Money rules everything.

Author: Joel John

Translation: Deep Tide TechFlow

When people start to revisit the discussion around "fundamentals," you know the market conditions are not optimistic. Today's article aims to explore a simple yet important question: Should tokens generate revenue? If so, should teams buy back their own tokens? As with most complex issues, there are no clear answers here—the path forward is paved more by honest dialogue.

If you are a founder or a member of a DAO considering a token buyback plan, we would be very willing to discuss this with you. You can reply directly to this email or DM me on Twitter.

Alright, now let's get to the point…

Life is just a game of capitalism.

This article is inspired by a series of conversations I had with Covalent's Ganesh. The discussions covered the seasonality of revenue, the evolution of business models, and whether token buybacks are the best use of protocol capital. This article also serves as a supplement to my Tuesday piece on the “stagnation” in the crypto industry.

Hello everyone!

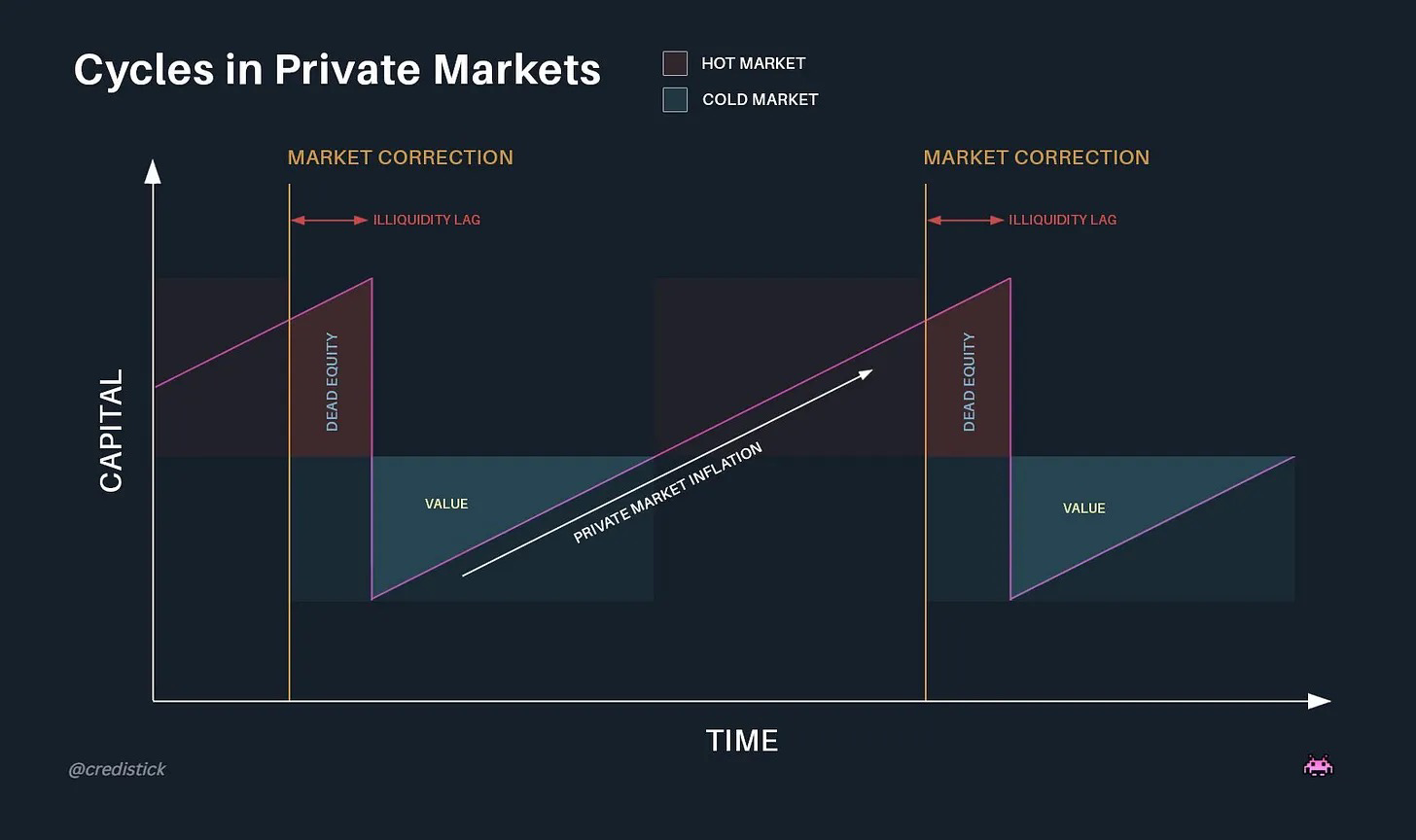

The private capital market (such as venture capital) always swings between liquidity excess and scarcity. When these assets become liquid and external capital floods in, euphoric sentiment drives prices up. Think of newly listed IPOs or token launches. This newly acquired liquidity allows investors to take on more risk, thereby fostering the birth of a new generation of companies. When asset prices rise, investors shift their funds to earlier-stage applications, hoping for higher returns than benchmark assets like Ethereum (ETH) or Solana (SOL).

This phenomenon is a "feature" of the market, not a "bug."

The liquidity in the crypto market typically follows the Bitcoin halving cycle. Historical data shows that within six months after a Bitcoin halving, the market usually experiences a surge. In 2024, the inflow of ETF funds into Bitcoin and Michael Saylor's massive purchases (he spent $22.1 billion on Bitcoin last year) have become a "reservoir" for Bitcoin's supply. However, the rise in Bitcoin's price has not spurred an overall rebound in smaller altcoins.

We are currently in a period of liquidity tightening for capital allocators, with attention dispersed across thousands of assets, while founders who have dedicated years to token development find it difficult to ascribe real meaning to these tokens. When issuing "meme assets" is more financially rewarding than building real applications, who would bother to develop genuine applications? In previous cycles, Layer 2 (L2) tokens enjoyed a premium due to their perceived potential value, primarily driven by exchange listings and venture capital support. However, as more market participants enter, this perception (and valuation premium) is gradually fading.

The result is a decline in the value of L2 tokens, which limits their ability to support small products through subsidies, token revenue, and other means. The shrinkage in valuations forces founders to rethink an age-old question: Where does revenue actually come from?

Such Transactions

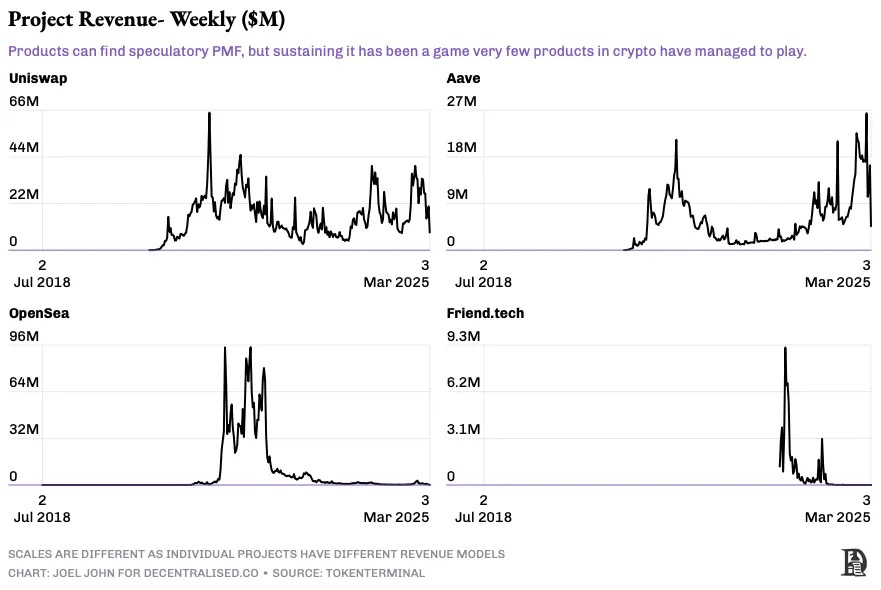

The chart above explains well how revenue typically operates in cryptocurrency. From a revenue structure perspective, the ideal state for most crypto products resembles that of Aave and Uniswap. These products have maintained stable fee income over the years due to their early market entry and the "Lindy effect." Uniswap can even further monetize by increasing front-end fees, indicating that consumer preferences have been deeply defined. One could say that Uniswap's impact on decentralized exchanges is akin to that of Google on search engines.

In contrast, the revenue of FriendTech and OpenSea exhibits clear seasonality. For instance, the NFT craze lasted for two quarters, while the speculation boom in social finance (Social-Fi) lasted only two months. For some products, speculative revenue is reasonable, provided the revenue scale is large enough and aligns with the product's intent. Many meme culture trading platforms have already entered the "over $100 million club" in fee revenue, a scale that most founders can only hope to achieve through tokens or acquisitions in the best-case scenario. But for most founders, such success is exceedingly rare.

Their focus is not on consumer applications but on infrastructure, and the revenue dynamics of infrastructure are entirely different.

Between 2018 and 2021, venture capital firms heavily funded developer tools, hoping developers could attract large user bases. However, by 2024, two major changes have occurred in the ecosystem:

The infinite scalability of smart contracts: Smart contracts achieve infinite scalability with limited human intervention. For example, Uniswap or OpenSea does not need to proportionally scale their teams as transaction volumes grow.

Advancements in artificial intelligence: The progress of LLMs (large language models) and AI has reduced the investment demand for crypto developer tools. Thus, this category is at a critical transformation point.

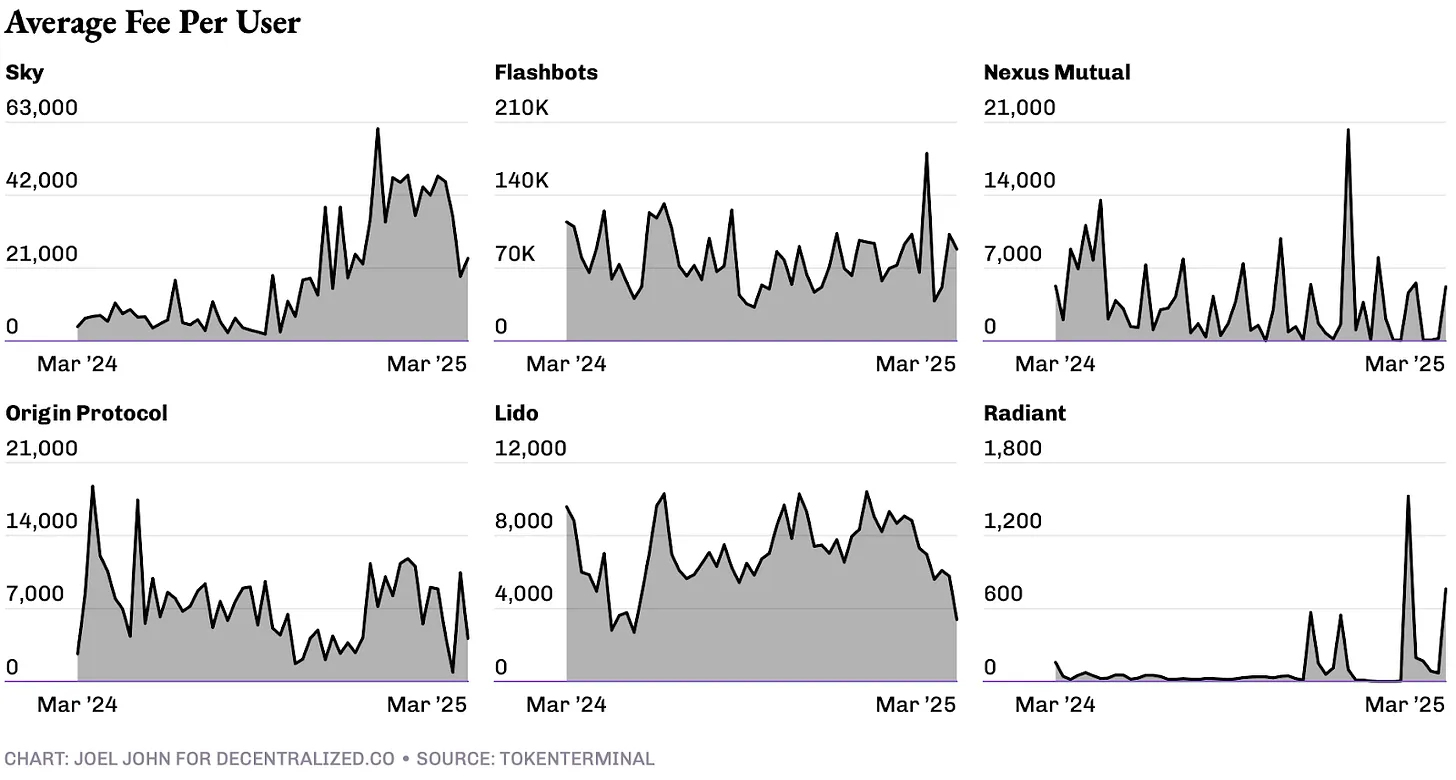

In Web2, the success of API-based subscription models was due to the vast number of online users. In Web3, it is a niche market, with only a few applications able to scale to millions of users. However, the advantage of Web3 lies in its higher "revenue per user" metric. Crypto users tend to spend more frequently on high-value transactions because the blockchain is essentially a "transmission track" for money. Therefore, in the next 18 months, most businesses will have to readjust their business models to directly generate revenue from users through transaction fees.

This model is not new. For example, Stripe initially charged per API call, while Shopify adopted a fixed subscription fee model, but both eventually shifted to charging a percentage of revenue. For Web3 infrastructure providers, this shift may manifest as lowering the barriers to API usage or even offering services for free until a certain transaction volume is reached, after which revenue sharing can be negotiated. This is an ideal hypothetical scenario.

So, what would this model look like in practice? We can take Polymarket as an example. Currently, the UMA protocol's tokens are used for dispute resolution, with tokens tied to dispute cases. The more markets there are, the higher the probability of disputes, which directly drives demand for UMA tokens. In a transaction-based model, the required margin could be a small percentage of the total betting amount, such as 0.10%. If the total betting amount for a presidential election is $1 billion, this would generate $1 million in revenue for UMA. In a hypothetical scenario, UMA could use this revenue to buy back and burn its tokens. This model has its advantages but also faces certain challenges, which we will explore further later.

Another example of a similar model is MetaMask. To date, the embedded swap feature of the MetaMask wallet has processed over $36 billion in transaction volume, generating over $300 million in revenue from this alone. The same logic applies to staking service providers like Luganode, whose revenue is based on the scale of user-staked assets.

However, in a market where the cost of API calls is decreasing, why would developers choose one infrastructure provider over another? Why would they opt for a certain oracle service that requires revenue sharing? The answer lies in network effects. A data provider that can support multiple blockchains, offer unparalleled data granularity, and index new chains faster will become the preferred choice for new products. The same logic applies to transaction-based service categories, such as intents or gasless swap solutions. The more blockchains supported, the lower the costs and faster the speeds, making it more likely to attract new products. This increase in marginal efficiency not only attracts users but also helps platforms retain them.

Burn Everything

The trend of linking token value to protocol revenue is not new. In recent weeks, several teams have announced mechanisms for buying back or burning their own tokens based on generated revenue. Notable mentions include Sky, Ronin, Jito, Kaito, and Gearbox.

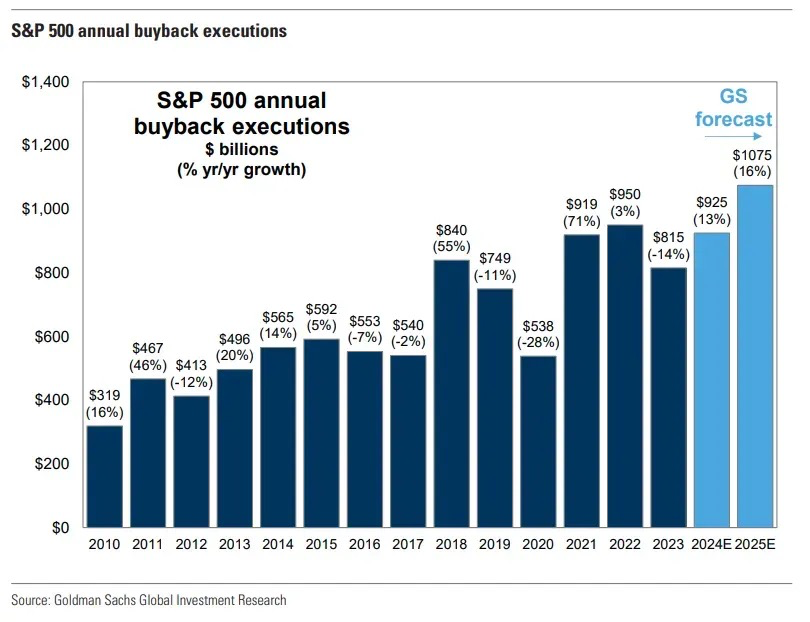

Token buybacks are similar to stock buybacks in the U.S. stock market—essentially a way to return value to shareholders (in this case, token holders) without violating securities laws.

In 2024, the amount of stock buybacks in the U.S. market alone reached $790 billion, compared to just $170 billion in 2000. Before 1982, stock buybacks were considered illegal. Apple has spent over $800 billion buying back its own stock in the past decade. Whether these trends will continue remains to be seen, but we can clearly observe a polarization in the market: one class of tokens has cash flow and is willing to invest in their own value, while another class has neither.

For most early-stage protocols or dApps, using revenue to buy back their own tokens may not be the optimal use of capital. One viable operational approach is to allocate sufficient funds to offset the dilution effect caused by new token issuance. This is precisely what the founder of Kaito recently explained regarding their token buyback method. Kaito is a centralized company that incentivizes users with tokens, obtaining centralized cash flow from enterprise clients and using a portion of it to execute buybacks through market makers. The number of tokens bought back is twice the number of newly issued tokens, effectively putting the network into a deflationary state.

Another approach can be seen in the practices of Ronin. This blockchain dynamically adjusts fees based on the number of transactions within each block. During peak usage periods, a portion of the network fees flows into Ronin's treasury. This is a way to control asset supply without directly buying back tokens. In both cases, the founders have designed mechanisms that link value to network economic activity.

In future articles, we will delve deeper into the impact of these operations on token prices and on-chain behavior. However, it is evident that as valuations decline and the influx of venture capital into the crypto space decreases, more teams will have to compete for the marginal funds flowing into the ecosystem.

Since blockchains are essentially financial infrastructure, most teams may turn to revenue models based on a percentage of transaction volume. When this happens, if teams have already tokenized, they will be motivated to implement a "buyback and burn" model. Those teams that can successfully execute this strategy will stand out in a liquid market. Alternatively, they may ultimately buy back their tokens at extremely high valuations. The actual outcome of such a scenario will only become clear in hindsight.

Of course, one day, all discussions about price, yield, and revenue may become irrelevant. Perhaps in the future, we will return to the era of throwing money at dog pictures or monkey NFTs. But for now, many founders concerned about survival have begun to engage in deep discussions around revenue and token burn.

Creating shareholder value,

Disclaimer:

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice.

Individuals associated with Decentralised.co may hold investments in CXT.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。