Original author: Eric SJ (X: @sjbtc9)

"We embrace Bitcoin because it saved the world economy from inflation, yet in Web3, we are practicing what we oppose: a disguised form of inflation through timed unlocks."

The theme of this article will horizontally explore the phenomenon of "low circulation and high FDV" and the improvement of the "fair launch" paradigm regarding token issuance.

Before this:

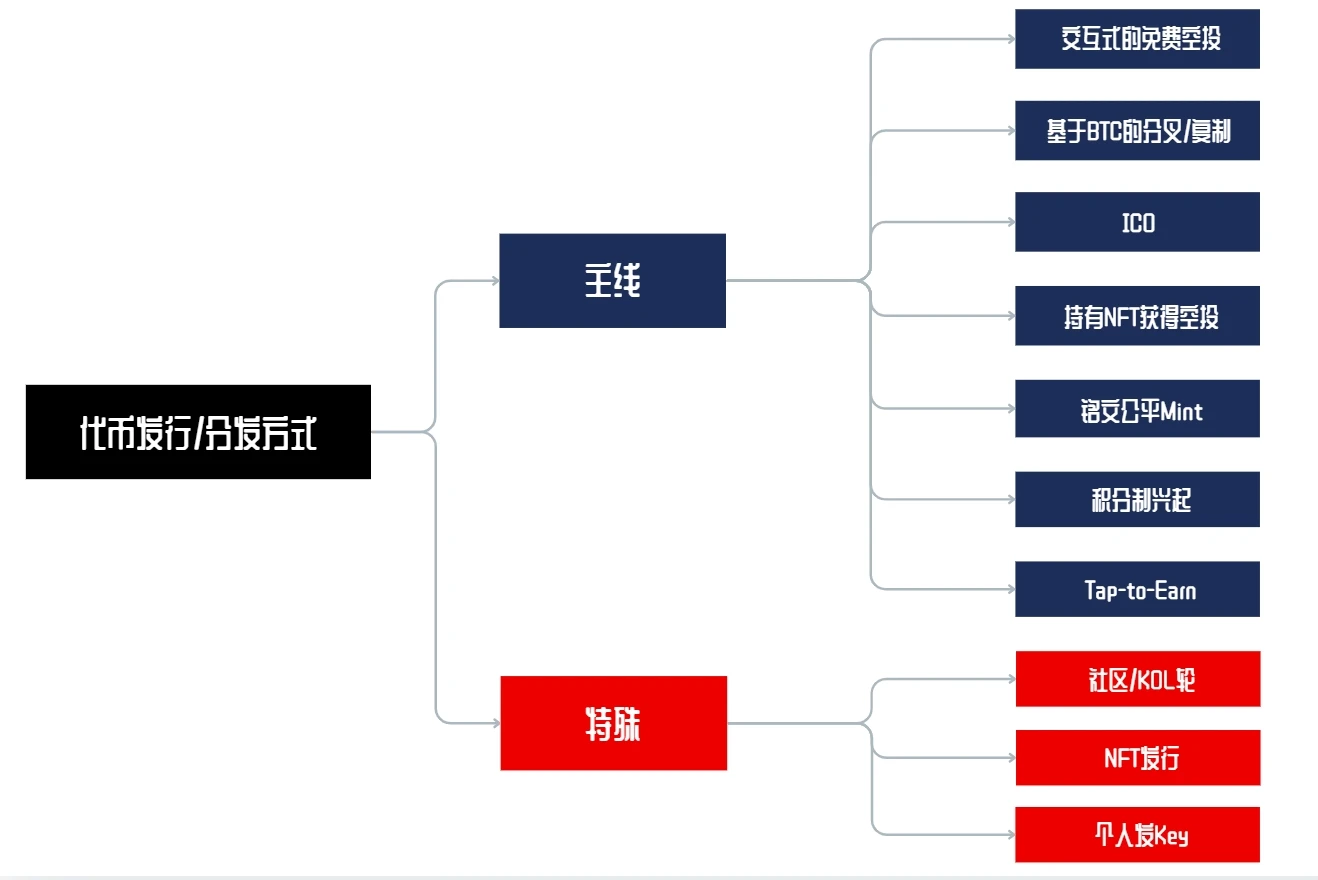

I have previously outlined the transformation routes of token distribution methods over the years, from free airdrops to the recently emerged Tap to Earn. Friends interested in this can jump back to read.

### 1. The Essential Problem of "Low Circulation and High FDV"

Even though I have previously published related reports in Chinese, looking back now, I have not truly explored the essence of the problem. The correct question to ask is:

Why is there a gap between market capitalization and FDV? And why is this a problem?

Looking back at traditional financial markets, this seems to be a unique feature of Web3. Although there are differences between total share capital market value and circulating market value in traditional financial markets, they are not very large and this phenomenon is not widespread. However, this phenomenon is prevalent among the VC tokens we are familiar with this year.

(Most initial circulations are controlled to be within 20%.)

Even if there are new stock issuances in securities later on, they are usually conducted through financing or stock splits, both of which are immediately reflected in market prices.

The fundamental difference between the two markets stems from culture, which is a problem that has existed since the design of Bitcoin: a fixed supply in advance allows the market supply and demand to coincide with the issuance curve. If we apply this phenomenon to traditional financial markets, FDV = all possible future issuances of stocks.

Therefore, whether the FDV metric has practical significance, in my view, it does not. Thus, I @sjbtc9 only consider circulating market value as the current reference metric, rather than FDV.

However, before a project's official TGE, this metric is very important for the fundraising stage. How to slice the cake while reasonably financing during the distribution of interests among various parties is crucial for a project. Therefore, returning to the first question:

Essentially, the difference between circulating market value and FDV arises from the transition between primary and secondary markets.

But this is not the root cause of the market's criticism; after all, the primary market provides a very high trial-and-error space for the industry's development. What truly causes this phenomenon to become problematic is precisely the corresponding: the time-based unlocking issue.

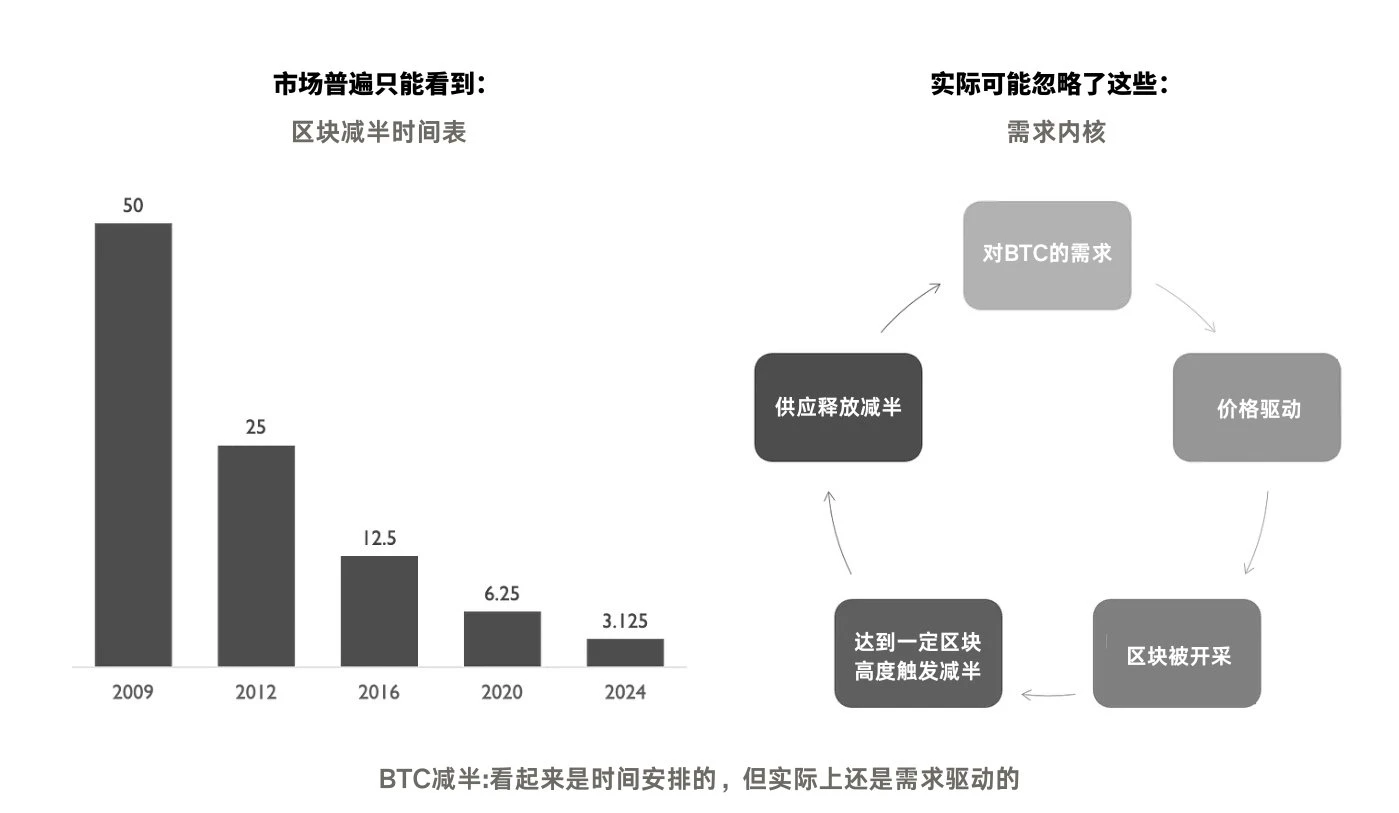

The model itself is not the problem; how it is adopted is. After all, Bitcoin also started with low circulation, but while most projects imitate Bitcoin's limited total supply and low initial circulation, they fail to adopt its core principle: demand-driven issuance rather than time-based issuance.

The relationship between Bitcoin's issuance and price is often misunderstood as purely time-based (thanks to the well-known "four-year halving cycle"), but in reality, it is also driven by demand factors. Even all mined coins are based on this logic: if upstream miners cannot profit in the market in the long term, they will leave this node group.

This demand-driven issuance aligns with basic economic principles: only when supply and demand are formed can prices be established; for an L1 protocol, only when this supply and demand are formed can security be maintained.

In stark contrast, most crypto projects (especially those supported by venture capital) only follow time-based issuance without the market supply and demand aspect, which is the real issue of "low circulation, high FDV."

In addition, there is a more hidden problem: misalignment of interests.

Most projects have different issuance arrangements for teams, venture capital, communities, and treasuries.

Although it seems that certain "vulnerable groups" (such as communities) are prioritized during issuance, with their tokens unlocked first, this can lead to conflicts of interest, reflecting extremely poor design.

The following are typical manifestations of this situation:

(1) Before unlocking, the community/market expects token sell-offs, so they often act according to this expectation to avoid further losses. This is also a major starting point for what the "haircut army" refers to: selling off to always profit;

(2) After the project team reaches the unlocking period, they artificially inflate the token price by creating news and market-making to attract retail investors, then sell the tokens to them;

This misalignment leads to opposition between the team and VC and the community, undermining trust and causing many VC-supported tokens to perform poorly after TGE.

Therefore, demand-driven token issuance has become a potentially more reliable solution.

### 2. Demand-Driven Unlocking

For projects with a fixed total supply and low circulation issuance, an economically reasonable solution is to base issuance on demand rather than time (this is especially applicable to VC-supported projects with vesting mechanisms).

This will bring two market effects:

(1) Supply and Demand Balance: Tokens will only be released when there is additional demand (e.g., token consumption), thus preventing planned inflation;

(2) Aligned Interests: Unlocking will only be triggered when the community/market generates additional demand for the token (e.g., protocol usage), putting the team and venture capital on the same boat as the community.

However, this also brings new risks: the vesting of the team and venture capital is uncertain. If the community stops participating, demand will fade, and no new tokens will be unlocked.

But shouldn't this risk be borne by the team and venture capital? Without it, Web3 will still be a zero-sum game between insiders and the community—or worse, a financial scam.

### 3. Three Models Based on Demand Unlocking

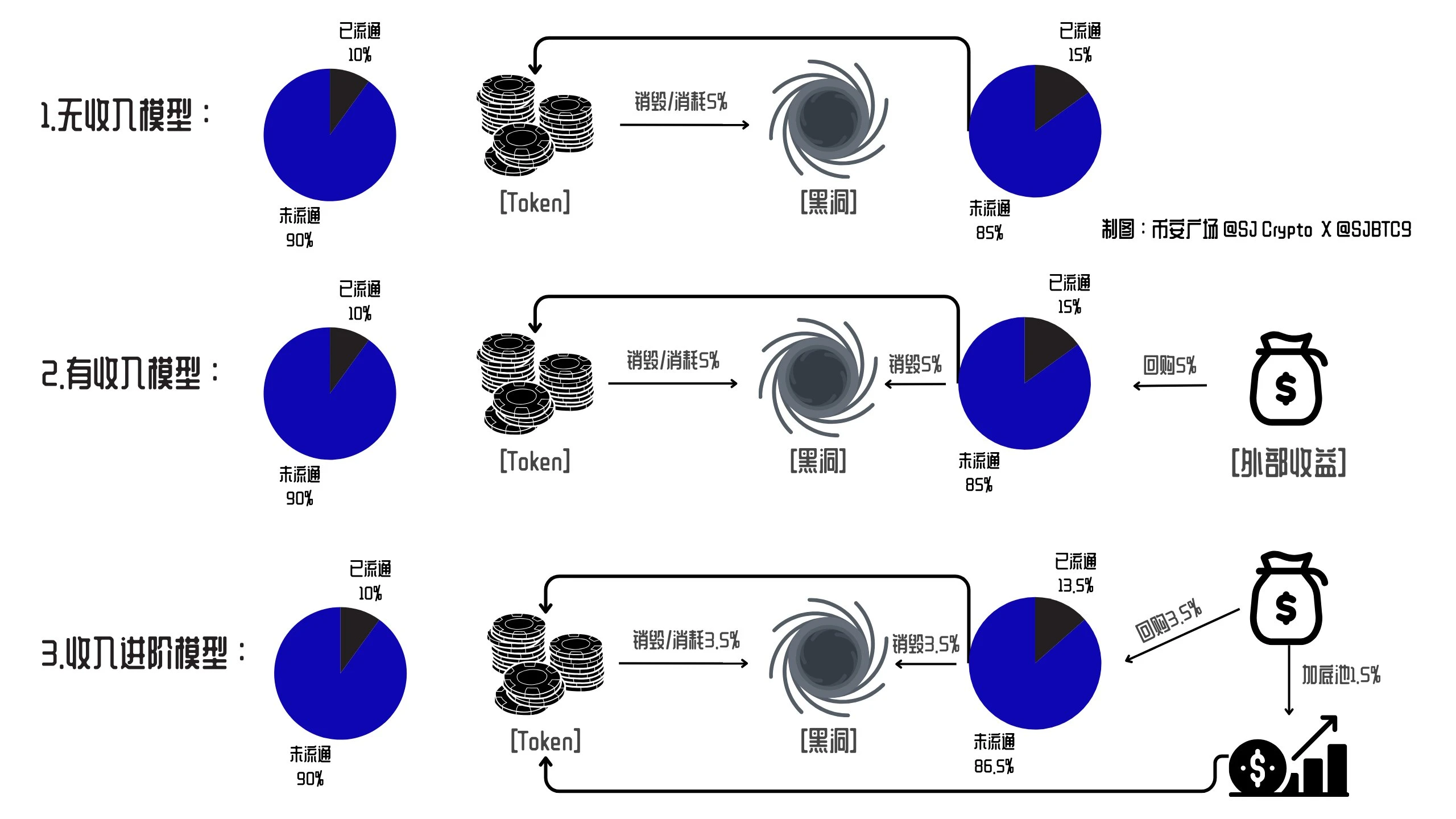

Based on the aforementioned phenomena and conclusions, this article presents three token launch methods centered around the supply-demand model, with a core focus on fair launches, just with different income models:

- I assume a common scenario of initial low circulation (10%) with a large portion belonging to the community.

(1) No Income Model: Suppose the token has no income model, but whenever the circulating tokens in the market are consumed and destroyed, an equal amount of new tokens will be released (proportionally distributed to the team/venture capital/community/treasury, etc.), maintaining the circulating supply until the final release.

This design can be simply summarized as driving the unlocking of new tokens through destruction or consumption. However, this design essentially dilutes the community's share in the circulating supply with each round of release until the community's share becomes smaller than other parts.

Even so, this version is still more reasonable than a completely time-based unlocking.

(2) Income Model: This model requires the project itself to have income beyond the token itself, such as some cross-chain bridges, DEXs, Pump, and other DeFi protocols. This model builds on the "No Income Model" by using the protocol's own income to purchase and destroy newly issued shares, thus ensuring the stability of the market circulation.

Under the mutually offsetting effects, it aims to minimize the impact on market prices and circulation, making the overall pool more stable. In this model's design, the community's major share can be retained to the greatest extent without harming the interests of other parties.

(3) Income Model Plus Version: This is based on the second version, dividing the protocol's income into two parts: one part is still used to hedge against the impact of unlocking, while the other part is used to inject liquidity into the token's liquidity pool.

Ideally, this will create a positive flywheel effect in the token's basic model design until all unlocks are completed while ensuring a certain stability in token prices.

Compared to the previous model, this requires more precise mathematical calculations: setting the optimal unlocking ratio between destruction and issuance and determining the ideal income distribution—ensuring that part of it is used for inflation buybacks while the rest is effectively injected into the pool.

The designs of the three models above essentially stem from binding the unlocking of tokens with the interests of all parties, transforming the original misalignment into a demand-driven unity.

Currently, we can see many projects incorporating income, destruction, and buybacks into the token economy, but there is no design that binds market demand with token unlocking for high FDV.

### 4. Theoretical Examples

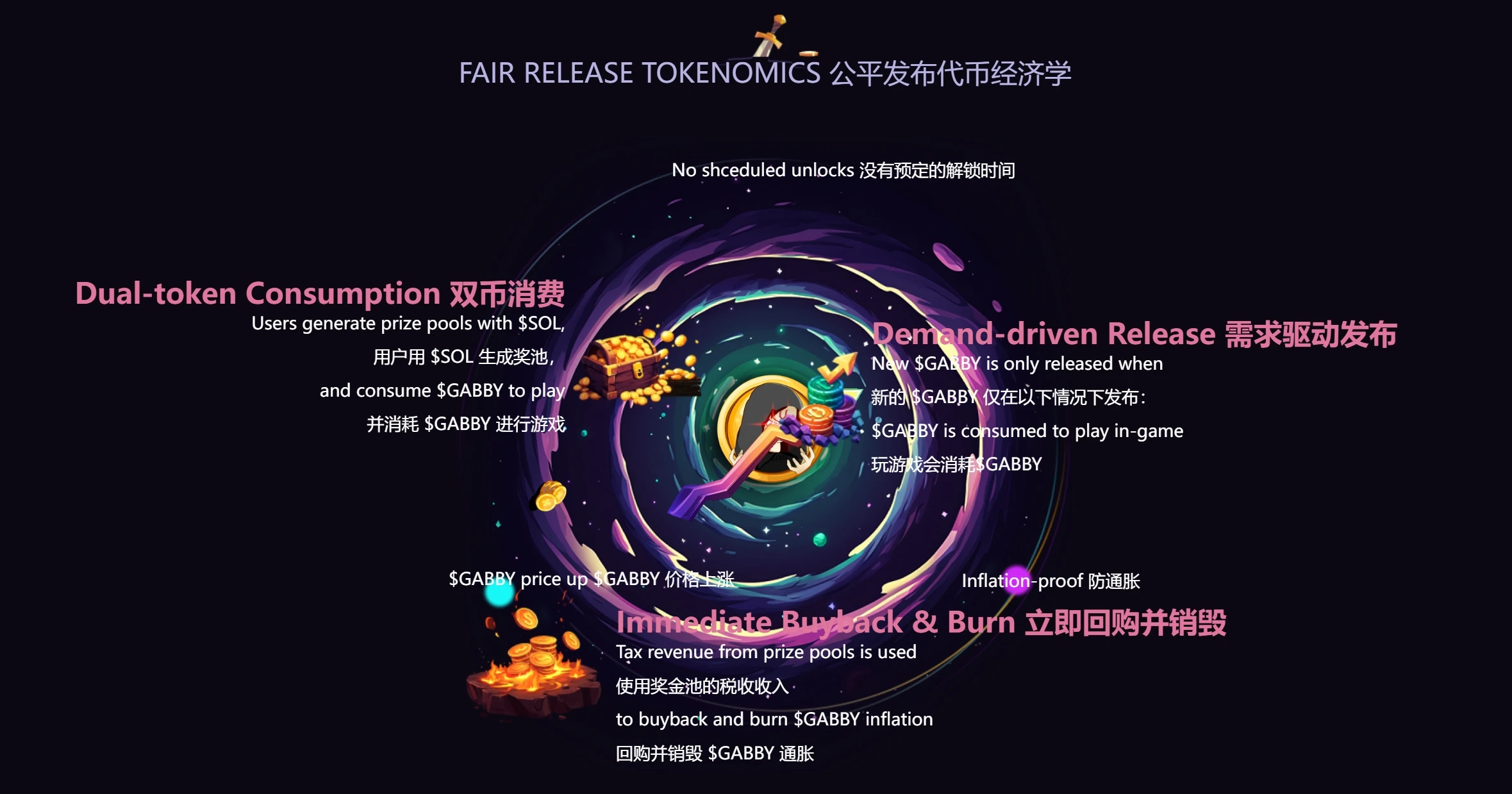

In fact, most of the viewpoints in this article come from a tweet by @gabbyworld, the founder.

I have translated and modified the issues and models mentioned therein, hoping to help you understand the underlying economic design thinking and the rationale behind this design.

This design has also been applied to the token design of their project itself.

From my perspective, I believe that unlocking future tokens based on supply and demand is a very bold and difficult attempt, because for the project side, the primary task is to persuade its investors to accept this.

I work in VC myself, and to be honest, it is very difficult for us to accept this.

While many attribute the poor performance of the crypto market to liquidity shortages, stagnation of innovation, or narrative fatigue, few realize that the real problem lies in unfair wealth redistribution, which further exacerbates the divide between institutions and the community, and is also the reason why the current Meme craze continues.

I am not sure how the GabbyWorld team coordinates this, but amidst what I see as somewhat idealistic designs, they have also begun to execute it, which is not easy.

Regarding the fair launch of the inscription market, I have previously stated that a completely community-driven approach is not feasible, as it incurs very high decision-making costs in business development.

The method Gabby uses to drive unlocking through the supply and demand of the token itself is also difficult for other projects to replicate. If this can be successfully implemented, it would be entirely worth creating a separate category in the issuance history classification I initially posted.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。