Source: SenseAI

Image source: Generated by Wujie AI

"Now I have become death, the destroyer of worlds" - this line appears twice in Nolan's movie "Oppenheimer", it is not only the most famous line in the "Bhagavad Gita", but also Oppenheimer's thought on his nuclear test. As the founder of OpenAI, Sam Altman shares the same birthday with Oppenheimer and has always been compared to the bomb maker. At the same time, he is also a practitioner of mindfulness and has known Jack Kornfield, the meditation teacher of Steve Jobs, for many years. This article details Altman's growth and development, his thoughts on mindfulness and technology, social change, and the future of OpenAI. Sam Altman says he can see our future, is he the Oppenheimer of our time?"

Sense Thinking

We attempt to propose more divergent deductions and contemplation based on the content of the article, and welcome discussions.

- A conscious digital being is a narrative subject frequently seen in science fiction. Recently, scholars from MIT have published a paper proving that LLM is not just a superficial probability model, but is capable of understanding time and space and forming a perception of the world. Regardless of how we define "understanding the world", this technological evolution led by OpenAI is more of a social revolution, affecting aspects such as politics, civil rights, economic inequality, and education.

- Altman's proposed Law of Moore for Everything states: in this world, over the past few decades, the prices of all goods such as housing, education, food, and clothing have halved every two years. The accelerated socioeconomic changes driven by technology call for corresponding adjustments in public policies. Regarding the regulation of artificial intelligence technology, due to the ambiguity of generative AI technology, it may be more appropriate to regulate within its specific scope of application, rather than establishing a regulatory body modeled after the International Atomic Energy Agency. Of course, the creators of the technology determine its direction of development.

This article has a total of 9886 words, and requires about 15 minutes for careful reading.

01. At the Mindfulness Summit

From left to right: Soren Gord Hamer (founder of Wisdom 2.0); Jack Kornfield; OpenAI CEO Sam Altman

This spring, 38-year-old OpenAI CEO Sam Altman sat with the popular Buddhist monk Jack Kornfield at the "Wisdom 2.0" forum held at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. This is an event dedicated to combining wisdom with "the great technologies of our time". On a dark mandala-backed stage, the two sat on large white cushioned chairs. Even the host seemed puzzled by Altman's presence.

He asked, "How did you get here?"

"Yes, well…" Altman said. "I'm definitely interested in this topic" - formally speaking, mindfulness and artificial intelligence. "But meeting Jack is one of the greatest pleasures of my life. I'm glad to discuss any topic with Jack."

Kornfield, 78, whose works include "The Wise Heart" and has sold over 1 million copies, made the agenda clearer as he delivered his opening remarks.

"My experience is, Sam… I want to use the language, he is a very servant leader." Kornfield witnessed Altman's outstanding character here. He will answer a question that troubles many of us: how much security should we have in Altman, as this relatively young man in charcoal Chelsea boots and a gray waffle-knit sweater seems to be controlling how artificial intelligence will enter our world?

Kornfield said he has known Altman for several years. They meditate together. They discussed a question: how does Altman "establish values - the bodhisattva vow, caring for all beings"? How can he "in some way, in the deepest way, encode compassion and care into the program"?

Throughout Kornfield's entire speech, Altman sat cross-legged, with his hands clasped together on his knees, his posture impressive, and his facial expression conveying patience firmly (although his expression also clearly indicates that patience is not his natural state). "I will embarrass you," Kornfield warned him. Then, the monk addressed the audience again: "He has a pure heart."

For most of the remaining time in the group discussion, Altman was eloquently expounding his views. He knows people are afraid of artificial intelligence, and he believes we should be afraid too. Therefore, he feels a moral responsibility to come forward and answer questions. He said, "It's very unreasonable not to do so." He believes that as a species, we need to work together to decide what artificial intelligence should and should not do.

According to Altman's own assessment - as seen from his many blog posts, podcasts, and video activities - we should be relieved but not great about him as a leader in artificial intelligence. As he understands it, he is a clever but not genius "tech bro" with the traits of Icarus and some distinctive features. First, he has "absolutely delusional self-confidence". Second, he has a long-term foresight of "the arc of technology and social change". Third, as a Jew, he is both optimistic and expects the worst. Fourth, he is good at assessing risks because his mind is not clouded by other people's ideas.

The downside is: he is not suited for this role emotionally and demographically. "He admitted in the March Lex Fridman podcast, "There might be someone who is more suited for this role." Someone who is more charismatic." He knows he is "out of touch with the reality of most people's lives". He occasionally makes startling statements. For example, like many in the tech bubble, Altman also uses the phrase "median human" - for example, "To me, AGI (artificial intelligence) is like a median human you could hire as a colleague".

At Yerba Buena, the host asked Altman: how does he intend to imbue artificial intelligence with values?

Altman said, one of his ideas is to "gather as many humans as possible" to reach a global consensus. You know: a joint decision: "These are the value systems that should be incorporated, these are the absolute restrictions that the system cannot do."

The whole room gradually quieted down.

"I want to do another thing, which is to have Jack write ten pages, saying 'Here are the collective values, here's how we make the system do this'."

The whole room became even quieter.

Altman is not sure whether the revolution he is leading will be seen as a technological revolution or a social revolution in the long river of history. He believes that it will be "bigger than a standard technological revolution". However, he also knows that he has been hanging out with technology founders since he was an adult, "saying 'this time is different' or 'you know, my stuff is super cool' is always annoying". The revolution is inevitable, and he is unwavering in this belief. At the very least, artificial intelligence will disrupt politics (deepfakes have become a major concern in the 2024 presidential election), labor (artificial intelligence has become the core of the Hollywood writers' strike), civil rights, surveillance, economic inequality, military, and education. The power of Altman, and how he will use it, is the question we are facing now.

However, it is difficult for us to discern what kind of person Altman really is; to what extent we should trust him; and to what extent he integrates the concerns of others, even as he stands on stage intending to assuage their worries. Altman said he will try to slow down the pace of the revolution as much as possible. However, he told the attendees that he believes everything will be okay. Or maybe it will be fine. The word "we" - with its royal connotations - plays a significant role in his words. We should "decide what we want, decide to execute it, and accept the fact that the future will be very different, and possibly better."

This statement was not very well received.

Altman said, "Everyone nervously laughed."

Then he waved his hand and shrugged. "I could lie to you and say, 'Oh, we can totally stop it.' But I think it's…"

02. Global Values

Altman did not complete this thought, so the reporter resumed the conversation at the OpenAI office on Bryant Street in San Francisco at the end of August. Outside, the streets were a flea market of new capitalism: self-driving cars, dogs sunbathing next to sidewalk tents, malfunctioning bus stops for the public transit system, and shops selling $6 lattes. Inside OpenAI, it was a low-key and unassuming tech company: help yourself to a Pellegrino from the mini-fridge or slap on our logo.

In person, Altman is more charming, serious, calm, and dorky - more so than imagined. He is likable. His hair is graying. He wears the same waffle-knit sweater, which quickly became his trademark. I was the 10 billionth journalist he hosted this summer. As we sat in a soundproof room, I apologized for subjecting him to another interview.

He smiled and said, "Nice to meet you."

After Kornfield's speech, someone told the reporter, "You know, I was very nervous when I came, worried that OpenAI would make decisions about the values of artificial intelligence, and you made me believe you wouldn't make those decisions. 'I thought, 'Great.' Then they said, 'No, now I'm even more nervous. You're going to let the world make these decisions, and I don't want that.'"

Even Altman himself felt a bit out of place answering questions about global values on stage. "In 2016, he told Tad Friend of The New Yorker, 'If I weren't involved, I'd say, why should these people get to decide my fate?' Seven years later, after extensive media training, his attitude has softened. "I have a lot of sympathy for government projects like OpenAI."

The new image of a good person is difficult to reconcile with Altman's will to power, which is one of his most well-known traits. A friend in his inner circle told me, "He is the most ambitious but still rational person I know in Silicon Valley, and I know 20,000 people in Silicon Valley."

Nevertheless, Altman explains his rise in a nonchalant manner. "I mean, I'm a Jewish kid from the Midwest, at best just an awkward childhood. I'm one of the few…," he mumbled to himself. "You know, the first few most important tech projects. I can't imagine something like this happening to me."

03. From Childhood to Founding OpenAI

Altman grew up in the suburbs of St. Louis, the oldest of four siblings: three boys, Sam, Max, and Jack, each two years apart, and a girl, Annie, nine years younger than Sam. If you didn't grow up in a middle-class Jewish family in the Midwest - speaking from experience - it's hard to imagine the kind of potential self-confidence such a family could instill in a son. "Jack Altman once said, 'One of the best things my parents did for me was to constantly (I think several times a day) affirm their love and believe that I could do anything. The resulting confidence is delusional, anesthetic, weapon-grade. It's like having an extra valve in your heart."

According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the story about Sam is usually like this: he was a child prodigy - "a latecomer to the tech prodigy world". He started repairing the family's VCR at the age of 3. In 1993, on Altman's 8th birthday, his parents - dermatologist Connie Gibstein and real estate broker Jerry Altman - bought him a Mac LC II. Altman described this gift as "the dividing line in my life: before and after the computer".

The Altman family had dinner together every night. At the dinner table, they would play games like "square root": someone would shout out a large number and the boys would guess. Annie would use a calculator to check who was closest. They also played the "20 questions" game to guess the surprise dessert for the night. The family also played ping pong, pool, board games, video games, and charades, and everyone knew who won. Sam enjoyed these games the most. Jack recalled his brother's attitude: "I had to win, everything was up to me." The boys also played water polo. "Jack told me, 'He would disagree, but I would say I'm better. I mean, there's no doubt I'm better.'"

Sam came out as gay in high school, which even surprised his mother, as she always thought Sam was "just that kind of androgynous tech guy". As Altman said in a 2020 podcast, the private high school he attended "was not the kind of place where you could really stand up and talk about being gay". In his senior year, the school invited a speaker for the National Coming Out Day event. A group of students expressed opposition, "mainly based on religious beliefs, but some also thought that gay people were bad." Altman decided to speak at the student council. He hardly slept the night before. He said in the podcast, the last sentence was: "Either you tolerate an open community, or you don't, you don't have the right to choose."

In 2003, as Silicon Valley was beginning to recover from the dot-com bubble, Altman entered Stanford University. That same year, Reid Hoffman co-founded LinkedIn. In 2004, Mark Zuckerberg co-founded Facebook. At that moment, the eldest son of the suburban Jewish family did not become an investment banker or a doctor. He became an entrepreneur. In his sophomore year, Altman and his boyfriend Nick Sivo started developing an early geotracking program - Loopt, for locating your friends. At the time, Paul Graham and his wife Jessica Livingston had just created the Summer Founders Program as part of their venture capital firm Y Combinator. Altman applied and won a $6,000 investment, and had the opportunity to spend a few months in Cambridge, Massachusetts with like-minded nerds. That summer, Altman worked very hard, to the point of getting sepsis.

However, at Loopt, he did not particularly stand out. Hoffman said, "Oh, another smart young person!" Hoffman, who was a member of the OpenAI board until January of this year, still remembers his impression of the young Altman. This was enough for him to secure a $5 million investment from Sequoia Capital. However, Loopt never gained favor with users. In 2012, Altman sold the company to Green Dot for $43 million. Even he himself did not consider this a success.

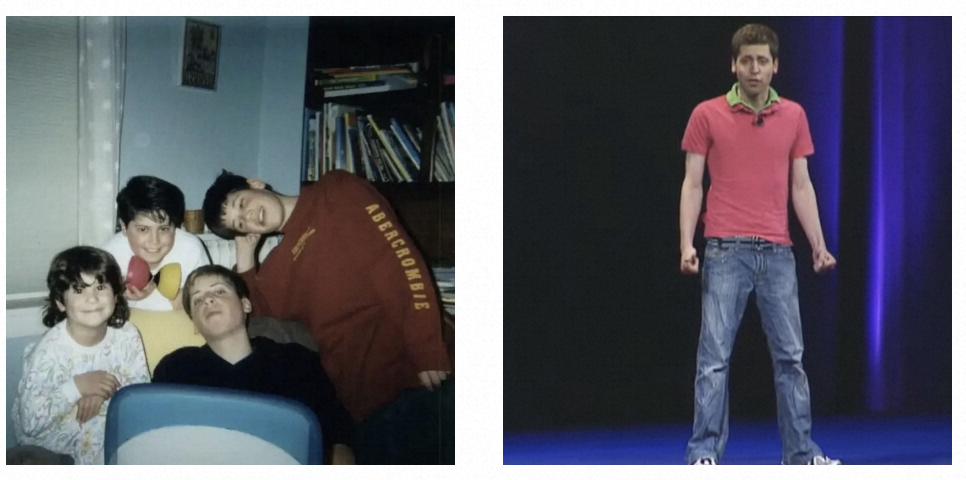

Sam Altman's growth story: Left to right: in the 2000s, with siblings at the age of 14 or 15. At 23, promoting Loopt at the 2008 Apple WWDC. Photos provided by Annie Altman; CNET/YouTube.

Altman told me: "Failure is always bad, but it's really bad when you're trying to prove something." He left the company "very unhappy," but he got $5 million, and with that money, along with Peter Thiel's support, he founded his own venture capital fund, Hydrazine Capital. He also took a year off, read a lot of books, traveled, and played video games, "like a total tech guy," he said, "I thought, I'm going to stay at the Aśvins Temple for a while, and it changed my life. I was sure I was still anxious and stressed in many ways, but I felt very relaxed, happy, and calm."

In 2014, Graham asked Altman to take over as president of Y Combinator, which had already helped found Airbnb and Stripe. In 2009, Graham described Altman as "one of the five most interesting founders in the past 30 years," and later described him as "like Bill Gates when he founded Microsoft… a natural, confident person."

During Altman's tenure as YC president, the incubator received about 40,000 applications from new startups each year. The incubator listened to in-person pitches from about 1,000 companies. Hundreds of them received funding from YC, usually around $125,000, along with guidance and a network (including weekly dinners and co-working time), in exchange for 7% of the company. Running YC could be said to be the greatest job in Silicon Valley, and also one of the worst. From the perspective of venture capitalists (some say, some of them spent a lot of time and effort), running YC could be said to be one of the greatest jobs in Silicon Valley, and also one of the worst.

For most of his time in office, Altman and his brothers lived in one of his two houses in San Francisco, one in SoMa and the other in the Mission. He preached ambition, solitude, and scale. He believed in the value of hiring from the network of acquaintances. He believed in not caring too much about what others think. "A big secret is that you can make the world bend to your will to a large extent - most people haven't even tried," he wrote on his blog. The most successful founders are not trying to start a company. Their mission is to create something closer to a religion, and sometimes starting a company is the easiest way to do that. The bigger downside is to force yourself into a corner of small ideas without enough perspective.

Altman's life has been quite eventful. He became extremely wealthy. He invested in products that boys dream of, such as developing supersonic aircraft. He bought a house in Big Sur, filled with guns and gold. He races in his McLaren.

He also adheres to a utilitarian philosophy of tech supremacy - effective altruism (EA). EA makes big money almost by any means, based on the theory that its followers know best how to spend money. This ideology sees the future as more important than the present and imagines a euphoric singularity after the fusion of humans and machines.

In 2015, within this framework, Altman, Elon Musk, and four others - Ilya Sutskever, Greg Brockman, John Schulman, and Wojciech Zaremba - co-founded the non-profit organization OpenAI. The 501(c)(3) mission is to create "a computer that can think like a human in all aspects and use it for the greatest benefit of humanity." The idea is to create good AI before bad actors create bad AI and dominate the field. OpenAI promises to open-source its research results according to the values of EA. If someone - or someone they consider "value-aligned" and "safety-conscious" - is ready to achieve AGI before OpenAI, they will assist the project rather than compete with it.

For several years, Altman has served as YC chairman. He sends countless texts and emails to founders every day and tracks how quickly people respond, as he wrote on his blog, believing that response time is "one of the most significant differences between great founders and mediocre founders." In 2017, he considered running for governor of California. He once "complained about politics and state government at a dinner party, and someone said, 'You should stop complaining and do something,'" he told me. "I thought, 'Okay.' He released a policy slate, "United Slate," outlining three core principles: tech prosperity, economic fairness, and personal freedom. A few weeks later, Altman dropped out of the race.

In early 2018, Musk attempted to take control of OpenAI, claiming the organization was falling behind Google. By February, Musk had left, leaving Altman in charge.

At the end of May, a few months later, Altman's father had a heart attack while rowing on Creve Coeur Lake outside St. Louis and passed away in the hospital. Annie told the reporter that at the funeral, Sam allocated five minutes for each of Altman's four children to speak. She ranked the family's emotional expressiveness during her time. She put Sam and her mother last.

04. The Moore's Law Behind GPT

In March 2021, Altman published an article titled "The Moore's Law of Everything." The article begins with, "My work at OpenAI reminds me every day that the scale of socio-economic change is happening faster than most people think… If public policy doesn't adjust accordingly, most people's circumstances will eventually be worse than they are now."

The Moore's Law, applicable to microchips, states that the number of transistors on a chip roughly doubles every two years, while the price drops by half. Altman's proposed "Moore's Law of Everything" assumes that "for decades, the price of everything, such as housing, education, food, clothing, has been halving every two years."

When Altman wrote this article, he had already left YC and was fully focused on OpenAI. In the spring of 2019, under his leadership, the company's first move was to establish a for-profit subsidiary. It turned out that building artificial intelligence was very expensive; Altman needed money. By the summer, he had raised $1 billion from Microsoft. Some employees resigned, feeling uneasy about moving away from the "greatest benefit of humanity" mission. However, surprisingly, few people were dissatisfied with this change.

A friend of Altman's inside said, "What, is Elon, worth hundreds of billions, going to be like 'naughty Sam'?" Altman refused to take the company public, and initially set a cap of 100 times the return for investors at OpenAI. But many people thought it was just a visual move. A billion times a hundred is a lot of money. Altman's friend said, "If Elizabeth Warren came and said, 'Oh, you've turned this into a for-profit company, you evil tech person,'" "everyone in the tech world would say, 'Go home.'"

Altman continues to participate in his racing (one of his favorite cars is the Lexus LFA, which was discontinued in 2013, according to HotCars, "costing at least $950,000"). In the early days of the pandemic, he wore a gas mask from the Israeli Defense Forces. He bought a ranch in Napa. (Altman is a vegetarian, but his partner, Melbourne-based computer programmer Oliver Mulherin, "likes cows," Altman said.) He bought a $27 million house on Russian Hill in San Francisco. He has more and more friends. In 2021, Diane von Furstenberg called him "one of my most recent, very, very close friends." Seeing Sam is like seeing Einstein.

Meanwhile, as OpenAI began selling the rights to use its GPT software to businesses, Altman was brewing a series of side projects in preparation for reshaping the world with artificial intelligence. He invested $375 million in the speculative fusion company Helion Energy. If Helion succeeds, Altman hopes to control one of the world's cheapest sources of energy. He invested $180 million in Retro Biosciences, aiming to extend human lifespan by ten years. Altman also conceived and raised $115 million for the "Worldcoin" project. The "Worldcoin" project involves scanning the irises of people around the world by gazing into a sphere called "Orb." Each iris fingerprint is then linked to a crypto wallet, and Worldcoin deposits currency into that wallet. This will address two problems created by artificial intelligence: distinguishing between humans and non-humans - which becomes necessary as AI further blurs the line between humans and non-humans; and distributing currency - another problem created by AI.

This is not a portfolio of someone as ambitious as Zuckerberg. Compared to Altman, Zuckerberg seems somewhat conservative, content with "building a city-state," as tech writer and podcaster Jathan Sadowski put it. This is a collection of works by someone as ambitious as Musk, someone who takes an "imperialistic approach." Sadowski said, "He really sees himself as the greatest person in the world, a Nietzschean Übermensch." He will create things that will destroy us and save us from them at the same time.

Subsequently, on November 30, 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT. The software attracted 100 million users within two months, making it the greatest product release in tech history. Two weeks earlier, Meta released Galactica, but the company took it down three days later because the robot couldn't distinguish truth from falsehood. ChatGPT also lied and created illusions. But Altman still released it and considered it a virtue. The world needs to get used to this. We need to make decisions together.

A former colleague who worked with Altman in the early years of OpenAI told a reporter, "Sometimes, being unethical is what sets a successful CEO or product apart from the rest. "Facebook isn't that interesting technologically, so why does Zuckerberg win?" He can "scale faster, build products, and not get bogged down."

05. The Oppenheimer Moment

In May 2023, Altman began a global tour of 22 countries and 25 cities. It was initially supposed to be a meet-and-greet with ChatGPT users, but it turned into a "socialite party." Altman would sometimes be in a suit and tie, sometimes in a gray sweater, showcasing himself as the inevitable new tech superpower to diplomats. He met with UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, French President Emmanuel Macron, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, and Israeli President Isaac Herzog. He posed for a photo with Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission. In the photo, she looked elegant and serene, while he looked like "Where's Waldo" - his phone in the front pocket clearly visible, his green eyes bright with fatigue and cortisol.

Later, Altman returned home and seemed to not only shed his attire but also his psychological baggage. From late June to mid-August, he tweeted a lot. If you want to understand him more authentically, Twitter is the best place.

Base models trained on large datasets can perform a wide range of tasks. Developers use base models as the foundation for powerful generative AI applications, such as ChatGPT.

Tonight's action: Barbie or Oppenheimer?

Altman conducted a poll. Barbie lost, 17% to 83%.

Alright, choosing Oppenheimer.

The next morning, Altman returned to express his disappointment.

I hope Oppenheimer's movie can inspire a generation of children to become physicists, but it really didn't meet the goal.

Let's make that movie!

(I think The Social Network successfully did this for startup founders).

Astute readers may be puzzled by Altman's work. For years, Altman has compared himself to a bomb maker. He once told a reporter that his and Oppenheimer's birthdays are the same. He relayed Oppenheimer's words to Cade Metz of The New York Times: "The emergence of technology is because it is possible." Therefore, Altman wouldn't be surprised if Christopher Nolan didn't create an inspiring work in his biopic. Oppenheimer spent the latter part of his life feeling ashamed and regretful for making atomic bombs. "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds" - this is the most famous line from the Bhagavad Gita, and it's also what Oppenheimer told NBC News about his thoughts during the Trinity nuclear test. (This line also appears twice in the movie).

Altman has always linked himself to Oppenheimer in his world tour speeches, discussing (in vague terms) the existential risks posed by artificial intelligence and (very specific terms) advocating for the establishment of a regulatory body modeled after the International Atomic Energy Agency. The International Atomic Energy Agency was approved by the United Nations in 1957, four years after its establishment. The agency's mission - dedicated to international peace and prosperity - sounds like a great analogy to the layperson. But it has troubled experts.

One criticism is about its political cynicism. Sadowski said, "You say, 'I'm going to regulate,' and then you say, 'This is a very complex and technical topic, so we need a complex and technical organization to do this,' but you know very well that this organization will never be established." Sadowski said, "Or, if it is established, hey, that's okay, because you built its DNA."

Another issue is ambiguity. Heidy Khlaaf, an engineer specializing in evaluating and validating safety protocols for drones and large nuclear power plants, explained to me that to reduce the risk of a technology, you need to precisely define what the technology can do, how it can help and harm society. (Perhaps someone will use AI to invent superbugs; perhaps someone will use AI to launch nuclear missiles; perhaps AI itself will backfire on humans - the solutions for each scenario are not clear). Furthermore, Khlaaf believes that we don't need a new organization. AI should be regulated within its scope of use, just like any other technology. AI built using copyrighted materials should be regulated by copyright law. AI used in aviation should also be subject to corresponding regulations. Finally, if Altman is serious about strict safety protocols, then he should take the smaller risks he perceives more seriously.

"If you can't even make your system not discriminate against Black people" - a phenomenon known as algorithmic bias, affecting everything from how job applicants are ranked to which faces are labeled as most attractive - "how can you stop it from destroying humanity?" Khlaaf asked. The hazards in engineering systems are complex. "A small software error can destroy New York's power grid. Trained engineers know this." Every company in these fields, every top competitor in the field of AI, has enough resources and basic engineering knowledge to figure out how to reduce the hazards in these systems. Choosing not to do so is a choice."

On the same day Altman released the Oppenheimer vs. Barbie poll, he also published an article:

All "creativity" is a recombination of things that have happened in the past, multiplied by ε and the quality of the feedback loop, and the number of iterations.

People think they should maximize ε, but the trick is to maximize the other two.

Throughout the summer and fall, OpenAI faced increasing pressure as it was accused of training its models and making money on datasets filled with copyrighted works. Michael Chabon organized a class-action lawsuit after learning that his book was used without permission for ChatGPT teaching. The Federal Trade Commission launched an investigation into the company's alleged widespread violations of consumer protection laws. Now, Altman believes that creativity doesn't actually exist. No matter how prominent writers or angry illustrators view their individuality or value, they are just remixing old ideas. Just like OpenAI's products.

In terms of wording, mathematical terms give it a reliable appearance. "Mathiness" is a term coined by Nobel laureate Paul Romer in 2015 to describe mathematical language not used to clarify but to mislead. "The charm of mathematical language is that it can convey the truth of the world in simple terms - E = MC2," said Noah Giansiracusa, a mathematics and data science professor at Bentley University. "I repeatedly read his tweets and still don't know how to parse them, or what he's trying to convey."

Giansiracusa translated Altman's words into symbols. "Using C to represent creative things, R for the remixing of past things, Q for the quality of the feedback loop, and N for the number of iterations, is he saying C = R + epsilon*Q*N or C = (R + epsilon)*Q*N?" Giansiracusa said Altman's wording doesn't clearly indicate the order of operations. "'and N' - and the number of iterations - does it imply something other than multiplication? Or…"

May 22, 2023: Posing with Spanish President Sánchez. Photo: Pool Moncloa/Jorge Villar

06. The Future of OpenAI

On June 22, 2023, Altman dressed in a tuxedo and attended a White House dinner with his partner Oliver Mulhern.

He looked like a character from a time-travel movie of the 90s, too small and too young to wield the power he should have. But most of the time, he was just acting. His evening suit looked neat, in stark contrast to the messy aesthetic of Sam Bankman-Fried, another famous figure from "Silicon Valley," whose untidy appearance now seemed like evidence of moral decay. Since Altman took over as CEO of OpenAI, the company has not only downplayed its non-profit identity but has also become less open and less of a company. It is no longer very open, no longer publicly sharing its training data and source code, and no longer allowing others the possibility to analyze and improve its technology. It has abandoned the work of "serving the greater good of humanity." But what else can be done? During a global tour in Munich, Altman asked a full audience if they wanted OpenAI to open-source its next generation LLM GPT-5 after its release.

The audience's answer was affirmative.

Altman said, "Wow, we definitely won't do that, but it's interesting to know."

In August, in his office, Altman continued to express his views at length. I asked him what he had been doing in the past 24 hours. He said, "One thing I was researching yesterday is: we are trying to figure out if we can make artificial intelligence align with human values. We have made good progress technically. Now there's a harder problem: whose values?"

He also had lunch with the mayor of San Francisco, trying to reduce his 98-page to-do list, and lifted weights (although he somewhat resignedly said, "I've given up on trying to make myself truly muscular"). He welcomed new employees. He had dinner with his brother and Oliver. He went to bed at 8:45 PM.

Imperialism is cloaked in a beautiful exterior, leading people astray. He told a reporter that one of Altman's most cherished possessions is a mezuzah (a Jewish doorpost scroll) that his grandfather kept in his pocket all his life. He and Oliver are trying to have children as soon as possible, and he loves a large family. He laughs happily, sometimes having to lie on the floor to catch his breath. He is "trying to find ways to integrate people's desires into our construction." He knows that "artificial intelligence is not a purely beneficial story," "something will be lost here," "the aversion to loss is super endearing and natural. People don't want to hear stories of themselves being sacrificed."

He said that his public image "is only tangentially related to me."

Reference: https://nymag.com/intelligencer/article/sam-altman-artificial-intelligence-openai-profile.html

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。