Author: Crypto V

Imagine you and your companions are standing within the blast radius of a nuclear bomb. In an instant, some are turned to ash, some have their limbs blown off, some are burned into charred shapes, some suffer severe burns, and some are left blind with scorched skin.

Sounds terrifying?

Now try replacing the nuclear bomb with the launch and spread of a new coin:

Some people are buying in on the exchange, instantly multiplying their investment by ten thousand; some are getting 10x; some are doubling their money; some are left hanging on a mountaintop, becoming the next victim in the story.

How many have you seen cursing $Libra and $TRUMP while urging Kanye to launch a coin? Why do they insist on chasing after it, knowing they might get burned?

It's not that they are foolish or simply love losing money; it's the nature of information dissemination. This set of rules applies not only to Crypto but also to all information arbitrage games in the real world. Let’s dive in.

Positive Suspicion Chain - How to Create a FOMO

I’m not sure how many of my readers have elementary school or doctoral degrees, but I’ll assume everyone has read "The Three-Body Problem." In the worldview of "The Three-Body Problem," there is an important fundamental theorem—suspicion chain:

“I do not know whether you have good intentions; I do not know whether you think you have good intentions; and I cannot assume whether you think I have good intentions.”

In this "dark forest" scenario, civilizations cannot communicate to confirm each other's intentions, nor can they choose to remain silent and allow the other to grow stronger. Therefore, the only optimal solution is to strike first and destroy the other.

This is an ultimate PVP prisoner’s dilemma, where all actions inevitably lead to the outcome of "ensuring destruction."

The scenario constructed by Liu Cixin is a confrontation between cosmic civilizations, while in the Crypto trading market, we can reverse-engineer a similar "dark forest zero-sum deadlock": FOMO (Fear of Missing Out).

The "Positive Suspicion Chain" of FOMO Trading

In a market FOMO state, a collective buying force forms that is almost unavoidable. We can break it down into three similar "suspicion chain" logics:

1. Eliminate the possibility of communication

Market trends change rapidly, and individuals have almost no time for sufficient communication and rational analysis before making decisions. In other words, the market does not allow "civilizations" to sit down and have a good talk.

2. Create a "zero-sum expectation" that as many people as possible agree on

Here, "angle" refers to the investment logic of the event. For example, the profits of early buyers inevitably come at the opportunity cost of later buyers. All rational market participants are aware of this. When everyone knows "the later buyers will definitely lose," the market will form a consensus of "must buy first."

3. Create unbearable opportunity costs

FOMO is effective because the cost of missing out is too high. Watching others become wealthy from this event while hesitating leads to significant psychological torment, even resulting in devastating physical and mental harm. Ultimately, the majority in the market will be forced to buy in, even going all in.

These three factors work together to form the "positive suspicion chain" in a FOMO state. Its "positivity" lies in the fact that it compels market participants to take the "buy" action that aligns with the designed purpose, and it is inevitable.

Case Study: Market Sentiment on the Day of $TRUMP Launch

Taking the day of the $TRUMP token issuance as an example, here’s how this "positive suspicion chain" drives the market:

When the news of Trump launching a coin broke, the market immediately surged, and the market cap skyrocketed. Although some doubted the authenticity of the news, the market reacted so quickly that there was no time to verify.

After a simple verification confirmed it was not a hack, the market concluded: "External funds will definitely buy," which is an irreversible trading logic (angle).

The Earth’s leader personally launching a coin is an extremely rare event; missing it would be a historic loss. The market consensus is: "If you miss out, not only will you lose money, but you might also be ridiculed by your friends for life."

Thus, the vast majority in the market had no choice but to buy in, even going all in.

Factors Determining the Intensity of FOMO Trading

So, how strong is the FOMO effect of an event? It mainly depends on the following three factors:

The speed at which trends form

The faster the market reacts, the less time individuals have for communication and analysis, making trading behavior closer to instinctive reactions.The consensus range on the FOMO trading logic (angle)

Can this "angle" be recognized by the majority of the market? The broader the consensus range, the stronger the FOMO effect.The rarity and non-replicability of the event itself

The more unique and difficult to replicate the event, the stronger the market's perception of "missing it is a lifelong regret," thus driving stronger FOMO buying behavior.The financial strength of the crowd

This is the variable that most people overlook—if the main group spreading FOMO does not have enough funds, the price will quickly collapse.

Pricing Model for Dissemination - Making FOMO Quantifiable

Greatness cannot be planned, but FOMO can.

In the Crypto market, FOMO is a market sentiment that can be engineered, shaped, and even quantified. While "greatness" cannot be planned, the creation of FOMO has traceable patterns.

If you want to create a FOMO, among the three key elements mentioned earlier, the easiest to control is the first point (trend speed). Because the initial surge and market hype are controllable by the project party. The second point (market consensus on the narrative angle) involves finding a widely recognized "high pricing" angle and leveraging the market's cognitive lag (i.e., information spillover leading to lower pricing).

As for the third point (the rarity and non-replicability of the event), this is the hardest to manipulate. Anything that can be planned is, by nature, no longer rare and thus easy to replicate. However, opportunities still exist in the market—if one can exploit the differences in market participants' perceptions of scarcity, FOMO can be created through "pricing gaps."

Case Study: The Evolution of FOMO in Crypto AI Narratives (November 2024 - February 2025)

A typical example is the rapid rise and fall of the Crypto AI narrative. This cycle roughly went through the following stages:

Create an information gap, preventing traders from communicating: VC firms and behind-the-scenes groups used meme coins as vehicles to quickly raise market enthusiasm, forming a fast-paced environment where traders could only passively follow without enough time for rational communication and discussion. If a form other than memecoins, such as mining machine dividend schemes, had been used, this narrative could not have generated FOMO.

Utilize cognitive hierarchy differences to expand the target audience of the "zero-sum angle" narrative from AI professionals to general Crypto investors who perceive AI as the future, further covering ordinary traders who do not truly understand AI but know it is a trend.

Due to the high cognitive threshold of the AI topic outside the Crypto circle, many in the market could only invest in FOMO based on the intuition that "industry leaders are pushing the AI track."

High Replicability Leads to Narrative Cooling

AI, as a technology, has high replicability and does not possess long-term scarcity.

This also explains why the AI narrative only lasted about three months and subsequently cooled down as traditional AI projects like Deepseek gained traction, leveling the market's cognitive gap, leading to the emergence of numerous similar AI trading agents, and the FOMO narrative fading away.

Mathematical Model for Pricing Dissemination

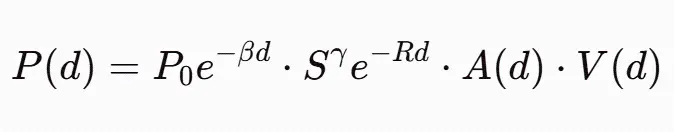

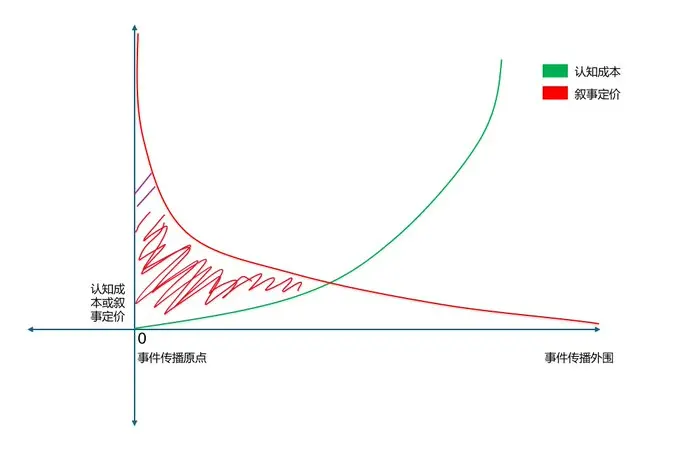

Based on this, we can abstract a mathematical model for the pricing of narrative dissemination, focusing on how the narrative's pricing P(d) changes with the dissemination distance d, simulating a narrative/event/project as it spreads from the initiator outward, from being ignored to becoming a hot topic, from being sought after to being disregarded. Since I graduated from a vocational school, thanks to ChatGPT, if you are like me and illiterate, please jump directly to the summary section:

Where:

P0: Initial pricing at the event's dissemination origin (usually the highest)

e−βd: Trust decay factor, controlling FOMO intensity (the speed at which market trust declines)

Sγ: Scarcity of the event (the scarcer, the slower the pricing decline)

e−Rd: Replicability of the event (the easier to replicate, the faster the pricing decline)

A(d): Attractiveness of the event to different groups

V(d): Crowd value, measuring the financial strength available to different audiences during pricing

Core Variable Explanations

- Trust Decay Factor e−βd

The further the dissemination distance d, the weaker the market's trust in the event, leading to weaker FOMO.

Affected by cognitive cost C(d): the higher the cognitive cost, the harder it is for the market to understand the event, leading to faster trust decline (β increases).

With lower cognitive costs, the event spreads more easily, and FOMO lasts longer (β decreases). - Scarcity Factor Sγ

The scarcer the event, the more the market is willing to maintain a higher price, and the slower the FOMO decline.

If the event is highly scarce (like the $TRUMP coin launch), the narrative pricing can remain high for a certain period.

If the event is not scarce (like the AI narrative), the market will quickly cool down due to increased supply. - Replicability Factor e−Rd

If the event is easy to replicate, the market's enthusiasm will quickly decline.

Highly replicable events (like AI tokens): FOMO only lasts a short while.

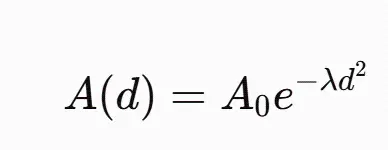

Low replicability events (like Musk's coin launch): narrative pricing declines more slowly. - Audience Attractiveness A(d)

Different groups find different events attractive, determining the spread of FOMO.

Influencing factors: the match between the event and the audience (λ).

The audience's cultural background, market experience, and trading habits; the larger λ is, the lower the match, and the poorer the attractiveness.

This can be modeled using a Gaussian distribution:

If the event cannot attract a broader audience, the spread of FOMO will quickly come to an end.

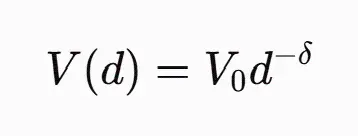

- Crowd Value A(d)

V(d) represents the trading capital strength of the crowd at distance d in the market.

The financial strength of different crowds determines the driving force of FOMO trading: early entrants are usually high-capital traders (institutions, whales), who have a greater impact on prices. Once it spreads to the periphery, it mainly involves retail funds, and the influence weakens.

Assuming a power-law distribution:

Where:

V0 is the initial capital strength at the event's dissemination origin (e.g., VC, whales)

δ is the capital distribution decay factor, controlling the flow direction of market funds:

- A small δ (stable capital flow): the capital strength of the peripheral crowd remains strong.

- A large δ (rapid capital decay): the peripheral crowd mainly consists of small retail investors, making it difficult for FOMO to sustain.

Impact of Crowd Value:

If V(d) declines too quickly, meaning the peripheral crowd consists of small funds, then even if FOMO spreads, the trading influence will not be strong, leading to insufficient price support.

If V(d) declines slowly, meaning there is still strong capital support in the periphery, FOMO trading will last longer.

Summary of the Pricing Model for Dissemination

Although this formula may not be precise, it reveals an eternal market rule:

For any event, the further the dissemination distance, the higher the audience's understanding cost; the further the distance, the lower the price the audience is willing to accept.

Events that are scarce, non-replicable, and targeted at specific audiences see their narrative pricing decline more slowly, while easily replicable and complex information events rapidly depreciate during dissemination.

For the "scythe," the red shadow area represents the best "harvesting zone."

The intersection of the cognitive cost curve and the narrative pricing line represents the death of the narrative.

Real World Attention - The Greatest Common Divisor for Maximizing Pricing Dissemination

We are constantly paying for information:

Supermarket sales, Black Friday discounts

FOMO for meme coins, real estate speculation

Political movements, and even wars

Some costs are monetary, while others are life itself.

This is not a matter of "Degen vs. Normie" or "Ponzi vs. Halal," but rather the underlying logic of the human attention economy.

So, how do we construct a dissemination model with high narrative pricing? What is the greatest common divisor?

This leads to my self-created concept—Real World Attention (RWA).

RWA Definition:

The most valuable narratives must be events that attract attention outside the core high-frequency users in the crypto space while also appealing to a globally average IQ audience with "viral dissemination" potential.

It ensures the broadest audience while also covering those with high trading value.

If you don't believe it, try answering the following questions without looking at the answers:

1. Why do "presidential coins" and "celebrity coins" always have a market, regardless of market conditions?

These events face a globally predictable cognitive group, and the unacceptable cost of missing out creates a positive suspicion chain.

When a president issues a coin: especially the president of a major country, the cognitive audience covered is the widest, so no matter how much it gets exploited, there will always be someone rushing in.

2. Why do many non-American artists struggle when issuing coins?

Audience issue: North American artists have audiences that are often active on crypto platforms (like Twitter), and their information can be directly or indirectly transmitted to the crypto space; while the audience value of non-American artists is relatively low.

The crowd emerging from the dissemination origin has a high cognitive cost, leading to naturally lower pricing.

3. Why do event-based tokens perform better than celebrity coins, even with celebrity involvement? (e.g., $MAGA, $PNUT, $Jailstool, $Vine, etc.)

There are three reasons:

Dramatic tension: The event itself is more attractive, capable of crossing into the crypto space and attracting all onlookers, enhancing the match between the event and different crowds.

Dissemination audience vs. fan base: The dissemination audience is a dynamic process, consisting of those activated by the event and responding; while celebrity fans are a static, fixed value.

Celebrity coin issuance can only activate a small portion of a fixed crowd, while an event can activate a broader group, expanding the dissemination distance.

Scarcity: Events inherently possess scarcity attributes. For example, although Liu Xiaoqing and Mao Amin are similar, Mao Amin was involved in tax evasion, while Liu Xiaoqing found a boyfriend 30 years younger at over 60 years old—such events are both rare and eye-catching.

- Why do many complex AI, DeFi narratives, and intricate funding models struggle to gain traction?

Cognitive costs are too high (β is too large).

In the secondary market, the common cognitive range is too small, leading to low pricing, making it difficult to form a positive suspicion chain, and even effective dissemination is hard to initiate, let alone FOMO. - Why do new coins from major developers and large vehicles trigger FOMO in meme coins?

For the memecoin audience, this is a naturally positive suspicion chain zero-sum scenario.

If you don't get on board, you'll never get on board.

Data and monitoring tools relay information in real-time, requiring no additional cognitive costs for the memecoin audience.

The only issue is that once it spreads to the outer circle, the outer audience may judge themselves to be on the periphery and choose not to enter. - Why do purely halal and technical narrative VC coins perform so poorly in the secondary market?

Same as 4.

In a sense, Real World Attention (RWA) is even more valuable than Real World Assets, because forming a consensus based on attention is much easier than forming a consensus on assets.

An American might struggle to recognize the asset value of a rural house in Thailand's Sakhon Nakhon Province; however, if a local teenager's TikTok video becomes a meme, an American might resonate with it just the same.

Insights for the Market and Project Leaders

The era of relying on a narrative, model, or system to explode has passed. Projects that cannot be recognized by dissemination and market pricing have no chance of "exploding" or "gaining traction."

If a project cannot be recognized by dissemination and market pricing, it will never have the opportunity to "explode" or "gain traction."

Even the most battle-hardened ground promotion teams will struggle to succeed if they "lack an angle."

Conversely, an ordinary project can inexplicably explode if it can trigger real-world attention.

When launching, you need to plan dissemination like this:

Set boundaries: If the main system of the project cannot meet the dissemination model, designate a portion specifically for dissemination to ensure it does not affect the main system.

Set the system: Use assets like meme or NFT that can rapidly increase in value and do not allow time for communication;

Or adopt incremental pricing mutual assistance models (like VDS, Taishan crowdfunding, Fomo3D).

Choose an angle: According to RWA logic, select narratives with low information complexity and broad audience coverage.

Create events: Generate events with dramatic tension as a vehicle for dissemination, designing the entry of funds as a real-world attention event (e.g., "An octogenarian unexpectedly wins millions" or "TST dev addresses join forces to dominate the BSC").

Taking @ethsign as an example:

The narrative of EthSign itself is of a type that is very difficult to promote: B2B/B2G applications:

- Token Table token distribution platform

- A crypto alternative to Docusign

- Digital identity

From the perspective of retail investors, especially young retail investors, the entire project screams one word: boring.

@realyanxin cleverly designed a "Orange Dynasty" (sounds like a Northeast bathhouse) theme for the B2C end.

To create dissemination and form a positive suspicion chain, Sign chose to launch an NFT and an airdrop event as vehicles. The airdrop also selected an absolute black box mechanism that cannot be farmed, minimizing the possibility of communication.

Through a $16 million financing announcement + Binance Labs investment + a large number of KOLs wearing orange glasses to join and adding elements of viral dissemination + engaging in community cult activities, the entire project's B2C messaging collapsed into a meme, maximizing the audience match in the crypto space and lowering cognitive costs.

The covered crypto KOLs are also relatively high-value trading groups.

This is already the optimal solution available for this type of non-B2C project. Even with all these designs, Sign still needs to invest a lot of manpower in high-intensity community activities and education to artificially enhance audience matching, lower the cognitive costs of peripheral crowds, and maximize dissemination distance. Fortunately, the Sign team has a group of event marketing talents who can truly capture attention during execution.

If you are a traditional CX project:

Your event dissemination core is all about community leaders. Covering KOLs in the crypto space may require an excellent agency to schedule calls in two days.

However, CX community leaders, regardless of how familiar the relationship is, generally need to meet offline, give a lecture, and then treat them to a meal before they can start disseminating and generating funds. Even the most inner circle has a high cognitive cost (β is large). When community leaders then disseminate to their own downline, this process has to be repeated.

In an era where young people no longer hold "systems and organizations" in high regard, this method incurs higher costs for external dissemination. This means more educational resources must be invested, raising the cost of starting dissemination from the origin, creating a vicious cycle of dissemination.

So what you need to do is:

Reduce the complexity of the model and narrative, keeping it within the scope of three sentences: What is it? How to play? How to manage risks?

Design a zero-sum scenario that requires no explanation to establish FOMO. This scenario is primarily for dissemination and can be an independent complete product or an entry point designed for a larger project.

Design the entry of funds as a real-world attention event. For example, "An octogenarian is dragged by her grandson to play a game and unexpectedly wins millions, leading to a courtroom battle with her greedy grandson" or "TST dev addresses join forces to dominate the BSC."

If you are purely a meme dev or meme infrastructure…

Here, "meme" refers to any type of low liquidity asset that is launched on-chain without permission, with no mechanisms favoring chip distribution, and without human intervention in price discovery.

"Dev" or "infrastructure" refers to the initiators related to the launch of this type of asset.

According to the dissemination pricing model and positive suspicion chain, there are only three truly useful resources:

On-chain active market makers: those who understand how to control the rhythm and manage the supply for rapid trading.

Network promoters: like Connor Gaydos of Enron Coin, Abbey Desmond who turned Gatwick Airport into Luton Airport, or the event planners behind China's "Guo Meimei" and "Feng Jie" incidents—these individuals can truly stir real-world attention.

Precise trading KOLs and widely covered public media/KOLs: they can activate broad market consensus.

Other traditional "fundamental narratives" in the crypto space are basically unimportant—they do not rely on them for dissemination, but rather sell a story to exchanges, market makers, and industry influencers.

In Conclusion

I have come to realize that any model I put out will become a popular topic, raising the competitive threshold within the circle. However, I am truly fed up with a large number of project parties who come up with a narrative out of thin air and then seek my advice (flattery). Another purpose of this article is to hope that project parties can thoroughly read and understand this before scheduling a call with me.

If you are not a project party but rather a KOL wannabe striving to build a personal brand, keep going and continuously create events to stir attention. This was actually the main point that made me recognize @EnHeng456 and @Elizabethofyou: they are really good at creating events that attract attention. This is a very rare ability. With more practice, you too can create your own "Enron."

Nobility and commoners, is there really a difference?

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。