Original Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translation by|Odaily Planet Daily (@OdailyChina)

Translator|CryptoLeo (@LeoAndCrypto)

The U.S. elections have propelled the prediction market Polymarket to further popularity, with those seeking profit starting to place bets, while those looking for outcomes use it as a news data platform to gather information. As a "breakout" blockchain application, Polymarket effectively combines on-chain funds with real-world predictions. Vitalik has repeatedly praised Polymarket in his writings and is also a loyal fan of the early prediction market Augur. Today, Vitalik published an article discussing "information finance" through the lens of prediction markets. Below is the full content, translated by Odaily Planet Daily:

One of the Ethereum applications that excites me the most is prediction markets. I wrote an article about futarchy in 2014, which is a governance model based on predictions proposed by Robin Hanson. As early as 2015, I was an active user and supporter of the prediction market Augur, and I made $58,000 betting on the 2020 elections. This year, I have been a loyal supporter and follower of Polymarket.

For many people, prediction markets are about betting on elections, and betting on elections is gambling—if it can help the public enjoy some fun, that would be great, but fundamentally, it is not more interesting than randomly buying memes on pump.fun. From this perspective, my excitement about prediction markets may seem puzzling. So in this article, I will explain the concepts that interest me about prediction markets. In short, I believe:

The existing prediction markets are a very useful tool for the world;

Furthermore, prediction markets are merely pioneers in a more popular field, with the potential to be applied to social media, science, news, governance, and other areas, which I will categorize as "information finance."

The Dual Nature of Polymarket: A Betting Site for Participants, a News Site for Everyone Else

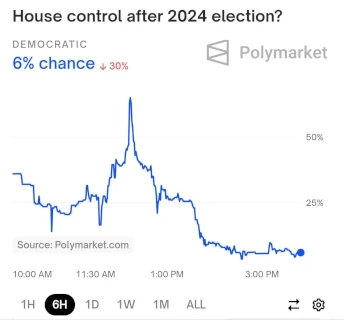

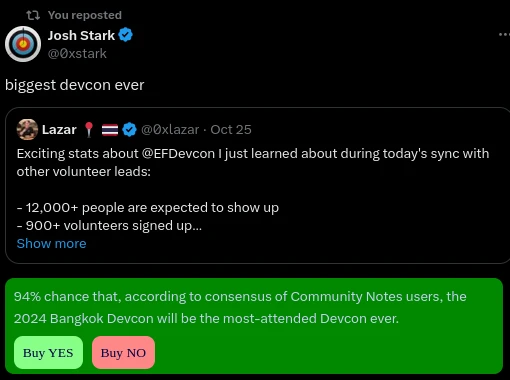

In the past week, Polymarket has been a very effective source of information regarding the U.S. elections. Polymarket not only predicted a 60/40 chance of Trump winning (while other sources predicted 50/50, which is not particularly impressive), but it also showcased other advantages: when the results came out, despite many experts and news sources trying to lead the audience to hear favorable news for Harris, Polymarket directly revealed the truth: the chance of Trump winning exceeded 95%, while the chance of taking control of all government departments exceeded 90%.

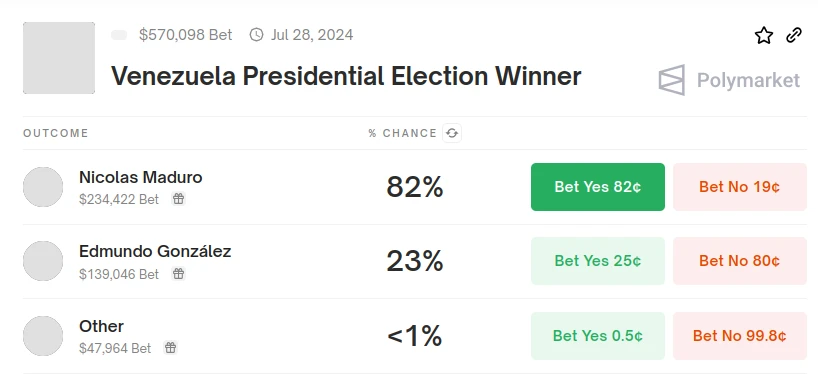

But for me, this is not even the best example of what makes Polymarket interesting. So let's look at another example: during the Venezuelan presidential elections in July, the day after the election, I accidentally saw someone protesting against the highly manipulated presidential election in Venezuela. At first, I didn't pay much attention. I knew Maduro was one of those "basically dictators," so I thought he would certainly falsify every election result to maintain his power, and there would be protests that would fail. Unfortunately, many others failed as well. Later, while browsing Polymarket, I saw this:

People were willing to bet over $100,000 on the possibility of Maduro being overthrown in this Venezuelan election at 23%, and now I took notice of this matter.

Of course, we still knew that the outcome of being overthrown was unlikely. Ultimately, Maduro remained in power. But the market made me realize that this attempt to overthrow Maduro was serious. There were large-scale protests at the time, and the opposition unexpectedly adopted well-executed strategies to demonstrate the fraudulent nature of the election to the world. If I hadn't received the initial signal from Polymarket that "this time, something needs attention," I wouldn't have started paying so much attention.

You shouldn't completely trust the charts: If everyone believes the charts, then any wealthy person can manipulate the charts, and no one would dare to bet. On the other hand, completely trusting the news is also a good way. News has sensational motives and exaggerates the consequences of anything for clicks. Sometimes a situation is reasonable, and sometimes it is not. If you see a sensational article and then check the market to find that the probability of the related event hasn't changed at all, then skepticism is warranted. Additionally, if you see an unexpectedly high or low probability for an event in the market, or a sudden change, that is a signal to read the news and see what led to that conclusion.

Conclusion: By reading both news and charts, you can gain more information than by browsing either one alone.

If you are a gambler, you can deposit into Polymarket; for you, it is a betting site. If you are not a gambler, you can read the chart data; for you, it is a news site. You should never completely trust the charts, but I personally have incorporated reading chart data as a step in my information-gathering workflow (alongside traditional media and social media), which helps me acquire more information more effectively.

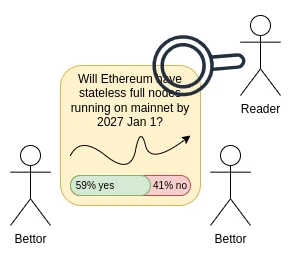

The Broader Concept of Information Finance

Predicting election outcomes is just one use case. The broader concept is that you can use finance as a way to coordinate incentive mechanisms to provide valuable information to the audience. Now, a natural response is: isn't all finance fundamentally related to information? Different participants make different buying and selling decisions because they have different views on what will happen in the future (aside from personal needs like risk preference and hedging), and you can infer a lot about the world by reading market prices.

For me, information finance is like this, but structurally correct, similar to the concept of structural correctness in software engineering. Information finance is a discipline that requires you to:

Start with the facts you want to know;

Then deliberately design a market to optimally obtain that information from market participants.

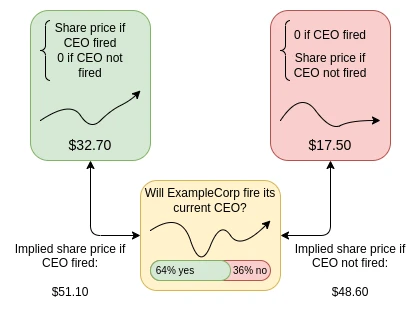

One example is a prediction market: you want to know about something that will happen in the future, so you create a market for people to bet on that event. Another example is a decision market: you want to know whether decision A or decision B will yield better results based on some metric M. To achieve this, you establish a conditional market:

You let people bet on which decision will be chosen: if decision A is chosen, then the value for M is given, otherwise it is zero; if decision B is chosen, then the value for M is given, otherwise it is zero. With these three variables, you can calculate which decision the market believes is more favorable for the value of M.

I expect that in the next decade, artificial intelligence (whether LLMs or some future technologies) will have a huge impact on the financial industry. This is because many applications of information finance are about "micro" issues: mini-markets of millions of decisions, where the impact of individual decisions is relatively low. In practice, low-volume markets often do not operate effectively: for an experienced participant, it makes no sense to spend time doing detailed analysis for a profit of just a few hundred dollars. Many even believe that such markets would not operate at all without subsidies, as there are not enough novice traders to provide experienced traders with profit opportunities, except for the most significant and sensational issues. AI completely changes this equation, meaning that even in markets with a trading volume of $10, we may still obtain relatively high-quality information. Even if subsidies are needed, the scale of subsidies for each issue is also affordable.

Information Finance: Refining Human Judgment

Suppose you have a human judgment mechanism that you trust, and the entire community trusts its legitimacy, but making judgments takes a long time and is costly. However, you want to access a cheap copy of that "expensive mechanism" at least in a cheap and real-time manner. Here are Robin Hanson's thoughts on what you can do: establish a prediction market every time you need to make a decision, predicting what result the expensive mechanism would yield if called. Then the prediction market starts running, and you invest a small amount of money to subsidize the market makers.

99.99% of the time, you won't actually call the expensive mechanism: perhaps you "restore the trade," returning or not returning everyone's invested money, or you look at whether the average price is closer to "yes" or closer to "no" and take that as a basic fact. In 0.01% of cases, perhaps randomly, perhaps in the highest volume market, or perhaps both, you actually run an expensive mechanism and compensate participants based on that.

This provides a credible, neutral, fast, and cheap "refined version," which is a distilled version of the original highly credible but costly mechanism (using the term "refined" as an analogy to LLM model distillation). Over time, this refined mechanism roughly reflects the behavior of the original mechanism, as only participants who help achieve that outcome can profit, while others will incur losses.

This applies not only to social media but also to DAOs. One major issue with DAOs is that there are too many decisions, and most people are unwilling to participate, leading to either widespread use of delegation, which carries the risks of centralization and agency failure common in representative democracy, or being subject to attacks. If actual voting in a DAO occurs infrequently, and most matters are decided by prediction markets, with human and AI combined to predict voting outcomes, then such a DAO could operate very well.

As we saw in the example of decision markets, information finance contains many potential pathways to solve important issues in decentralized governance, with the key being the balance between market and non-market: the market is the "engine," while other non-financial trust mechanisms serve as the "steering wheel."

Other Use Cases of Information Finance

Personal tokens—many projects like Bitclout (now known as deso) and friend.tech that create tokens for individuals and make them easy to speculate on—are a category I refer to as "primitive information finance." They deliberately create market prices for specific variables (i.e., expectations of a person's future status), but the exact information revealed by the prices is too vague and susceptible to reflexivity and bubble dynamics (Note from Odaily Planet Daily: price surges attract buying). It is possible to create improved versions of such protocols and address important issues like talent discovery by more carefully considering the economic design of the tokens (especially where their ultimate value comes from). Robin Hanson's views in "The Future of Reputation" represent a possible end state.

Advertising—the ultimate "expensive but trustworthy signal" is whether you will buy a product. Information finance based on that signal can help people determine what to purchase.

Scientific peer review—the scientific community has long faced a "replication crisis," where certain well-known results have become part of common wisdom but cannot be reproduced in new studies. We can attempt to identify results that need to be re-examined through prediction markets. Before re-examination, such markets would also allow readers to quickly estimate how much they should trust any particular result. Experiments of this idea have been conducted and seem to have been successful so far.

Public goods funding—one of the main issues with public goods funding mechanisms used in Ethereum is their "popularity contest" nature. To gain recognition, each contributor needs to run their own marketing operation on social media, making it difficult for those who lack the capacity to do so or those who inherently have more "background" roles to secure significant funding. An attractive solution is to try to track the entire dependency graph: for each positive outcome, which project contributed how much to it, and then for each project, which project contributed how much, and so on. The main challenge of this design is to figure out the weights of the edges to make it resistant to manipulation. After all, such manipulation has been occurring. A refined human judgment mechanism may help.

Conclusion

These ideas have been theorized for a long time: the earliest works on prediction markets and even decision markets date back decades, and financial theories stating similar things are even older. However, I believe that the next decade presents a significant opportunity for information finance for several key reasons:

Information finance addresses the actual trust issues people face. A common problem of this era is the lack of recognition of who is trustworthy in political, scientific, and business contexts (worse yet, the lack of consensus), and information finance applications can be part of the solution;

We now have scalable blockchains as a foundation, which until recently were unable to truly realize these ideas due to high costs. But now, costs are no longer prohibitive.

Artificial intelligence as a participant makes it relatively difficult for information finance to function when it must rely on human participation to solve each problem. AI greatly improves this situation, enabling effective markets to be established even for small-scale issues. Many markets may have a combination of AI and human participation, especially when the volume of specific issues suddenly increases from small to large.

To fully capitalize on this opportunity, it is time to explore what financial information can bring us through election predictions.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。