Original authors: Johnnatan Messias, Aviv Yaish, Benjamin Livshits

Original compilation: Block unicorn

Airdrops are a common strategy used by blockchain protocols to attract and expand their early user base. Typically, protocols distribute tokens to specific users as a "reward" for participating in the protocol, with the aim of fostering long-term community loyalty and sustained economic activity. Despite the widespread occurrence of airdrops, there is a lack of in-depth understanding of the key factors for successful airdrops. This article outlines the design space of airdrops and presents key outcomes for implementing effective strategies. We assess the success of six large-scale airdrops by analyzing on-chain data, finding that a significant amount of tokens are often quickly sold off by "airdrop farmers." Based on these analyses, we summarize common pitfalls and provide guidelines for improving airdrop design.

Blockchain protocols typically design reward programs to attract new users and enhance the loyalty of existing users. In recent years, tokens minted by distribution platforms, commonly referred to as "airdrops," have become widely popular. For instance, in 2023 alone, the total value of airdrop tokens received by users through various protocols reached $4.56 billion. Although airdrops are widely used in the blockchain space, our preliminary research indicates that there is no significant correlation between the popularity of airdrops and the platform's relative appeal compared to existing alternatives. Intuitively, this practice is not ideal and may lead to a loss of funds that could have been used to enhance the platform's quality of service (QoS).

While the basic concept of airdrops is relatively simple, the design space for such reward schemes is vast, and the specific implementation may vary depending on platform characteristics. For example, some airdrop mechanisms focus on "core users," distributing large rewards to them in the hope that these users will stimulate valuable economic activity and attract more users. However, this approach may pose potential issues: when tokens grant users the power to propose changes to the protocol through decentralized governance, a "one token, one vote" strategy is typically employed, and a single user may hold multiple voting tokens. This raises the risk of voting power centralization, where a few users hold the majority of decision-making power.

To understand why previous airdrops have not always achieved their intended goals and to quantify their success, we first articulate a series of reasonable expected outcomes for airdrops. Next, we review past airdrops, assess their performance, and reveal some interesting insights in the process, comparing them to the basic expectations. Specifically, we analyze data from five popular airdrops (ENS, dYdX, 1inch, Arbitrum, Uniswap) and a fake airdrop conducted by Sybil (Gemstone) farmers. Our conclusion is that a large portion of tokens (up to 95%) is quickly sold off through exchanges after the airdrop, indicating that these airdrops fail to achieve their intended purposes, with the primary beneficiaries being "airdrop farmers"—highly specialized users who employ complex strategies to increase their share of acquired tokens. Additionally, we describe common challenges faced by past airdrops. Given that the phenomenon of airdrops is relatively new, the understanding of their theory and practice is still in its early stages, and thus previous airdrops may not have fully succeeded in the long term. Finally, we propose recommendations for improving airdrop mechanisms based on our analysis, aiming to create a fairer airdrop mechanism for honest users.

Block unicorn note: The term "airdrop farmers" in this article refers to those who interact automatically through computer scripts or manually operate dozens of accounts, all defined as "airdrop farmers."

Our contributions are summarized as follows:

Arbitrum Study

We conducted a comprehensive case study of the Arbitrum airdrop by measuring elements such as trading volume, token distribution structure, and token value before and after the airdrop. We observed a significant increase in total daily fees during the airdrop event. However, the number of transactions per address on Arbitrum decreased after the airdrop. In contrast, other protocols without airdrops performed better than Arbitrum.

Quantitative Analysis

We performed a quantitative analysis of ENS, dYdX, 1inch, Arbitrum, Uniswap, and a fake airdrop named Gemstone. The results show that most of the funds obtained through these airdrops were sold on exchanges rather than used to create dapps or for user interactions on the platform. Specifically, 36.62% of ENS tokens were sold, 35.45% for dYdX, and 54.05% for 1inch. Generally, tokens were sold within an average of 1 to 2.34 transfers after receipt, with a median of 2 transfers.

Qualitative Analysis

We conducted a qualitative analysis of past airdrops and proposed guidelines for future airdrop designs to address the issues we identified. We focused on airdrop farming behavior and the distribution of governance tokens through airdrops. To address these issues, we recommend adopting alternative incentives, such as providing fee discounts for users' subsequent interactions within the blockchain protocol.

Multi-Chain Empirical Data

We collected data from two major Ethereum Rollup networks that have been less studied in the literature—Arbitrum and ZKsync Era—and also collected and labeled data from major airdrops. We plan to share our dataset and scripts in a publicly accessible repository.

Goals of Airdrops

Airdrops are a powerful tool for promoting protocols, acquiring users, attracting newcomers, and incentivizing existing users to engage with these protocols and their applications. They are widely used for these purposes, and there are many documented cases in the literature (see Table 1). Protocols can create tokens and distribute them to users through airdrops. For example, blockchain Rollup solutions like Arbitrum, Optimism, and ZKsync Era, as well as DeFi applications like Uniswap, 1inch, dYdX, and ENS, have all utilized airdrops.

Airdrops can take various forms, with single-round and multi-round distributions being the most common. In a single-round airdrop, tokens are distributed to users all at once, while multi-round airdrops distribute tokens in multiple rounds, each using different strategies. This approach can leverage insights from earlier rounds to address challenges encountered, such as mitigating potential Sybil attacks (i.e., multiple accounts controlled by a single entity) by observing past user behavior patterns. The choice between a single-round or multi-round airdrop depends on the protocol's goals and community dynamics.

Moreover, the timing of airdrops significantly impacts the number of eligible users receiving tokens. Compared to newer projects conducting airdrops early on, mature protocols that delay airdrops may have a larger user base. This difference in user base size introduces complexity when executing Sybil detection, as there are more accounts to evaluate and potentially guard against. If detection is inadequate, it may affect community satisfaction, and the protocol may inadvertently reward accounts associated with industrial farming, which the community may view negatively. To mitigate this issue, LayerZero Labs implemented a self-reporting mechanism. Under this system, Sybil attackers can choose to self-report and claim 15% of their token allocation.

Table 1 shows the start date, end date, blockchain, airdrop type, and project type for six airdrop projects.

Next, we break down the high-level goals of airdrops—initiating user communities—into several sub-goals. These sub-goals are not mutually exclusive, and there may be other worthwhile objectives; we focus on these goals because they reveal interesting issues faced by common airdrop mechanisms.

Attracting users in the short term.

Historically, airdrops have been used by emerging blockchain protocols to establish an initial user base and provide initial liquidity boosts for the underlying chain and its protocols. Particularly for decentralized platforms, as economic activity increases, they often become more attractive and valuable to users, promoting long-term engagement.

Establishing an initial user base is important, but it is not sufficient to maintain a high level of economic activity in the long term. Ideally, users should become daily active users of the platform. This can be achieved by issuing rewards that can only be used within the blockchain protocol or application, similar to airline frequent flyer points. For example, on Layer-2 blockchains, fee discounts can be offered for future transactions. Other potentially helpful measures include multi-round airdrops and rewarding users who complete specific "tasks" that allow them to gain a deeper understanding of the features offered by the protocol. For instance, Linea's airdrop tasks provided users with an opportunity to deeply experience its features and use cases.

Targeting users who create value for the platform.

Airdrops should focus on those users who can contribute the most to the long-term sustainability of the platform. In protocols that rely on users providing liquidity, this may refer to users who provide the most liquidity to lending pools and decentralized exchanges, or users who operate across multiple tokens. In Rollups, particularly valuable users may be "creators" who deploy popular and useful smart contracts or users who bridge tokens across chains to Rollups. These users provide additional use cases for the platform, thereby attracting more users.

Post-Trade Market Analysis

The motivation for the quantitative analysis in this article stems from the following observation: airdrop recipients often quickly sell their tokens and leave shortly after, which clearly contradicts the original intent of the airdrop. Analysis of airdrops for decentralized exchanges (DEX) indicates that recipients sometimes sell all their tokens shortly after receiving them. For example, after the ParaSwap airdrop, 61% of the tokens were quickly sold.

In both cases, most recipients stop using the relevant blockchain protocol within a few months. This pattern suggests that airdrops are ineffective in maintaining long-term engagement from recipients, or that there are a significant number of Sybil accounts among the recipients. Furthermore, rapid sell-offs may disrupt the market, especially if the market perceives them as a signal of declining confidence in the protocol's future prospects. Here, we analyze data related to six airdrops (see Table 1), sourced from the archived records of Ethereum, Arbitrum, and ZKsync Era nodes (for detailed information on data collection, see Appendix 0.A). To identify exchanges, we used a list of 620 exchange account addresses obtained from Dune and Etherscan.

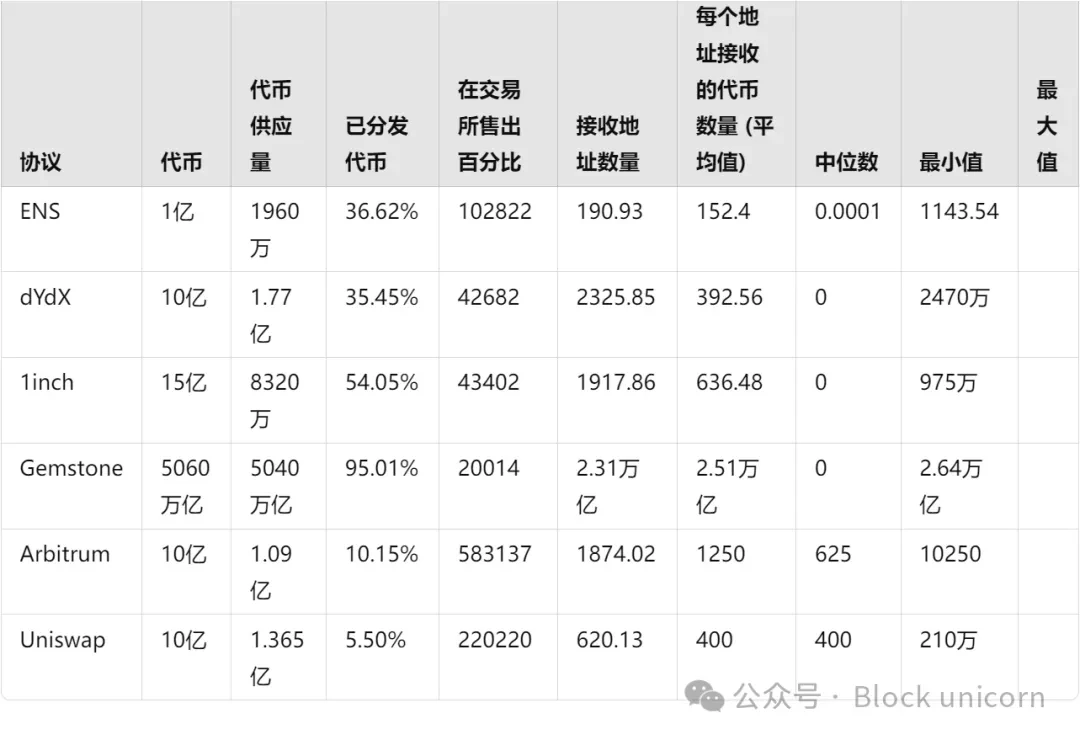

Table 2: Distribution statistics for the six airdrops. Note that protocols often send a large number of airdrop tokens to addresses they control. For details on the top beneficiaries, see Table 4 in Appendix 0.D.

Timing of Token Distribution

Table 2 provides quantitative insights into the distribution of airdrop tokens among the user base. Our analysis reveals that each airdrop has a large number of recipients, suggesting the potential presence of airdrop farmers (see column 5 of Table 2). Additionally, the data shows that tokens are frequently traded on exchanges, which is supported by the observation that recipients' first transfers after the airdrop often involve selling tokens on exchanges (see column 4 of Table 2). The Gemstone case is particularly notable, with 95% of its tokens sold on exchanges. In this Gemstone case, the airdrop was initiated by a non-open-source decentralized exchange created by airdrop farmers.

In addition, the Gemstone airdrop far exceeded other airdrops in the number of tokens distributed. This large-scale distribution also resulted in a median airdrop per recipient that was significantly higher than that of other airdrops (see Table 2). Notably, Gemstone allocated 99.53% of its total supply during its airdrop event. It is important to emphasize that Gemstone was primarily executed as a Sybil attack rather than a legitimate airdrop.

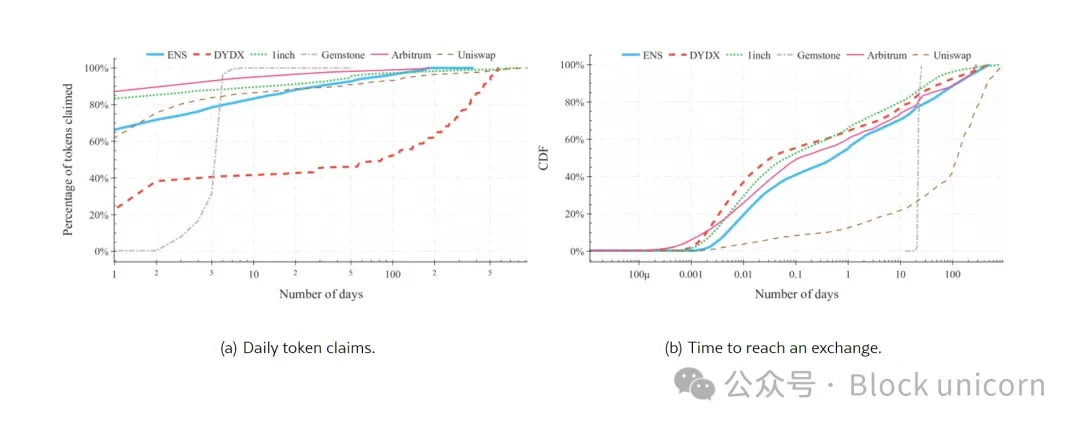

Figure 1: Comparison of token claiming and transfer patterns after the airdrop: (a) Daily token claiming; (b) Time taken to reach exchanges.

Among all the airdrops analyzed in this study, the Arbitrum airdrop exhibited the fastest token claiming speed by users. Figure 1(a) shows the distribution of accounts claiming tokens daily. Arbitrum conducted a large-scale airdrop, distributing 1,162,166,000 ARB tokens to 625,143 selected accounts. Of these, 583,137 accounts (93.28%) successfully claimed 94.03% of the ARB allocation. Remarkably, 72.45% of accounts completed their token claims on the first day, with an additional 14.41% completing them on the second day. Cumulatively, nearly 87% of accounts claimed Arbitrum's tokens within the first day of the airdrop announcement, indicating that most participants were highly engaged and acted quickly.

Table 3. With the exception of Gemstone and 1inch, the median was 1 transfer to the exchange, while other protocols showed a median of 2 transfers connecting airdrop recipients to exchanges.

Users typically interact with exchanges to swap one token for another or to sell them. To assess the frequency with which airdrop recipients profit by selling these tokens through exchanges after receiving them, we analyzed user interactions with exchanges post-airdrop. Table 3 shows that the majority of airdrop recipients traded with exchanges, with this proportion ranging from a low of 83.79% for ENS to a high of 99.93% for Gemstone.

Additionally, Table 3 displays the shortest path from each airdrop recipient address to any exchange address in our dataset. Our research found that token transfers to exchanges typically involved only a few steps, indicating that airdrop recipients did not make significant efforts to conceal their activities. Gemstone is a notable exception, as all tokens were sold in a single transfer. Surprisingly, most accounts reached exchanges through relatively few intermediary steps (usually 2 transfers). This observation underscores the critical role exchanges play in the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

Most accounts exchanged their tokens within approximately one million blocks after the airdrop. Due to delays introduced by developers, the number of blocks for Gemstone was significantly higher than for other projects. Given the different block generation times for Ethereum (one new block every 15 seconds) and ZKsync, we standardized block time to days. From Figure 1(b), it can be seen that within one day, 66.09% of 1inch accounts interacted with exchanges. In contrast, the interaction rate for ENS was 55.15%, dYdX was 64.26%, and Arbitrum and Uniswap were 60.34% and 12.39%, respectively. This rapid trading behavior contradicts one of the main goals of conducting airdrops, which is to promote sustained user engagement; the quick exchange of tokens suggests that users may leave the protocol shortly after receiving the airdrop.

Token Distribution Graph

To better understand the transfer structure that occurs after each address receives airdrop tokens, we analyzed the transfer network. Represented as G(V, E), where each node (V) represents an address, and an edge (E) is established when tokens are transferred from one address to another. Specifically, the ENS network contains 184,585 nodes and 608,462 edges, the dYdX network contains 112,853 nodes and 406,027 edges, the Gemstone network contains 20,014 nodes and 240,113 edges, and the 1inch network contains 308,329 nodes and 1,400,913 edges. Arbitrum contains 2,025,898 nodes and 27,438,608 edges, while Uniswap's network includes 1,180,830 user addresses and 3,762,613 token transfer records.

To make these graphs easier to visualize, we limited the number of hops in the data to one transfer from any address that received the protocol airdrop and plotted their largest components within the initial few hours after the airdrop, with results shown in Figure 7 in Appendix 0.B. We manually labeled high in-degree nodes using tags provided by Etherscan, a popular blockchain explorer. The results show that, except for Gemstone, the decentralized exchange receiving the most transfers (measured by in-degree) across all protocols was Uniswap, followed by SushiSwap.

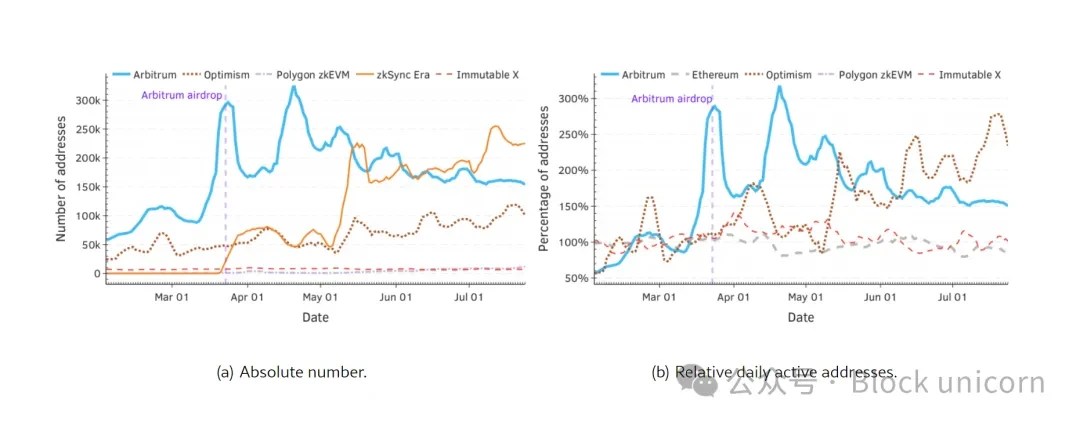

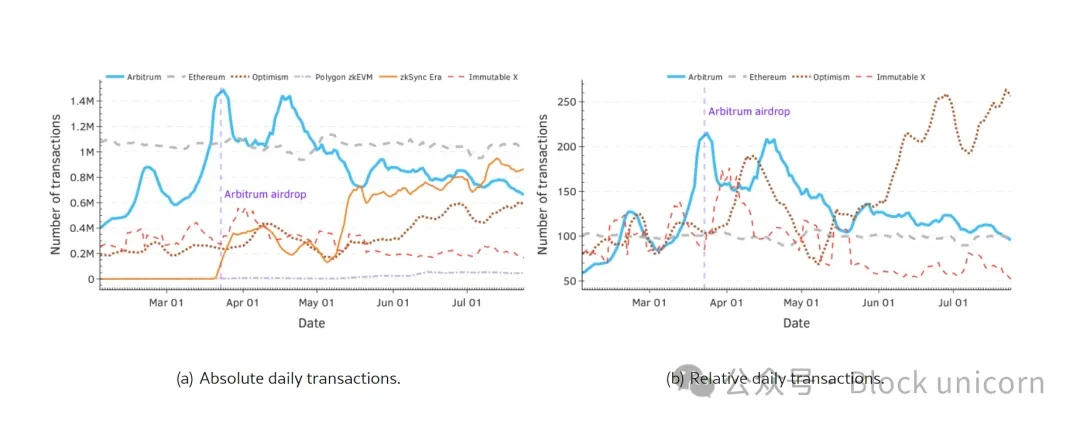

Figure 2: Daily active addresses for each protocol, (a) directly shows how many different users each platform has daily; (b) compares the daily active user count for each platform with the average before the Arbitrum airdrop, providing a clearer view of the impact of airdrop activities on user activity.

For Gemstone, all tokens were sent to address 0x7aa⋯49ad in a single transfer. On the other hand, the dYdX airdrop utilized a more diverse set of exchange addresses. Notably, as shown in Table 3, some airdrop recipients chose to sell their tokens on exchanges. We observed several common exchanges, such as Uniswap, Wintermute, and SushiSwap.

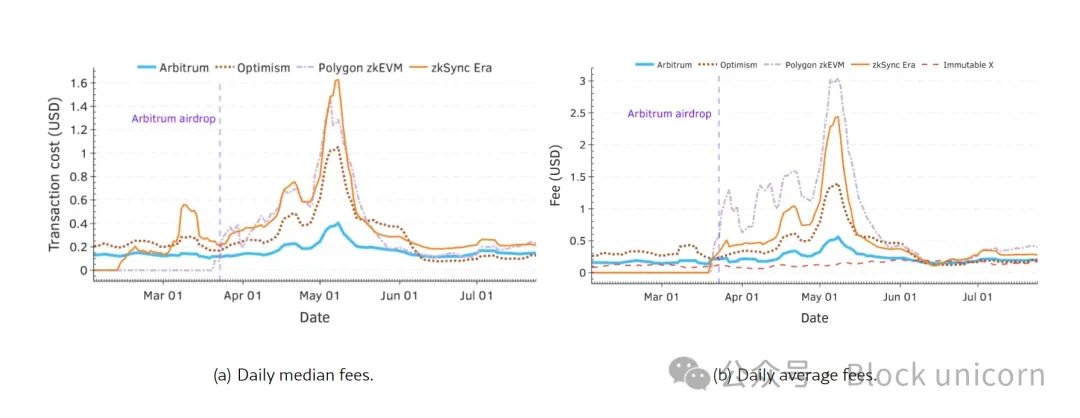

Figure 3: Daily trading fees (in USD), (a) average fee per transaction.

Measuring Airdrop Impact

Empirical research indicates that some airdrops can successfully attract users in the short term, at least on the surface. While there is some preliminary data suggesting that airdrops perform poorly in achieving other goals, substantial research on this topic remains lacking. In this section, we examine the performance of the Arbitrum airdrop through several relevant metrics (such as daily trading volume, daily active address count, median transaction fees, total value locked (TVL), fees paid by users, and stablecoin market capitalization). The data we rely on comes from Growthepie. For more detailed information on this data, please refer to the appendix.

Unique Active Addresses

Many protocols perform better without airdrops, although Arbitrum saw an increase in unique addresses post-airdrop, maintaining over 50% of its pre-airdrop level, other protocols also achieved similar growth without airdrops. For example, Optimism experienced greater address growth in May 2023, likely related to the launch of Bedrock. Similarly, ZKsync Era surpassed Arbitrum in address count within two months post-airdrop.

Fees may explain the narrowing gap between Arbitrum and Optimism. Arbitrum consistently led in daily active address counts compared to Optimism. However, data shows that this gap is closing. Before the airdrop, the number of active addresses on Arbitrum was 2.6 times that of Optimism, but over the past 50 days, this ratio has decreased to 1.83 times. The lower median transaction fees on Optimism since June may partially explain this trend (see Figure 3(a)).

The number of unique addresses fluctuates over time. The count of unique addresses exhibits volatile behavior, rising rapidly, peaking, and then declining. Notably, Optimism and Arbitrum show opposite phases in relative address counts, which may be due to users switching between protocols when fees rise. However, no such pattern is observed in median transaction fees, as Arbitrum's fees remained lower throughout mid-May 2023. Nevertheless, the unique address count may be manipulated. According to our analysis, the Arbitrum airdrop did not lead to long-term user engagement, as the unique address metric is susceptible to manipulation. Users can create multiple addresses to exploit airdrop restrictions. This makes the metric unreliable for measuring genuine activity, as significant fluctuations may stem from such behavior. Additionally, the accessibility of airdrop software facilitates the automated execution of such activities. Therefore, alternative, more Sybil-resistant metrics should be considered to assess genuine user engagement, such as combining graph network analysis with machine learning techniques.

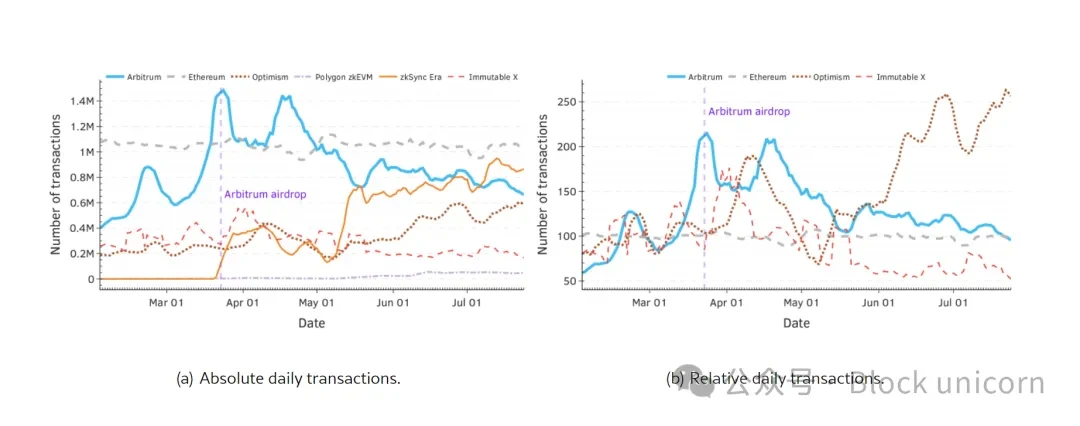

Transaction-Related Metrics

Transaction-related metrics provide a useful alternative for measuring "real" economic activity, as users must pay fees to send transactions, excluding scenarios involving retroactive rebates or protocols operating at a loss.

Considering transactions, the gap between Arbitrum and Optimism narrows. Notably, by the end of July, the difference in transaction counts between Arbitrum and Optimism had nearly closed. Additionally, the daily transaction count for Immutable X has nearly halved since the Arbitrum airdrop, while its unique address count has remained relatively stable (see Figure 4(b)). This indicates that, despite a stable address count, user engagement with Immutable X has declined.

Figure 4: (a) Directly shows the number of transactions per platform daily; (b) compares the daily transaction counts for each platform with the average before the Arbitrum airdrop, providing a clearer view of the impact of airdrop activities on transaction volume.

The transaction volume per address on Arbitrum decreased post-airdrop. To assess the impact of the Arbitrum airdrop on user engagement in other protocols, Figure 5(a) shows the relative average daily transaction volume per unique address. Since the airdrop, Arbitrum's per-user transaction volume has fallen below 75% of its pre-airdrop level. However, transaction volume without considering fees may be misleading, so relying solely on high transaction volume does not necessarily reflect genuine user engagement. In this regard, some protocols require users to conduct multiple transactions to receive an airdrop, leading to inflated activity levels when fees are low. This aligns with Goodhart's Law, which states, "When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure."

Figure 5: (a) Daily transaction counts; (b) Average daily transaction fees

Since June, the average transaction fees across all protocols have been similar. Good metrics should reflect user commitment, and transaction fees can serve as a proxy, as they measure the amount users are willing to pay to interact with the protocol. Since June, the average fees per transaction and per unique address have been similar across protocols. Comparing average fees with median fees (see Figure 3) shows that median fees may be more helpful in understanding changes in user behavior. Another useful metric is the relative average fees per address compared to the 50 days before the Arbitrum airdrop, as shown in Figure 5(b). This indicates that user engagement on Arbitrum was not significantly affected by the airdrop, generally following a pattern similar to other protocols.

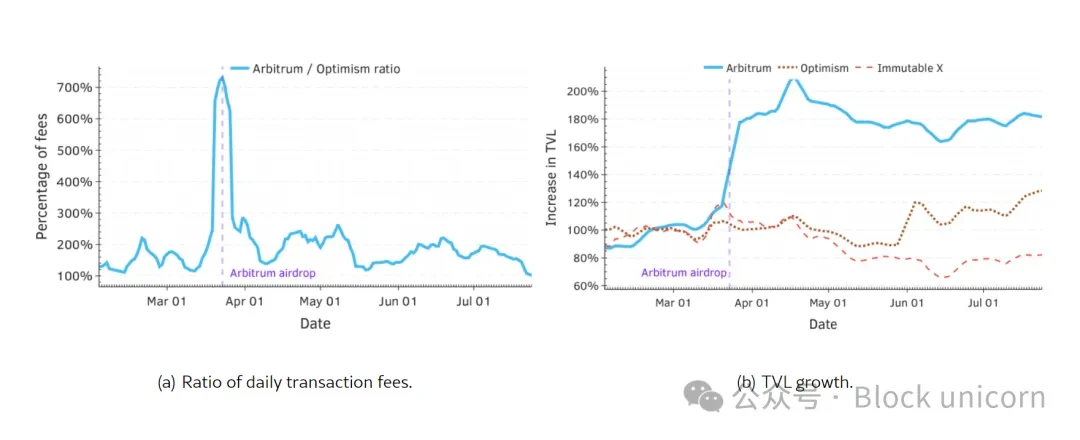

Arbitrum's total daily fees surged during the airdrop, but the airdrop did not provide it with a significant long-term advantage in terms of transaction fees, as shown in Figure 9. Although Arbitrum experienced a peak in fees on the day of the airdrop, this increase was short-lived. In fact, as seen in Figure 6(a), during the 50 days prior to the airdrop, Arbitrum's daily transaction fees were on average 1.96 times higher than those of other protocols, while in the last 50 days of the dataset, this ratio decreased to 1.74.

Figure 6: (a) Daily transaction fee ratio of Arbitrum to Optimism; (b) TVL growth relative to the average of the 50 days before the Arbitrum airdrop.

Total Value Locked (TVL) is a metric that measures the total value of all assets stored within a protocol.

The Arbitrum airdrop had a lasting impact on its TVL; among all the metrics examined, TVL is the only one that showed persistent improvement after the airdrop: Arbitrum's TVL increased by over 50% immediately after the airdrop and has not significantly declined since, as shown in Figure 6(b). This may be surprising, as Arbitrum's airdrop distribution strategy only considered user activity prior to February 6, 2023.

Common Airdrop Design Challenges

Airdrops face several common design challenges similar to traditional loyalty programs—such as new customer bonuses offered by banks and credit card companies. However, the unique context of blockchain technology and the specific mechanisms employed by most airdrops may exacerbate these challenges or even introduce new ones. In this section, we explore three of these challenges.

Airdrop Farmers

These are users who employ complex strategies to maximize the number of airdrop tokens they receive. Blockchain protocols have taken various measures to mitigate the manipulation of the system by airdrop farmers, a common approach being to limit the amount of rewards a single user can receive.

As a result, protocols have turned to Proof of Humanity (PoH) services, such as Gitcoin Passport. These services typically assign a numerical score to users based on certain metrics, with higher scores indicating a greater likelihood that the user is a real person. The metrics for Gitcoin Passport are based on a series of tasks, such as linking users' social media accounts or holding a certain amount of ETH. These methods can be enhanced by analyzing on-chain data to detect and exclude Sybil attackers, but this may lead to false negatives.

Other mitigation techniques include requiring users to perform tasks, ranging from sending a certain type of transaction to sharing posts on social media. These tasks can sometimes seem arbitrary, leading to user frustration, and are susceptible to automation and cheap deception, especially when protocols offer transaction fee rebates. Additionally, many protocols' reliance on a limited number of PoH services means that an airdrop farmer's single investment could yield substantial profits from multiple airdrops, making complete Sybil resistance impossible even with biometric verification.

Another approach adopted by protocols is to announce airdrops and retroactively reward users who were active before the announcement. However, farmers can prepare in advance and interact with these protocols even without a formal announcement of the airdrop, as demonstrated by the dYdX airdrop.

The phenomenon of reward farming is not limited to crypto-related airdrops; similar phenomena occur in "traditional" loyalty programs. In particular, the practice of credit card farming, where users apply for credit cards solely to obtain new user bonuses and then cancel the cards after receiving the rewards, is prevalent. Given that similar issues exist even in traditional environments, where users can be easily identified and penalized, the problem of rewarding airdrop users does not seem easy to resolve.

Threats to Decentralized Governance

Some protocols distribute governance tokens through airdrops to decentralize their governance processes. However, distributing governance tokens can pose risks. These tokens enable holders to participate in the governance of the protocol and make key decisions through voting. Typically, these tokens can also be exchanged for other tokens, potentially giving them monetary value, which may attract more farmers to acquire these tokens.

Empirical evidence suggests that the effects of airdropped governance tokens may outperform those of non-governance tokens. Recent analyses show that airdropped governance tokens have a market cap growth rate that is up to 14.99% higher than that of non-airdropped governance tokens. However, the authors also note that this effect is not statistically significant when using common benchmarks.

Despite these potential benefits, if not handled properly, airdropped governance tokens can pose significant risks. They may concentrate too much power in the hands of a few users, leading to an unfair distribution of decision-making power within the system. Additionally, some recipients may not consider the best interests of the protocol and may vote to change the protocol for their own benefit, potentially harming the long-term success of the protocol.

Insider Trading

This issue arises when individuals exploit privileged information for economic gain, to the detriment of other protocol users. This practice is widely regarded as a violation of securities laws in traditional financial markets and often triggers negative reactions within the blockchain community.

When someone within the protocol uses privileged information to increase their profits, it can provoke community backlash. Insiders may have advance knowledge of the metrics used to determine eligibility and rewards for each address and may exploit this information. For example, it was claimed that the growth lead of AltLayer may have profited $200,000 from insider information regarding the airdrop, but this was later deemed coincidental. However, such incidents can undermine user trust in these protocols.

This issue also raises concerns about fairness, as certain users may possess superior and more accurate information than others. Identifying these insider traders is a challenging task, so protocols need to provide detailed information to their users. Additionally, incentivizing blockchain data analysis firms and research groups to conduct post-airdrop data audits can help identify insider traders by analyzing address details and transfer patterns. To achieve this, data availability is crucial. Therefore, protocols should ensure transparency and encourage in-depth analysis to maintain the integrity and fairness of the blockchain community.

Design Guidelines

While the aforementioned design challenges are concerning, they can provide insights for future airdrop designers and guide potential paths to success.

Alternative Incentives to Maintain User Engagement

The long-term benefits of airdrops to protocols may be difficult to quantify, as potential advantages may be indirect and hard to measure, while costs are often immediate and irreversible. Additionally, certain costs and impacts, such as those arising from distributing governance tokens, may be unpredictable. Therefore, communities may consider adopting other measures to achieve a more predictable relationship between costs and benefits, rather than relying on airdrops. A simple alternative could be community voting to programmatically reward loyal users with discounts for future interactions. In the context of Layer 2 (L2) solutions, these discounts could apply to transaction fees. This approach encourages users to interact with the protocol again to benefit from the incentives, thereby promoting sustained user engagement. Furthermore, this incentive mechanism is relatively resistant to airdrop farmers, as discounts have no intrinsic value outside the protocol, and the costs are only borne by users actively using the system.

However, the design of the discount mechanism must be approached with caution, including determining eligibility criteria for users and setting appropriate discount levels. Additionally, it remains unclear whether discounts can effectively attract users as instant and tangible rewards, as airdrops do. Another option is to conduct multiple airdrops over a longer period rather than a one-time event. Although this method may still face some pitfalls associated with standard one-time airdrops, it can help ensure long-term community engagement and prevent some protocols from experiencing a drop in user adoption immediately after an airdrop. Blast has taken a more innovative approach by launching a points-based rewards program. Under this program, users accumulate points through various activities to earn rewards, such as bridging tokens to the protocol (i.e., transferring funds from another protocol) and participating in referral programs that increase user points. Notably, Blast received $1.1 billion in deposits even before its official launch. This method provides measurable metrics for users' contributions to the protocol, structured around a referral program model.

Additionally, innovative distribution mechanisms play a crucial role in mitigating the presence of Sybil attacks in whitelisted addresses. For example, Celestia proposed a unique design that uses GitHub submissions as a proxy for assessing users' contributions to the blockchain ecosystem. However, a potential concern is that users or farmers may generate false activity on GitHub to exploit airdrops from other protocols, adopting strategies similar to those of Celestia. Therefore, farmers may anticipate that new protocols will use selection criteria similar to past airdrops. To address this, protocols can focus on metrics that resist programmable manipulation, thereby increasing the difficulty or cost of creating automated user accounts.

Targeting Known Reputable Entities

Protocols can target developers and projects that are building relevant applications rather than rewarding anonymous users. For instance, in Arbitrum's airdrop, 1.13% of the distributed tokens were allocated to DAO projects. Arbitrum also provided additional incentives beyond airdrops for specific groups, such as university students and tech community members who wish to participate in research and develop tools related to the protocol.

Optimism implemented another approach by allocating a portion of its revenue for retrospective funding to successful projects, essentially introducing the concept of entrepreneurship into the blockchain world. Prioritizing established and reputable entities, including projects built on the protocol, research groups, tech communities, and students, can foster sustained engagement. By funding these entities, protocols may attract value-driven users and promote long-term participation.

Proactive Oversight and Community Engagement

During the airdrop process, continuous monitoring and analysis of protocol data are crucial to prevent malicious exploitation. For example, the Linea team discovered a vulnerability that allowed users to manipulate incentive mechanisms. Timely detection prevented cheaters from claiming more than one-third of the non-fungible tokens (NFTs) offered as incentives.

In addition to technical oversight, protocols should encourage the disclosure of vulnerabilities by maintaining open communication channels and offering bug bounties, regardless of whether the vulnerabilities have been exploited. For example, a community member of AzukiDAO disclosed a vulnerability that allowed the protocol to respond quickly. Oversight should also extend beyond on-chain data. For instance, social media is often exploited by scammers who promote fake airdrops to lure users into connecting their wallets to fraudulent websites, thereby stealing user funds. Even if a protocol does not plan to conduct an airdrop, it may still become a target for such scams.

Active community participation in technical discussions also helps enhance security. For example, the NFT airdrop of ZKsync Era was retrospectively analyzed by cygaar, revealing potential cost-saving improvements. Maintaining transparency and providing insights into the internal workings of the protocol helps build trust. When technical issues arise, well-informed users are more likely to respond with understanding.

Rewards Should Be Linked to Costs

The impact of Goodhart's Law is evident in many past airdrops. For example, airdrops are often actively announced to reward users for engaging in interactions to receive the airdrop (these projects are best avoided or are those called upon by KOLs to participate). However, these methods can be abused, and users may meet the requirements through meaningless fake transactions, rendering the standard unable to truly reflect users' genuine engagement.

The problem also lies in the operational metrics used to determine eligibility, which often fail to consider the actual costs users incur for each operation. For instance, when transaction volume is the primary metric, low transaction fees enable airdrop farmers to meet volume requirements at minimal cost. A potential solution is to adopt a reputation-based mechanism, which could curb artificial inflation of transaction volume. However, protocols must carefully define "user reputation" and the appropriate metrics for assessment.

Conversely, high transaction fees may diminish the value of the rewards users receive, reducing the attractiveness of the airdrop. To address these issues, rewards should be adjusted based on the actual costs incurred by users to ensure a fairer and more effective distribution of incentives.

Related Work

Recent research on airdrops has primarily focused on post-event analysis and guidelines for designing effective airdrop campaigns.

Airdrop Research: Yaish and Livshits proposed a theoretical model of airdrops that considers two groups: honest users and "airdrop farmers," the latter having lower costs for airdrop eligibility and deriving lower intrinsic utility from using the platform issuing the airdrop. Their analysis shows that when issuers pay a non-zero fixed cost for each recipient, the threat posed by farmers' false identities can lead to infinite issuance costs. However, they also noted that by pre-setting the total amount of airdrop tokens and distributing them evenly among all recipients, losses from farmers can be limited. Furthermore, by correctly designing the airdrop mechanism, farmers can be leveraged to promote network effects, attracting honest users who might otherwise choose competing platforms.

Makridis et al. explored the impact of governance token airdrops on the growth of decentralized exchanges (DEXs). By analyzing 51 exchanges, they found that such airdrops significantly increased market capitalization and trading volume. Lommers et al. provided a comprehensive overview of various types of airdrops (such as basic airdrops, holding airdrops, and value-based airdrop models). Their research highlighted how eligibility criteria, signaling, and implementation strategies affect the success of airdrop campaigns and offered practical recommendations for optimization. Fan et al. conducted a case study on the ParaSwap decentralized exchange, proposing a role classification based on user behavior and airdrop effects. Their research indicated that users receiving higher rewards were more likely to contribute positively to the community. Additionally, they identified arbitrage patterns and pointed out the limitations of current methods for detecting airdrop hunters. On the other hand, graph network analysis and machine learning methods were proposed as Sybil attack detection techniques to address these issues.

Allen conducted nine case studies on airdrops (such as Optimism, Arbitrum, and Blur) and provided insights into task-driven claim designs. The study emphasized the necessity of dynamic design and feedback loops, noting that due to the complexity and costs of advanced mechanisms, some projects might revert to simpler designs. Allen et al. examined the motivations behind token airdrops, particularly focusing on their roles in marketing and decentralization. Although airdrops are often viewed as marketing tools, the authors argued that this rationale is weak, as evidence of success driven by marketing is limited. Instead, decentralization and community building were emphasized as the primary motivations for airdrops.

Technical Aspects of Airdrops: Frowis et al. identified the operational challenges and costs associated with large-scale airdrops on Ethereum. They suggested that optimization through specific smart contracts could save up to 50% in costs, while extraction-based methods could shift costs to recipients. However, overall costs still remain proportional to the number of recipients.

Wahby et al. addressed privacy issues in current airdrop mechanisms, which leak recipients' information. They proposed a private airdrop scheme based on zero-knowledge proofs, using RSA credentials to achieve privacy protection while maintaining computational efficiency. Their implementation significantly improved the speed of signature generation and verification.

Conclusion

This study identified common issues in airdrops and proposed guidelines for improving their effectiveness. Our analysis of six major airdrop projects revealed a widespread tendency for recipients to quickly sell their tokens—ENS, dYdX, and 1inch tokens were traded shortly after distribution at rates of 36.62%, 35.45%, and 54.05%, respectively, with a median of only two transactions. This indicates that airdrops have failed to maintain long-term user engagement and attract valuable contributors.

For Arbitrum, we observed a surge in daily fees during the airdrop period, but this was followed by a decline in transaction volume per address. Other protocols that did not conduct airdrops performed better than Arbitrum, and since June 2023, transaction fees across protocols have tended to converge, indicating that airdrops are not the primary driver of user growth.

Finally, we discussed challenges such as airdrop farmers, governance token distribution, and insider trading, and provided insights for future airdrop strategies.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。