Original author: sam.frax, Founder of Frax Finance

Original translation: zhouzhou, BlockBeats

Editor's note: This article explores the differences between digital commodities (such as L1 tokens) and quasi-equity tokens, proposing a new framework for evaluating digital assets, particularly regarding the value of ETH. The author argues that ETH should be viewed as a sovereign commodity rather than a quasi-equity token, as commodities do not generate cash flow or dividends. It also discusses how to eliminate the ambiguous definition of ETH assets, reaffirms the importance of commodity premiums, and points out potential future valuation errors.

The following is the original content (reorganized for readability):

In the cryptocurrency space, I propose a completely new system for evaluating digital commodities, such as L1 tokens, and the distinction between sovereign commodities and governance/equity tokens. This perspective is crucial for ETH and various L2 tokens and may help eliminate the ambiguity surrounding ETH assets.

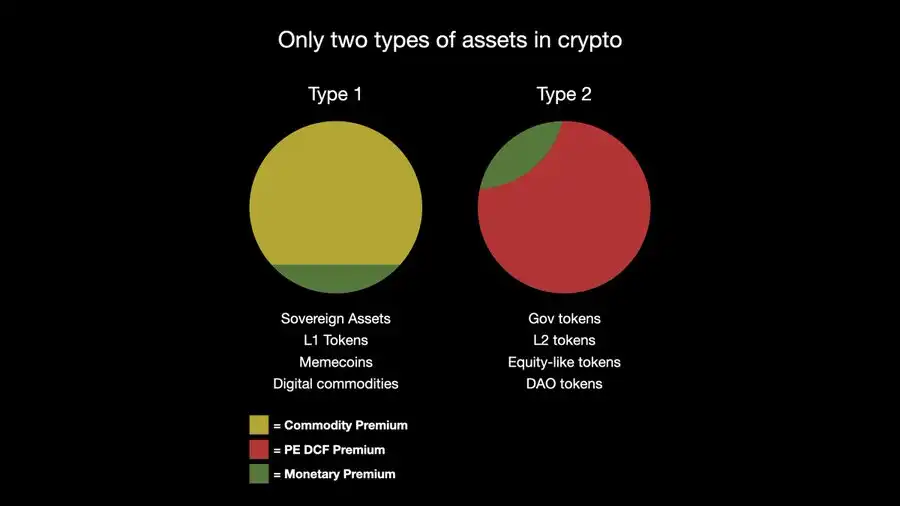

In cryptocurrency, there are essentially only two types of tokens: digital commodities (typically L1 sovereign assets) and quasi-equity governance tokens. I have elaborated on this in previous discussions.

By definition, commodities cannot pay "dividends" or have "cash flow," so if an asset is indeed a digital commodity rather than a governance/quasi-equity token, we must discard this erroneous evaluation standard. Just as a sovereign nation cannot meaningfully default on debt denominated in its own currency (only inflation can occur, not default), digital commodities do not have a real issuer; they are a scarce sovereign asset. Therefore, if it is indeed a commodity, it cannot meaningfully provide dividends or cash flow.

The asset itself is the product, like BTC. Labor and other tangible products can only generate economic demand for commodities.

Ethereum (network + chain) is currently the largest digital nation, a sovereign economy filled with global laborers and builders' innovations. This labor is tokenized in the form of governance/quasi-equity tokens, which are distinctly different from quasi-digital commodities like BTC, ETH, and SOL. Wherever an entity pays holders of digital commodities for any operation, whether liquidity provision rewards, DeFi incentives, or LSD and LRT, these can be measured through experience.

This metric should be defined as the commodity premium of the asset, rather than monetary premium, sovereign premium, or speculative premium, which is a legitimate and fundamentals-based evaluation term for a class of assets.

In the global economy, wherever someone pays another in the form of labor or quasi-equity tokens to hold some form of sovereign asset, we can trace the flow of labor's value to digital commodities. This demand is paid to all forms of ETH holders globally, including those using it in liquidity pools, re-staking, L2, and future DeFi innovations yet to emerge.

This is the global economic demand for commodities, namely the commodity premium. Clearly, this has a far greater effect on the price and market value accumulation of sovereign assets than any PE DCF framework. This is also why BTC's market cap is close to $200 billion without any gas consumption. But in my framework, note that there is no PE DCF premium within a class of tokens, as this is simply not possible.

Only quasi-equity tokens can have cash flow; what we perceive as "dividends/buybacks/burns" within a class of assets is actually just the commodity premium. Similarly, there is no commodity premium within quasi-equity tokens.

This leads to the 1559 burning mechanism, often seen as the core value accumulation mechanism for ETH, as it is considered "the enterprise of Ethereum" paying dividends/cash flow to ETH commodity holders.

But this is an absurd concept because commodities cannot generate cash flow. If a company uses gold in a new industrial application, thereby altering the molecular structure of gold and causing this element to permanently exit circulation, we would not start performing PE or DCF cash flow analyses on gold; we would simply recognize it has a new high-demand industrial use that consumes the commodity. No one would perform PE or DCF analyses on gold.

Similarly, no one performs PE or DCF analyses on BTC. It exists like gold but in digital form. PE DCF premiums are not within the socially acceptable range for real or digital commodities. Furthermore, the 1559 burning mechanism originates from user demand within Ethereum and its L2 sovereign economy. This is merely another economic demand for the $ETH sovereign asset, representing another industrial use case. This demand is paid through the Ethereum blockchain protocol itself, not through labor or manually distributed governance/equity token rewards.

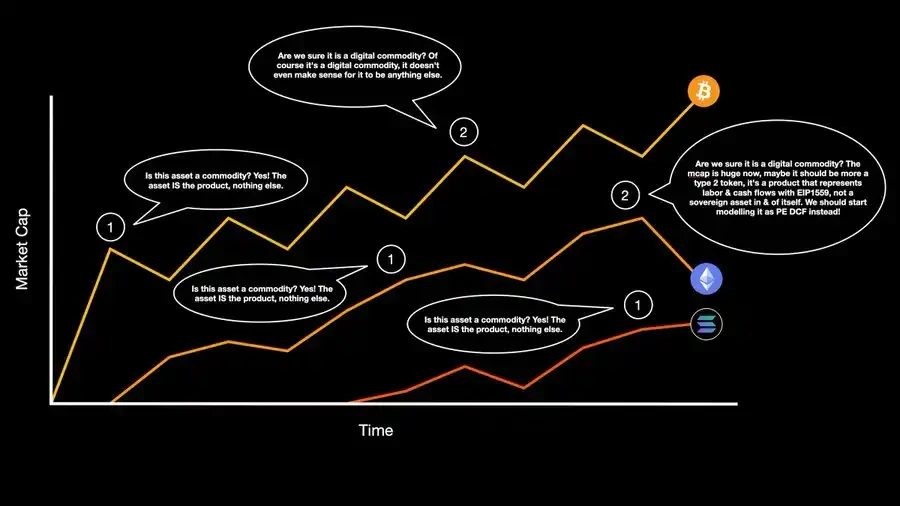

Ethereum is the first project facing the "final boss" challenge in defining its social identity, but SOL is also next, and once it reaches this stage, it may struggle at this step as well. Other sovereign assets will face similar issues as they mature to these stages.

My view on the lifecycle of digital commodities and their related pitfalls is illustrated in a chart. $SOL has not yet reached the second stage, noting that in my view, $BTC and $ETH took different turns at the second stage.

For $ETH, it is crucial to establish this social contract now to show the world before it is too late that it is not just $BTC that possesses this privilege. In fact, this is not a privilege but a social contract of commodity premium—a very specific, quantifiable, rules-based system.

Note that I do not mention the vaguely defined "speculative premium" in the paper. This is because I focus on a well-defined and measurable framework for fundamental value. Speculative premium merely attempts to quantify trading activity based on a future fundamental value system. Speculative premium is not a fundamental framework like commodity premium or PE DCF premium. Speculative premium is merely market activity attempting to calculate how that asset will be valued in the distant future.

Until now, PE DCF has been the only fundamentals-based framework for discussing digital assets, aside from $BTC. It has been incorrectly applied to all assets (except BTC) but should only be used to evaluate assets representing labor, products, and governance rights, not sovereign digital commodities.

In the next part of this series, I will explain how and why certain technical steps, such as determining gas tokens, supply sovereignty, and consensus, are necessary conditions for establishing a social contract of commodity premium. If $ETH can inadvertently and gradually transform into a second-class token, it is also possible to transform a second-class token into a first-class token, but this is a very difficult and sensitive process that is prone to error.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。