The best liquidation mechanism is one that minimizes the risk of bad debt at the lowest possible cost to users. However, users subject to liquidation must incur certain costs to convince liquidators to liquidate them.

Written by: Alberto Cuesta Cañada

Translated by: Lynn, Mars Finance

DeFi lending is supported by liquidation, which often feels like a dark art. Unlike traditional finance, decentralized liquidation is frequent, immediate, and typically executed by anonymous operators.

In the early days of DeFi, liquidators made huge profits, driving innovations such as flash loans and mempool competition. Meanwhile, decentralized financial lending institutions experienced market turmoil, which could lead to the disappearance of traditional financial companies.

However, despite the large amount of funds involved and the heavy workload, information on how to establish a liquidation mechanism is fragmented and dispersed. This is a nascent field, and new lenders are trying different mechanisms to address existing or imagined problems.

In this article, we will take you from the basics to the most advanced understanding of the liquidation mechanism. We will explain the factors involved in the liquidation mechanism so that you understand existing liquidation mechanisms and even design your own.

About Liquidation

As a traditional lender, you want borrowers to repay the loans they obtained from you. If they do not, you will accumulate bad debts and may go bankrupt. One measure you can take to ensure that borrowers repay the loan is to require them to provide something of value as collateral.

This is called collateral.

If a borrower does not repay the loan, or if the lender believes the loan is unlikely to be repaid, the lender will sell the collateral and force repayment of the loan, a process known as liquidation. Traditional lenders would hire trusted parties to liquidate loans that cannot be repaid and resort to legal proceedings if necessary to avoid losses.

In decentralized finance, non-repayable loans have no legal recourse, and bad debts are irrecoverable. On the other hand, the exact value of the collateral can be known at any time. For these reasons, non-repayable loans in decentralized finance are liquidated immediately if they cannot be repaid, rather than waiting for repayment on a given date.

It is easy for people to view customers who cannot repay their loans as bad customers and rarely consider their well-being. However, lenders want to protect these customers and make the liquidation process as easy as possible, as these customers may be repeat customers.

There is also a difference in liquidation between traditional finance and decentralized finance, in that DeFi liquidators are anonymous and typically not subject to review. We will see how to formulate incentives to protect lenders from bad debts.

All liquidation processes involve a balance between incentivizing liquidators and protecting users.

Solvency

To make a loan solvent, the value of the collateral must always be higher than the value of the debt. The relative value of the two assets fluctuates with volatility, and a loan that was originally solvent may become insolvent later.

If a loan becomes insolvent, the borrower has no incentive to repay the debt because the value of the collateral they receive is lower than the value of the debt they are repaying. Capital losses for the lender can accumulate rapidly, leading to bankruptcy.

To avoid this outcome, lenders will allow the liquidation of loans that are unable to repay, selling the collateral to liquidators in exchange for repayment of the debt.

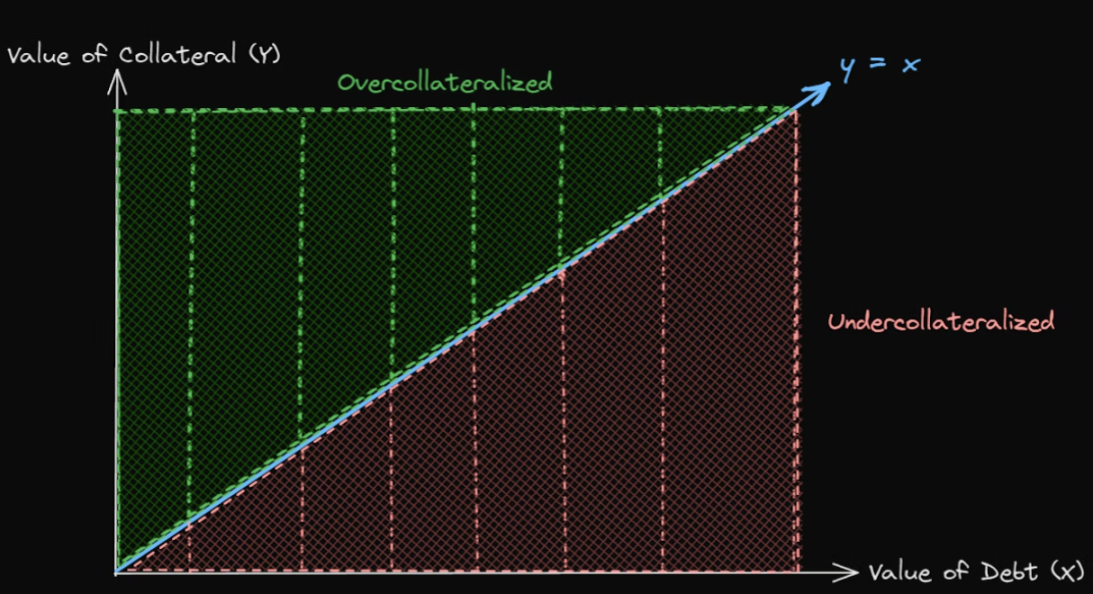

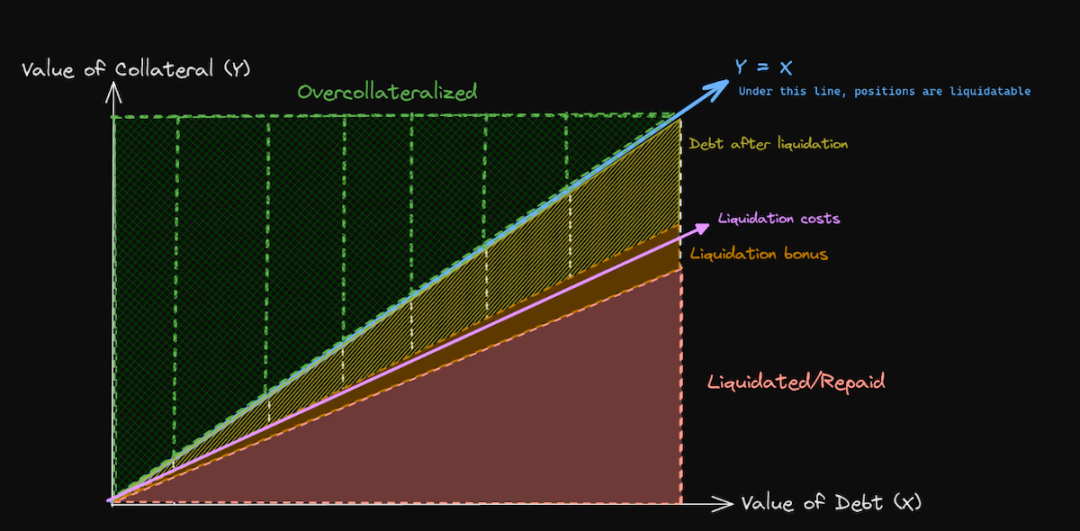

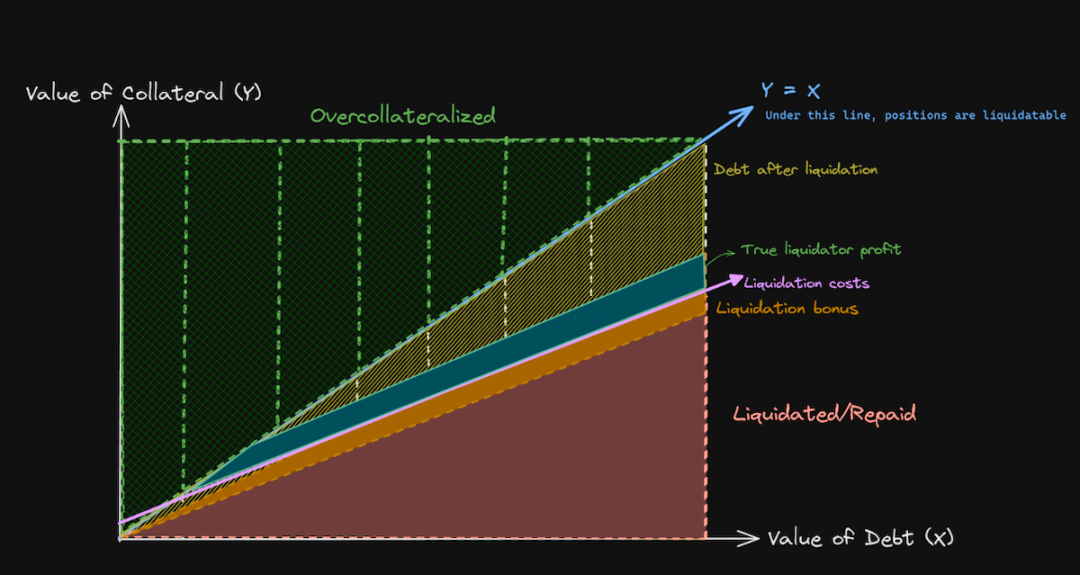

Solvency as a comparison between collateral and debt values

To maintain solvency, the basic liquidation can be implemented as follows:

- Liquidation condition: Once the solvency formula is violated, the loan is eligible for liquidation: value(collateral) == value(debt)

- Liquidation action: All collateral supporting the loan is sold in exchange for the assets needed to repay the debt.

The main drawback of the liquidation process described is that the loan can only be liquidated when the market value of the collateral is lower than the market value of the assets needed to repay the debt. This is a problem because we need to convince anonymous parties to liquidate the loan, and they will not do so without profit.

To ensure that liquidators are profitable, we need to explain the collateral ratio and make loans overcollateralized.

Collateral Ratio

The basic liquidation mechanism described in the previous section does not apply to anonymous liquidators, as they will not profit from it.

One simple way to address this issue is to liquidate the loan before it becomes unable to repay. If borrowers are required to provide more collateral than is needed to repay the debt, liquidators have time to liquidate the loan for profit when prices fall.

The collateral ratio of a loan is defined as the ratio of the value of the collateral to the value of the debt. The scenario described above is a case of overcollateralized loans, where the collateral ratio is required to be higher than 1.0.

ratio = value(collateral) / value(debt)

Taking into account the collateral ratio, we now have a different formula to determine whether a loan is healthy and eligible for liquidation. Non-performing loans still have solvency but are eligible for liquidation.

value(collateral) value(debt) * ratio

A collateral ratio exceeding 1.0 can incentivize liquidators to repay high-risk loans, protecting lenders. However, the collateral ratio is determined by the expected volatility between the debt and collateral assets. The higher the expected volatility, the higher the collateral ratio needs to be to give liquidators time to act.

For borrowers, the cost of liquidating a loan with a high collateral ratio may be very high. Therefore, this liquidation model is only implemented in conceptual verification, such as Yield v1 and the predecessor of MakerDAO, Sai.

For safety, lenders may ultimately over-incentivize liquidators. We will address this issue next.

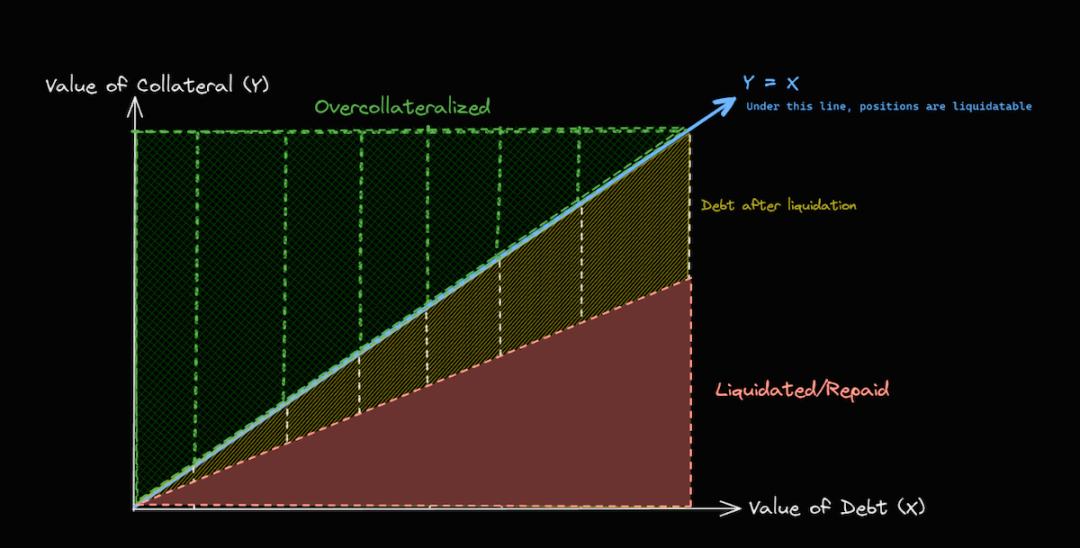

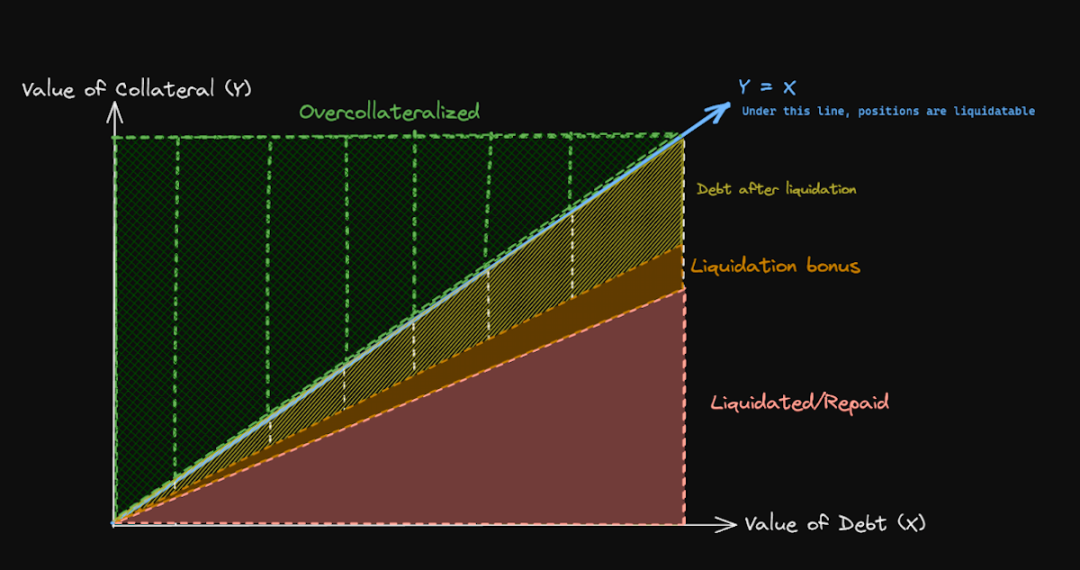

Liquidation Bonus

Now, because liquidators selfishly repay high-risk loans for personal gain, lenders can be protected from bad debts.

However, lenders need to balance their solvency and attracting borrowers. The higher the collateral ratio, the safer the lender, but users will incur higher costs during liquidation.

To manage the balance between liquidator profits, user loss magnitude, and lender solvency, a liquidation bonus has been applied since at least Compound v1. When using a liquidation bonus, liquidators typically receive additional collateral for repaying their debt at a configurable coefficient (usually far lower than the collateral ratio).

Of course, the liquidation bonus itself can be a function of any of the following:

- Total debt or repaid debt

- Collateral or total liquidation collateral

- Some other factors

Consider a loan where 150 units of collateral are used to borrow 100 units of debt, with a collateral ratio of 1.5. As the relative value of the collateral and debt decreases, a liquidator intervenes to repay 100 units of debt. Without a liquidation bonus, the liquidator would receive 150 units of collateral and could potentially make nearly 50% immediate profit.

If the liquidation bonus is 5%, the liquidator would repay 100 units of debt and receive 105 units of collateral, making a profit of up to 5%. The borrower's debt would be eliminated, and they would be able to withdraw the remaining 45 units of collateral, at most losing 5%.

When we add additional factors to the liquidation process, the risk of misconfiguration increases.

With a liquidation bonus, we need to ensure that the minimum collateral ratio is higher than the liquidation bonus. Otherwise, either the liquidation bonus will never be fully paid, or the lender will go bankrupt.

Close Factor

If the liquidation bonus is a factor of the loan size, larger borrowers will pay more during liquidation than smaller borrowers. To address this issue, lenders typically only liquidate a portion of the loan.

If a solvent but unhealthy loan is divided into two equal parts, with one part being liquidated, the borrower will receive half of the loan, plus half of the remaining collateral (not used as a liquidation bonus). This means that the remaining half of the loan has more collateral than before.

The close factor determines what proportion of the loan should be liquidated to minimize the liquidation scale while restoring the reduced loan to a healthy state. It is typically defined as a static value (e.g., 50%) in immediate liquidation mechanisms.

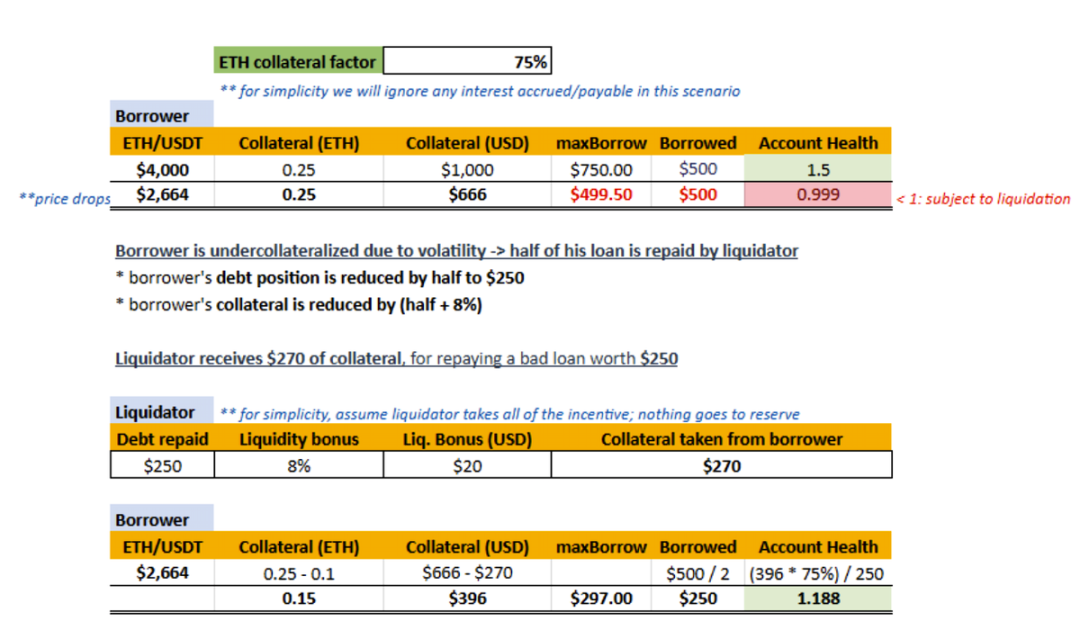

Consider an example:

- The user borrows 750 units of assets by providing collateral worth 1000 units.

- The initial collateral ratio is 1.5, reflecting the account's health status.

- The price of the collateral relative to its debt asset drops, resulting in undercollateralization.

- In this example, we assume a close factor of 50% and a liquidation bonus of 8%.

Note that in this example, the ETH collateral ratio is defined as 75% - if you deposit 1000 units of ETH, you can borrow up to 750 units of debt.

At a lower collateral price, the collateral ratio is still above 1.0, and both the user and the lender are solvent. The liquidator receives 20 units of collateral, which we hope is enough to cover their costs and make a profit.

We cannot always execute partial liquidation. In some cases, the collateral returned to the borrower may not be enough to make the remaining loan healthy. It may still be unhealthy and immediately liquidated, or it may be healthy but will soon be liquidated due to volatility. In these cases, the lender may choose to ignore the close factor and liquidate the entire loan.

Liquidation Cost

Today, liquidation is closely integrated with various market mechanisms. Liquidators typically obtain assets in the form of flash loans to repay debts, which may come at a cost. Flash loans are typically repaid by exchanging part of the collateral received at decentralized exchanges, incurring additional costs such as exchange fees and slippage. Only the remaining collateral after deducting the fees counts as profit.

Liquidators also have to pay for gas to execute liquidation transactions. Liquidations typically occur in situations of high price volatility, intense block space competition, and gas prices higher than usual.

Liquidators incur additional costs, such as developing and maintaining software that must check all new blocks on the blockchain to compete with other liquidators to liquidate loans.

Flash loans and transaction costs erode the liquidation bonus factor, while development and maintenance costs remain constant. The liquidation bonus coefficient needs to be higher than the estimated flash loan and transaction coefficients, so the larger the loan size, the higher the profit.

Please note that we assume the liquidation costs in this graph are linear - this may vary in practice.

Throttling

Another factor to consider when thinking about market mechanisms is market liquidity.

After liquidation, the collateral for the loan is typically sold immediately, unless the liquidator is keen on holding depreciating assets. However, this is unlikely. This raises concerns about the available market liquidity for such sales.

Some individuals hold more of a specific asset than their available liquidity; CRV is a recent notorious example. If loans are allowed to be collateralized with illiquid amounts, then these loans are effectively unliquidatable.

The solution is to set hard limits on the collateral allowed for each loan, so that a single liquidation will never exceed the tradable quantity of the collateral. Even if a borrower issues multiple loans with the maximum collateral, these loans will be liquidated separately, giving the market a chance to handle them one by one.

A different solution is a dynamic close factor, to liquidate large loans in smaller parts, achieving a similar effect.

These solutions are not perfect, as market liquidity cannot be consistently predicted in advance. Only integration between lenders and exchanges allows for liquidation triggered not only by price changes but also by liquidity changes.

Dust

Once we take gas costs into account, smaller loans become unprofitable, as the gas required to liquidate them is more expensive than the bonus granted by the lender.

MakerDAO introduced a dust factor, prohibiting the collateral amount for a loan from falling below the threshold expected to make the loan profitable.

This approach is problematic, as it depends on unknown and unpredictable factors such as gas prices and the value of the collateral relative to the price of Ethereum. Major lending institutions have refused to implement dust thresholds, and after years of operation, large-scale vulnerabilities remain unknown.

Given the operational expense and attack surface of implementing thresholds, we will avoid them.

Auctions

So far, we have been discussing immediate liquidations that occur in a single transaction. A loan becomes unhealthy and is liquidated at the same moment to achieve predictable profit. The profit is also proportional to the loan size.

This means that larger loans are more profitable for liquidators, but also riskier for borrowers.

Lenders do not want to penalize their largest clients, and auctions are sometimes used as a tool. When liquidating loans through auctions, the goal is to make liquidators compete and hand over the liquidation rights to the liquidator who will execute the liquidation with the least profit.

The initial implementation of liquidation auctions may have been in Sai, which used an English auction where liquidators escrow funds to repay the debt, while quoting a price equivalent to reducing the liquidation bonus over a certain period. Liquidators escrow funds, preventing them from using flash loans, making this method unusable now.

MakerDAO introduced a Dutch auction. In a Dutch auction, the bonus paid to the liquidator increases over the duration of the auction. If the liquidator waits, they have the potential to make higher profits, but also the risk of being taken advantage of by other liquidators. In a competitive environment, the result is usually that the liquidator ends the auction once they exceed their profit threshold.

If the Dutch auction is set to start with a liquidation bonus higher than 0%, the effect may be an immediate auction, followed by a gradual increase in the liquidation bonus if no liquidator is found. This is the method used in Yield v2.

For lenders implementing auction liquidations and liquidators hoping to make a profit, liquidation auctions are more complex than immediate liquidations. The benefits of dynamic debt pricing must be balanced with the increased attack surface and entry barriers for liquidators.

In any of the above cases, the additional complexity of implementing auction liquidations must be considered. In immediate liquidations, there is only one participant, the liquidator, and only one transaction, the liquidation. In auctions, we will have an auctioneer and a liquidator, who will typically submit a transaction at different times and must be rewarded for it. The attack surface is greatly increased, and the incentive program is more complex, which may not always be a more effective and reasonable balance for liquidation pricing.

Socialization of Bad Debt

Loans that cannot be liquidated are collectively referred to as bad debt. Sometimes they are combined into a single value that is easy to use, such as sin in MakerDAO.

Bad debt is dangerous because it indicates that lenders cannot fulfill all their commitments, whether it is returning the collateral entrusted to them or providing profits to users who provided liquidity. Since this may be a situation where users who abandon the lender bear all the losses, it is usually a race to exit, with catastrophic results.

Typically, this hole in the balance sheet is filled by those who manage the treasury for the lenders. However, immediately socializing bad debt among all or part of the protocol users seems like a better idea. This avoids a self-reinforcing cycle.

A Completely Different Approach

I recently read about a completely different approach taken by Instadapp in building Fluid. The code is not yet available, but it hints at integration with a DEX in the style of Uniswap v3, and their statements about liquidation allow us to infer the possible design.

In Uniswap v3, liquidity providers are equivalent to options traders within a certain price range. When the price in the trading pool crosses the range where they provided liquidity, their assets are traded. Let's extend this idea to the lending space, but with a difference.

When a borrower provides collateral, that collateral is used as liquidity in the relevant DEX, in a pool where the collateral is traded against the assets borrowed by the user. The debt is not collateralized by the collateral itself, but by the liquidity position provided.

If the value of the collateral relative to the borrowed assets decreases, the price changes through the relevant liquidity position in the DEX. The result is that the collateral is immediately exchanged for the borrowed assets at market price.

From the lender's perspective, the loan is always collateralized. From the user's perspective, the value of their collateral depends on the market, and if the market turns against them, they may receive less collateral than they deposited.

This approach requires deep integration with a DEX in the style of Uniswap v3, but it has undeniable advantages:

- There is no dedicated role for liquidators; regular activity in the DEX executes liquidations.

- Users do not pay any bonuses to liquidators, meaning their liquidation penalties are minimal.

- Market liquidity is not an issue, as borrowers provide liquidity when issuing loans.

Conclusion

Liquidation mechanisms are crucial for DeFi lending, but they are rarely understood. Users are interested in their investment returns, not the stability of lenders. No one thinks they will be liquidated, so they only care about how much they lose during liquidation.

On the other hand, the designers of lenders should be aware that improperly designed liquidation mechanisms will be a fundamental problem. Even if a complete disaster is avoided, dissatisfied liquidated users will still make their voices heard.

The best liquidation mechanism is one that minimizes the risk of bad debt at the lowest possible cost to users. However, users subject to liquidation must incur certain costs to convince liquidators to liquidate them.

In this article, we have discussed solvency and health. We have discussed collateral ratios, liquidation bonuses, close factors, liquidation costs, and market restrictions. We have discussed auctions as a way to achieve optimal liquidation. Finally, we have also hinted at market integration, which may render current liquidation mechanisms obsolete.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。