarios through zero-knowledge proofs (ZK) or end-to-end cryptocurrency systems, which would make my work much easier. But right now, I can't convince my funders to use these technologies because they are not operational yet," Kyi said. "It's hard to raise funds now because globally, people are less convinced of the importance of journalism… The reason people do journalism is to support the dissemination of true and accurate information and facts from Myanmar; they put their lives and their families' lives at risk not to make money. I don't want their contributions to go uncompensated."

Facilitating Money: The Hundi System and Cryptocurrency Use

In the absence of banking services and with strict controls on the flow of funds, a significant portion of currency flow in Myanmar, including international aid, relies on the "Hundi" system. This term, which has no Chinese translation, refers to an informal financial service industry originating in 12th-century India, a transfer and payment network almost purely based on trust and interpersonal relationships. "If I want to send some money to my dad, I have to find a Hundi in Chiang Mai, tell him my dad's information, and then pray that the money will get there," Htway said. "They usually manage to deliver it."

Hundi has always existed in the lives of Myanmar people, and the consensus among interviewees is that "everyone knows a Hundi." The "typical" Hundi is often a seemingly wealthy middle-aged Indian who may have other businesses, such as running a restaurant, grocery store, or purchasing agency. "But there are also many ethnic Burmese and Chinese who are Hundi. Including young people, they promote their services on Facebook, and you can also borrow money from them; they are like banks… In fact, as long as you have a foreign bank account, you can become a Hundi. They are also using cryptocurrency now," Ni, a Myanmar researcher specializing in financial consulting, told me.

Ni's main job is to help businesses and organizations transfer funds into Myanmar, so he knows many Hundi. "But the Hundi system is notoriously opaque, with service fees sometimes reaching 8%… You need to negotiate with different people, and the competition in the Hundi market is fierce," Ni shared a famous story he heard: because traditional Hundi are often reluctant to handle the extensive paperwork and terms of NGOs, a French Hundi took over many international organizations' transfer work and "disappeared" during a large aid transfer.

The military government has been trying to control the currency circulation system outside of banks, and engaging in Hundi (providing unauthorized financial services) or buying, selling, and exchanging cryptocurrencies is considered illegal. The opposition National Unity Government (NUG) recognized Tether (USDT) as legal tender at the end of 2021. "The military government has always tried to control the flow of money, but this control has not been very successful," Ni said. However, some people still have their bank accounts frozen for buying cryptocurrencies, "as intelligence agents pretend to be P2P traders."

About nine months ago, the Binance app and website were blocked by the military government—similar to the previous situation with Facebook, many ordinary people think Binance is cryptocurrency itself. Similar to the development of the internet, Myanmar skipped the credit and debit card phase and transitioned directly from using cash to mobile payments. The market penetration rate of mobile wallets in Myanmar reached an astonishing 80% in 2019. This background leads people like Ni to believe that cryptocurrencies can gain more popularity in Myanmar, "One of my daily tasks is to urge sponsors to use cryptocurrencies, training people to use this cheaper, more efficient, and stable payment channel… My friend is translating wallet software into Burmese."

In fact, the chaotic situation in Myanmar has given rise to many cryptocurrency-related projects and applications: in 2022, the National Unity Government (NUG) launched the Digital Myanmar Kyat (DMMK) and the payment wallet NUG Pay based on Stella. Coala Pay is another tool developed by a Myanmar team, aimed at directly delivering international aid to local organizations and facilitating daily transactions among refugees using stablecoins and a simple interface. Although unrelated to currency itself, a project called the "Rohingya Project" was briefly shared on Devon last year, aiming to use interpersonal networks to verify and grant on-chain identities to people in the Rohingya community.

Sin, a technical consultant in the cryptocurrency industry, is helping overseas companies pay the salaries of their Myanmar employees in cryptocurrency. "These companies have no other channels, so they can only use cryptocurrency," Sin said, "My clients usually have a monthly salary of around $400… Through digital currency, they can save money for the day they can leave Myanmar." He hopes not only to enable people to obtain cryptocurrencies but also to encourage them to start using them. On the other hand, some people still equate cryptocurrencies with crime and fraud, "In the early days of the coup, many people bought cryptocurrencies out of desperation; I heard that many lost a lot of money on Luna," Htway said. Additionally, the latest reports indicate that cryptocurrencies have been widely used in the telecom fraud industry along the Myanmar border.

"There are many benefits to using cryptocurrencies, but who is willing to do it? Businesses think there isn't enough profit, NUG's projects are not practical, and NGOs only use cryptocurrencies on a very small scale. They seem to not understand the potential of cryptocurrencies; (but in reality) this is not just a technical issue, but also a political and capital issue—who has the ability to implement it while also bearing the political risks?" Ni retorted.

Conclusion

February 1, 2025, marks the fourth anniversary of Myanmar's military coup. As always, the military government has extended the six-month state of emergency for the seventh time, postponing the deadline for holding elections to February 1 of next year. "The possible outcome is that people will eventually win the revolution and establish a democratic system, and we will all 'live happily ever after,'" Kyi said, "But if that doesn't happen—it's possible it won't happen—we still need better and more democratic organizations and operational methods."

Under the wounds of civil war and the military government's oppressive policies, the people of Myanmar are naturally attracted to cryptographic technology. Even though the destruction of infrastructure poses certain obstacles, there are still many application scenarios for cryptographic technology in Myanmar: lack of financial services, inflation, censorship resistance, identity or educational proof… Many of them use end-to-end encrypted communication software and are enthusiastic about the practical application of cryptographic technology, but often with a pragmatic, clear-eyed, and critical perspective from the margins.

With extremely high digital penetration rates, digital technology gives many Myanmar people an optimistic vision for the future, as Bradley said: "After all, how much worse can it get?" He recalled a friend who initially opposed his protests: after the civil war began, ethnic armed groups, including those in Rakhine State, quickly became significant forces against the military government, and that friend specifically sought out Bradley to apologize for his previous remarks. The ethnic tensions seemed to be smoothed over by a common enemy. "We will become the Wakanda of Asia," Bradley said.

During the interview, Mar shared some photos he recently took while reporting in Myanmar. I saw a makeshift village made of wood in the rainforest, where people squeezed together to sleep in bomb shelters every night. "Everything here is deteriorating, and the people there have nothing," Mar pointed to the village in the picture, but then it smoothly transitioned to a scene of him playing with a group of children using cyanotype (a simple traditional photographic technique that uses sunlight to create images). I recalled Bradley's story about "looking up at the sky": in four years of civil war, people found the coup, bombings, surveillance, signals, satellites, news, and freedom in the air, just like those children discovering sunlight on the fabric. Even if most of the time the sky is empty, it may represent another scene in people's eyes.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。