Understanding MEV and recognizing its risks is essential for navigating the digital world, which is full of opportunities but also fraught with dangers.

Written by: Daii

Last Wednesday (March 12), a crypto trader lost $215,000 in a single MEV attack, which went viral.

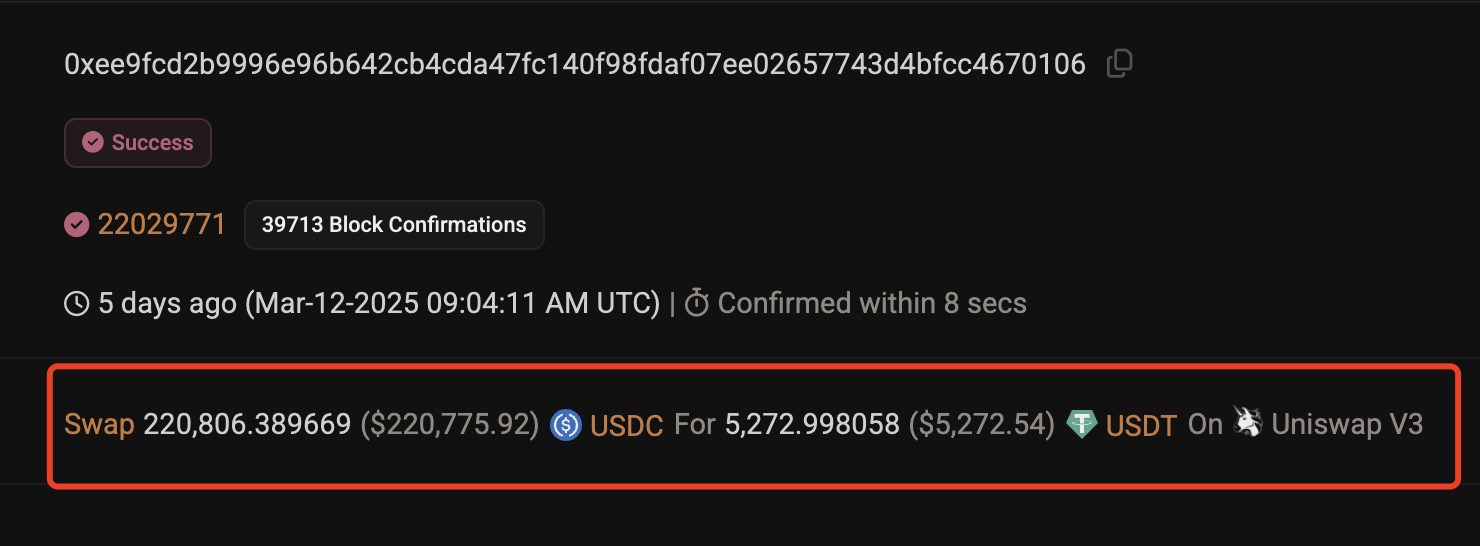

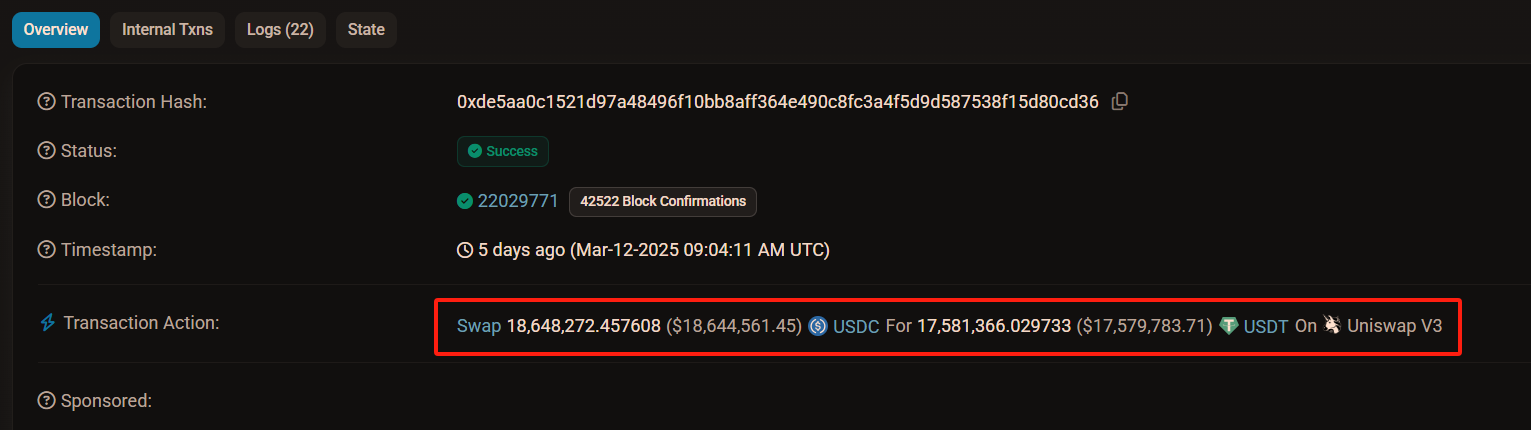

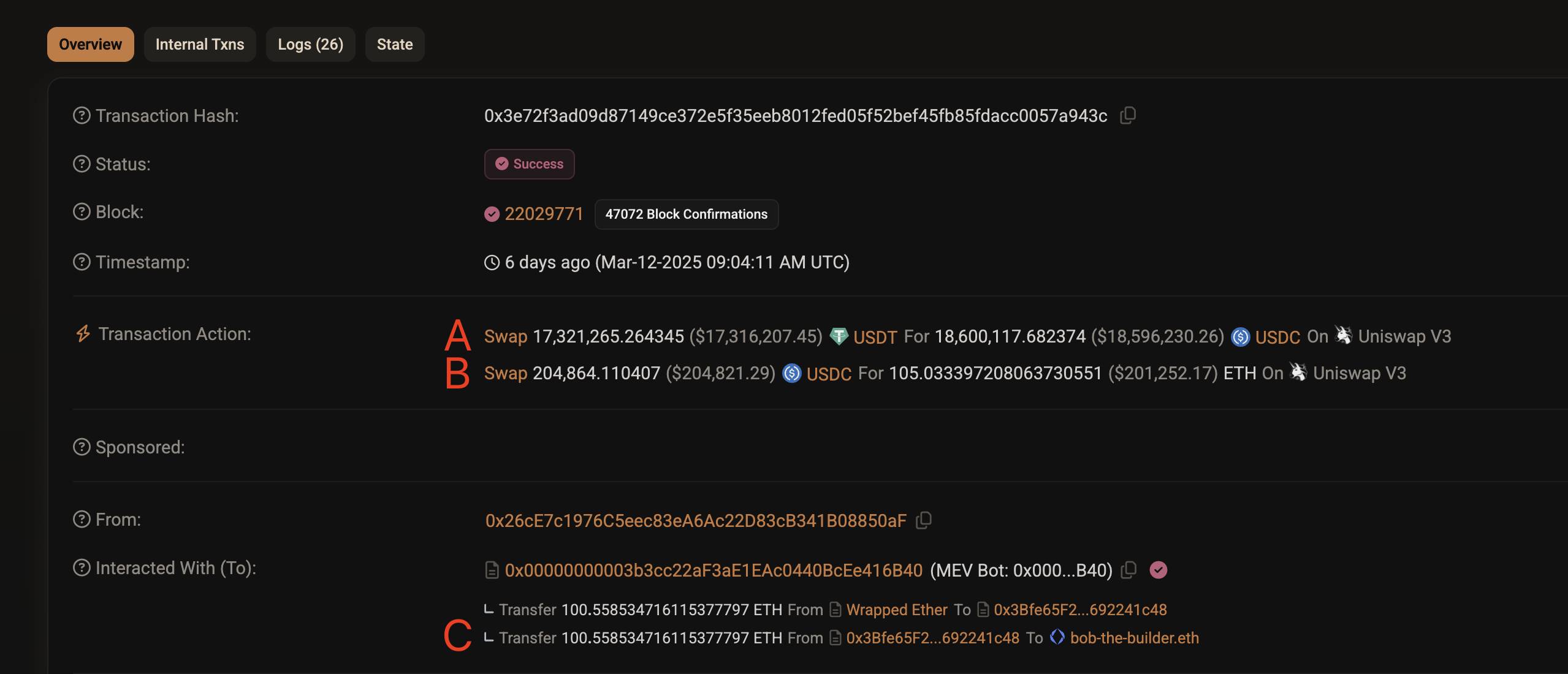

In simple terms, this user intended to exchange $220,800 worth of USDC stablecoins for an equivalent amount of USDT in the Uniswap v3 trading pool, but ended up receiving only 5,272 USDT, resulting in a rapid loss of $215,700 in just a few seconds, as shown in the image below.

The image above is a screenshot of the on-chain record of this transaction. The fundamental reason for this tragedy is that the user fell victim to the blockchain world's notorious "Sandwich Attack."

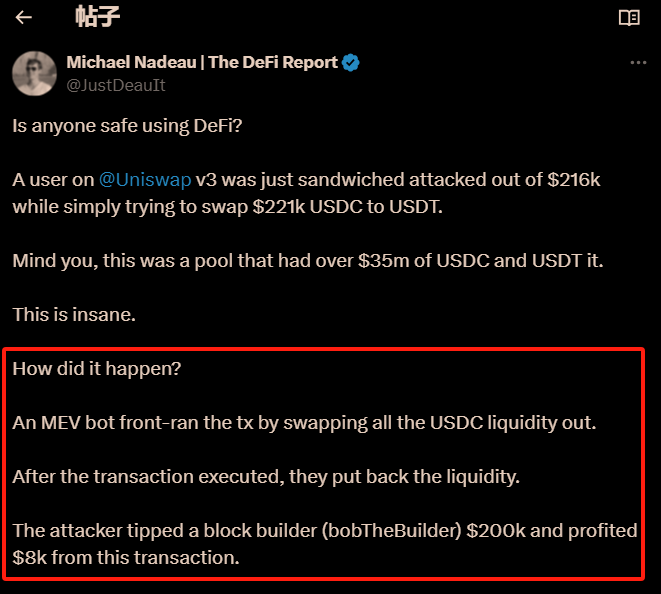

The first to disclose this MEV attack was Michael (see the image above), who explained:

An MEV bot front-ran the tx by swapping all the USDC liquidity out. After the transaction executed, they put back the liquidity. The attacker tipped a block builder (bobTheBuilder) $200k and profited $8k from this transaction.

However, there was a typo in the above content; the MEV attack bot swapped out a large amount of USDT, not USDC.

After reading his explanation and the news reports, you might still be confused due to the many new terms, such as Sandwich Attack, front-ran the tx, put back the liquidity, and tipped a block builder.

Today, we will take this MEV attack as an example to break down the entire process and give you a glimpse into the dark world of MEV.

First, we need to explain what MEV is.

1. What is MEV?

MEV, originally known as Miner Extractable Value, refers to the additional profit that miners can obtain by reordering, inserting, or excluding transactions within a blockchain block. This manipulation can lead to ordinary users incurring higher costs or receiving less favorable transaction prices.

As blockchain networks like Ethereum transitioned from a Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus mechanism to a Proof-of-Stake (PoS) consensus mechanism, the power to control transaction ordering shifted from miners to validators. Consequently, the term evolved from "Miner Extractable Value" to "Maximal Extractable Value."

Despite the name change, the core concept of extracting value by manipulating transaction order remains the same.

The key takeaway is that MEV exists because previous miners and current validators have the right to order transactions in the mempool. This ordering occurs within a block, and Ethereum currently produces a block approximately every 11 seconds, meaning this power is exercised every 11 seconds. Similarly, this MEV attack was also achieved through validator ordering.

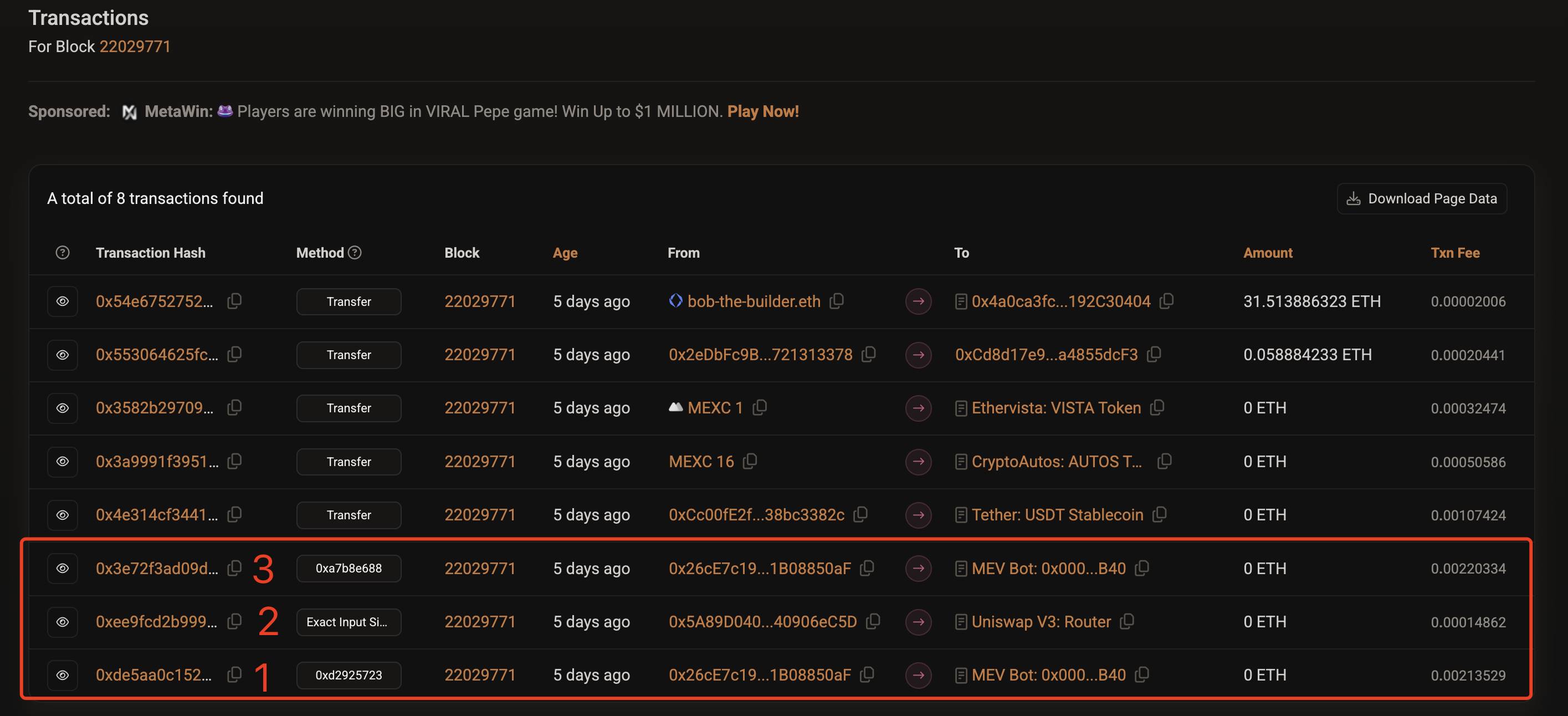

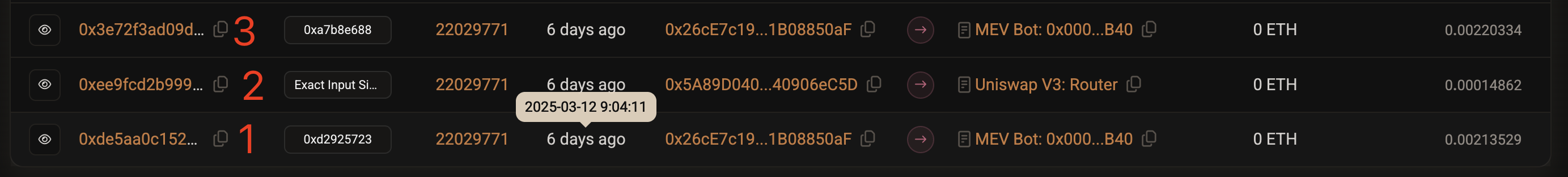

Clicking this link will show you the transaction details contained in block number 22029771 related to this attack, as shown in the image below.

Note that transactions 1, 2, and 3 in the image above are the MEV attack mentioned at the beginning of this article, and this order was arranged by the validator (bobTheBuilder). Why can this happen?

2. The Principle of MEV

To understand how MEV works, we first need to grasp how blockchain records and updates information.

2.1 Blockchain State Update Mechanism

A blockchain can be viewed as a continuously growing ledger that records all transactions that occur. The state of this ledger, such as the balance of each account and the reserves of various tokens in the Uniswap trading pool, is determined by previous transactions.

When a new block is added to the blockchain, all transactions contained in that block are executed in the order they are arranged within the block. With each transaction executed, the global state of the blockchain changes accordingly.

This means that not only is the order of blocks important, but the order of transactions within a block is also crucial. So how is the transaction order within a block determined?

2.2 Validators Determine Transaction Order

When a user initiates a transaction on the blockchain network, such as converting USDC to USDT through Uniswap, the transaction is first broadcast to the nodes in the network. After preliminary validation, the transaction enters an area known as the "mempool." The mempool acts as a waiting area where transactions have not yet been confirmed and added to the next block of the blockchain.

Previous miners (in PoW systems) and current validators (in PoS systems) have the authority to select transactions from the mempool and decide the order of these transactions in the next block.

The order of transactions in a block is critical. Before a block is finalized and added to the blockchain, the transactions within that block are executed in the order determined by the validator (e.g., bobTheBuilder). This means that if a block contains multiple transactions interacting with the same trading pool, the execution order of these transactions will directly affect the outcome of each transaction.

This ability allows validators to prioritize certain transactions, delay or exclude others, and even insert their own transactions to maximize profits.

The ordering of this transaction is equally important; any slight deviation could prevent a successful attack.

2.3 Transaction Ordering in This MEV Attack

Let's briefly understand the three transactions related to this MEV attack:

Transaction 1 (the attacker's first transaction): Executed before the victim's transaction. The purpose of this transaction is typically to drive up the price of the token the victim intends to trade.

Transaction 2 (the victim's transaction): Executed after the attacker's first transaction. Due to the attacker's prior actions, the price in the trading pool is now unfavorable for the victim, who must pay more USDC to exchange for an equivalent amount of USDT or can only receive less USDT.

Transaction 3 (the attacker's second transaction): Executed after the victim's transaction. The purpose of this transaction is typically to profit from the new price changes caused by the victim's transaction.

The validator for this MEV attack is bob-The-Builder.eth, who is responsible for arranging the transactions in the order of 1, 2, 3. Of course, bobTheBuilder did not do this for free; he earned over 100 ETH from this arrangement, while the initiator of the MEV attack only made $8,000. Their income comes directly from the victim's second transaction.

In summary, the attacker (MEV bot) and the validator (bobTheBuilder) colluded, causing the victim of the second transaction to lose $215,000, with the attacker receiving $8,000 and the validator $200,000 (over 100 ETH).

The method they used for the attack has a vivid name—Sandwich Attack. Next, we will explain each transaction one by one to help you fully understand how the relatively complex Sandwich Attack of MEV works.

3. Full Analysis of the Sandwich Attack

It is called a Sandwich Attack because the attacker's two transactions (Transaction 1 and Transaction 3) are placed before and after the victim's transaction (Transaction 2), making the entire transaction order resemble a sandwich structure (see the image above).

Transactions 1 and 3 serve different functions. In simple terms, Transaction 1 is responsible for the crime, while Transaction 3 is responsible for collecting the spoils. Specifically, the entire process is as follows:

3.1 Transaction 1, responsible for raising the price of USDT

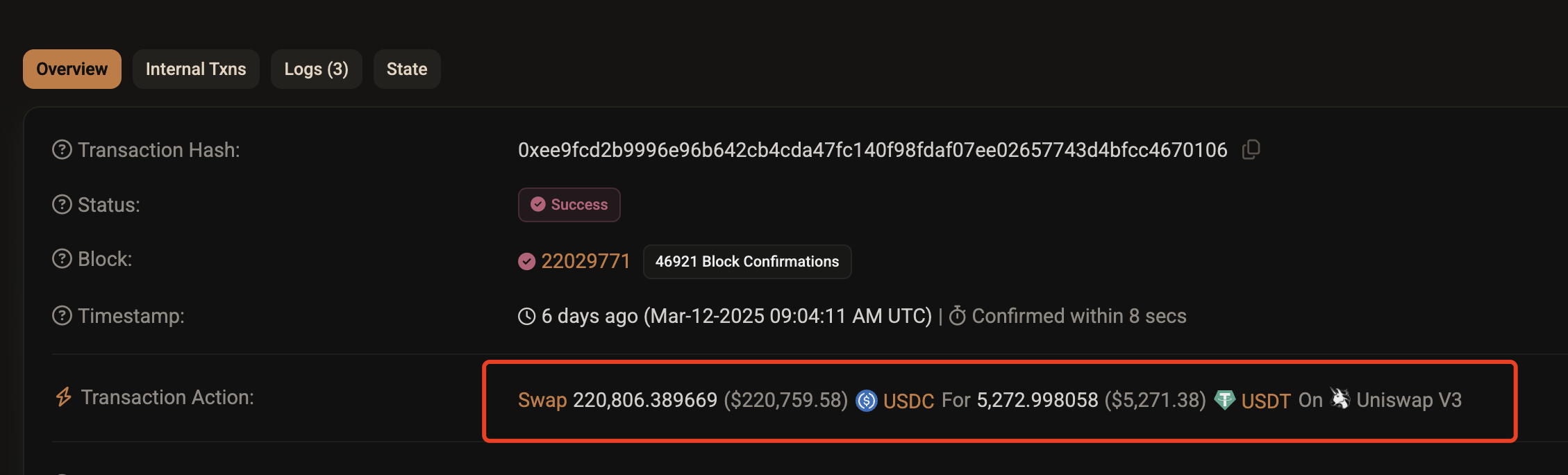

Clicking the link for Transaction 1 in the image above, you will see the details of Transaction 1. The attacker raised the price of USDT directly by swapping all 17.58 million USDT with 18.65 million USDC, as shown in the image below.

At this point, the liquidity pool contains a large amount of USDC and a small amount of USDT. According to news reports, before the attack, Uniswap's liquidity had approximately 19.8 million USDC and USDT each. After executing Transaction 1, only 2.22 million USDT remained in the pool (19.8 - 17.58), while the USDC balance increased to about 38.45 million (19.8 + 18.65).

At this point, the exchange rate between USDC and USDT in the pool is no longer 1:1, but rather 1:17, meaning that 17 USDC is needed to exchange for 1 USDT. However, this ratio is only approximate because this pool is V3, and the liquidity is not evenly distributed.

There's one more thing I need to tell you. In fact, the attacker did not use the entire 1,865,000 USDC at once; the actual amount of USDC used was 1,090,000, which is less than 6%. How did they achieve this? We will explain in detail after we finish discussing the attack.

3.2 Transaction 2: Executing 220,000 USDC to Exchange for USDT

Clicking the link for Transaction 2 in the image above reveals the following.

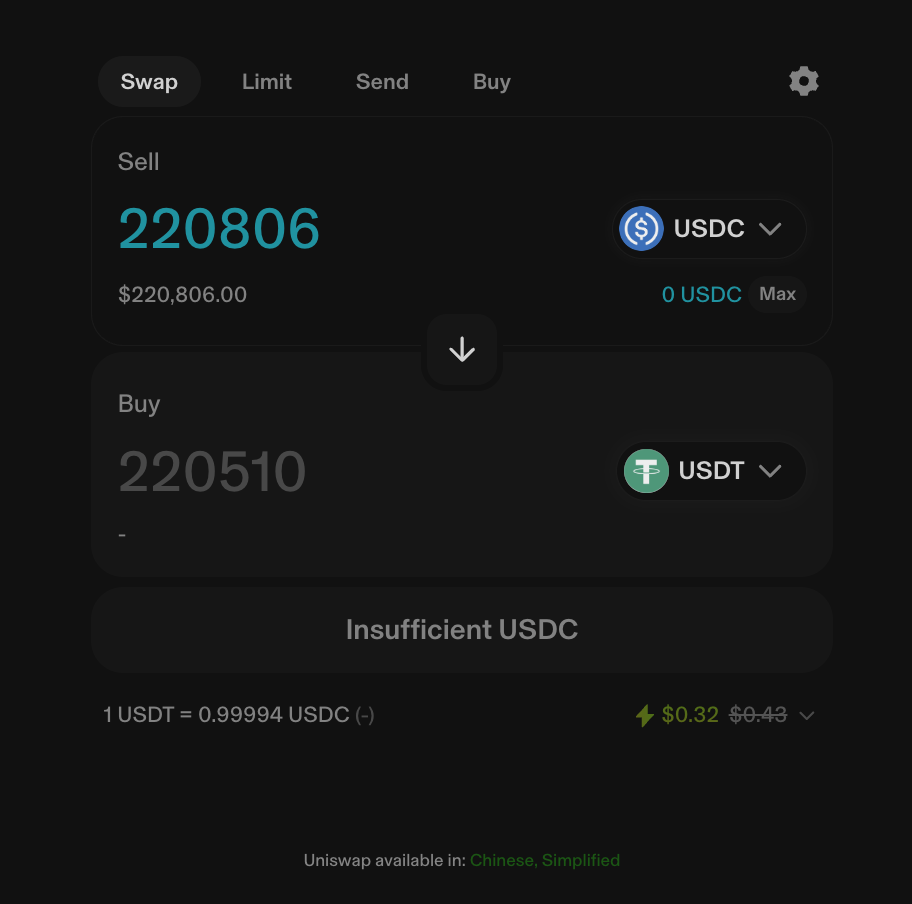

As shown in the image, due to the impact of Transaction 1, the victim's Transaction 2 only received 5,272 USDT for 220,000 USDC, resulting in an unnoticed loss of 170,000 USDT. Why do I say it was unnoticed? Because if the victim was trading through Uniswap, they would have seen the following interface when submitting the transaction.

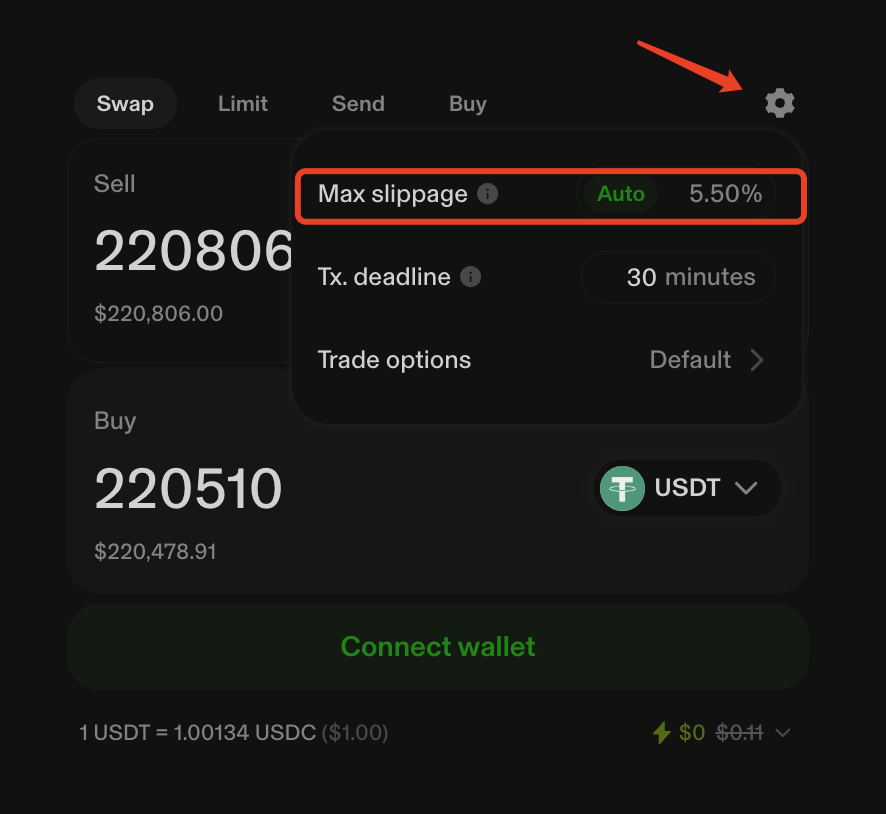

From the image, you can see that the victim was guaranteed to receive at least 220,000 USDT. The reason the victim ultimately received only a little over 5,000 USDT is due to significant slippage, exceeding 90%. However, Uniswap has a default maximum slippage limit of 5.5%, as shown in the image below.

This means that if the victim was trading through the Uniswap frontend, they should have received at least 208,381 USDT (220,510 * 94.5%). You might wonder why the blockchain record shows that this transaction was conducted on "Uniswap V3."

This is because the frontend and backend of blockchain transactions are separate. The "Uniswap V3" mentioned refers to the USDC-USDT liquidity pool of Uniswap, which is public, and any trading frontend can use this pool for trading.

Because of this, some people suspect that the victim is not just an ordinary person; otherwise, such significant slippage wouldn't occur, and they might be using the MEV attack for money laundering. We will discuss this later.

3.3 Transaction 3: Harvesting + Dividing the Spoils

Clicking the link allows you to view the details of Transaction 3, as shown in the image above. Let's discuss Transactions A, B, and C.

Transaction A: Restores the pool's liquidity to normal by exchanging 17.32 million USDT for 18.60 million USDC;

Transaction B: Prepares to divide the spoils by exchanging part of the profit—204,000 USDC for 105 ETH;

Transaction C: Divides the spoils by paying 100.558 ETH to the validator bob-The-Builder.eth.

Thus, the sandwich attack concludes.

Now, let's answer an important question mentioned earlier: How did the attacker achieve an attack worth 18 million USDC with only 1,090,000 USDC?

4. How the Attacker Achieved an 18 Million USDC Pool Attack

The reason the attacker could execute an 18 million dollar attack with only 1,090,000 USDC in capital is due to a magical and special mechanism in the blockchain world—Uniswap V3's Flash Swap.

4.1 What is Flash Swap?

In simple terms:

Flash Swap allows users to first withdraw assets from the Uniswap pool in a single transaction and then repay with another asset (or the same asset plus fees).

As long as the entire operation is completed within the same transaction, Uniswap allows this "take first, pay later" behavior. Note that it must be completed within the same transaction. This design is intended to ensure the security of the Uniswap platform:

Zero-risk borrowing: Uniswap allows users to temporarily withdraw funds from the pool without collateral (similar to borrowing), but they must repay immediately at the end of the transaction.

Atomicity: The entire operation must be atomic; it either succeeds completely (funds are returned) or fails entirely (the transaction is rolled back).

The original intention of Flash Swap was to facilitate on-chain arbitrage more effectively, but unfortunately, it has been exploited by MEV attackers, becoming a tool for market manipulation.

4.2 How Flash Swap Assisted the Attack

Now, let's look at the images step by step to understand how the Flash Swap was implemented in this attack, as shown in the image below.

F1: The attacker borrowed 1,090,000 USDC from AAVE using their own 701 WETH;

F2: The attacker initiated a Flash Swap request, first withdrawing 17.58 million USDT from the Uniswap pool (no payment required at this point), temporarily increasing the attacker's account by 17.58 million USDT;

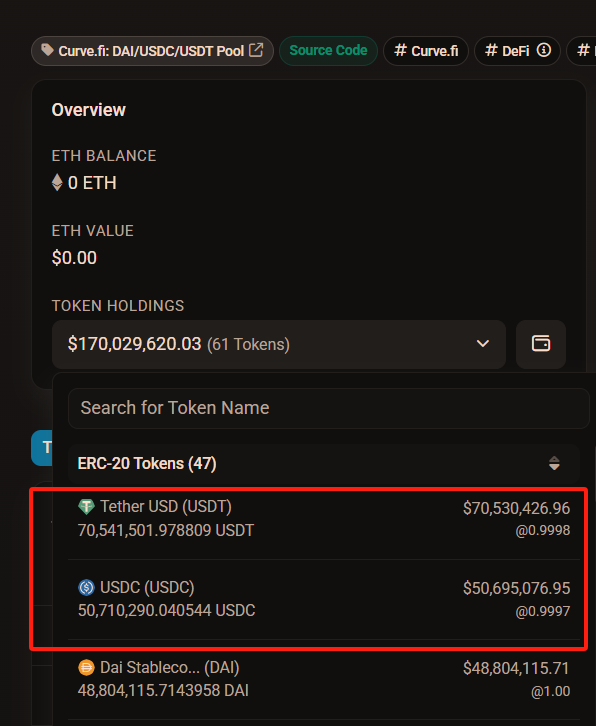

F3: The attacker quickly deposited this 17.58 million USDT into the Curve pool, exchanging it back for 17.55 million USDC. The attacker's USDT decreased by 17.58 million, while USDC increased by 17.55 million. From the image below, you can see that the attacker chose Curve because it has ample liquidity, with over 70.54 million USDT and 50.71 million USDC, resulting in relatively low slippage.

- F4: The attacker then repaid Uniswap with the 17.55 million USDC obtained from Curve, plus their original 1,090,000 USDC (borrowed from AAVE), totaling 18.64 million USDC, completing the Flash Swap;

After this transaction (Transaction 1), the attacker's account balance decreased by 1,090,000 USDC because only 17.55 million USDC of the 18.64 million USDC returned to Uniswap was obtained from Curve, while the remaining 1,090,000 USDC was the attacker's own funds.

You should notice that this transaction actually resulted in a loss of 1,090,000 for the attacker. However, in the subsequent Transaction 3, also using the Flash Swap method, not only did they recover the 1,090,000 USDC, but they also made a profit of over 200,000.

Now, let's analyze Transaction 3 step by step based on its data.

K1: The attacker used Flash Swap to withdraw 18.60 million USDC from Uniswap;

K2: The attacker exchanged part of the 18.60 million USDC just withdrawn from Uniswap for 17.32 million USDT;

K3: The attacker returned the 17.32 million USDT obtained from Curve to Uniswap, completing the Flash Swap. You need to note that the attacker only spent 17.30 million USDC to obtain 17.32 million USDT through K2. Of the remaining 1.30 million (18.60 - 17.30) USDC, 1.09 million was their own funds, while the remaining 210,000 USDC was the profit from this attack.

K4: The attacker repaid the principal to AAVE, took back their 701 WETH, exchanged 200,000 USDC for 105 ETH, and paid 100.558 ETH to the validator as a tip (about 200,000 dollars), leaving themselves with less than 10,000 dollars in profit.

You might be surprised why the attacker was willing to give away up to 200,000 dollars in profit to the validator.

4.3 Why Give a 200,000 Dollar "Tip"?

In fact, this is not generosity but a necessary condition for the success of the sandwich attack, which is an MEV attack:

The core of a successful attack is the precise control of transaction order, and the one controlling the transaction order is the validator (bobTheBuilder).

The validator not only helps the attacker ensure that the victim's transaction is positioned between the attack transactions but, more importantly, ensures that other competing MEV bots cannot cut in line or interfere with the smooth completion of the attack.

Therefore, the attacker is willing to sacrifice the vast majority of their profit to ensure the success of the attack while retaining a certain profit for themselves.

It should be noted that MEV attacks also have costs; there are costs associated with Uniswap's Flash Swap and Curve trading. However, since the fees are relatively low, around 0.01% to 0.05%, they are negligible compared to the profits from the attack.

Finally, I want to remind you that defending against MEV attacks is actually quite simple: just set a slippage tolerance of no more than 1% and execute large trades in smaller batches. So, you need not be deterred from trading on DEXs (decentralized exchanges) due to fear of such attacks.

Conclusion: Warnings and Insights from the Dark Forest

The $215,000 MEV attack incident is undoubtedly another brutal manifestation of the "dark forest" principle in the blockchain world. It vividly reveals the complex game of exploiting mechanism loopholes for profit in a decentralized, permissionless environment.

From a higher perspective, the emergence of MEV reflects the double-edged sword effect of blockchain transparency and programmability.

On one hand, all transaction records are publicly accessible, allowing for tracking and analysis of attack behaviors;

On the other hand, the complex logic of smart contracts and the determinism of transaction execution provide savvy participants with opportunities to exploit.

This is not merely a simple hacking act but a profound understanding and utilization of the underlying mechanisms of blockchain, testing the robustness of protocol design and challenging participants' risk awareness.

Understanding MEV and recognizing its risks is essential for better navigating this digital world, which is full of opportunities but also harbors hidden dangers. Remember, in the "dark forest" of blockchain, only by respecting the rules and enhancing awareness can one avoid becoming the next prey to be devoured.

This is also the effect I aim to achieve through this article.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。