Original Title: How to Launch a Crypto Hedge Fund

Original Author: L1 Digital

Original Translation: 0x26, BlockBeats

This article aims to provide guidance and reference for launching an institutional-level crypto hedge fund ("Crypto HFs") from an operational perspective. Our goal is to assist teams planning such launches and serve as a resource in their journey.

Cryptocurrency remains an emerging asset class, and its service infrastructure is similarly nascent. The goal of establishing a robust operational framework is to ensure the security and control of fund assets from both a technical and legal standpoint while facilitating trading and investment, and providing appropriate accounting treatment for all investors.

The information and viewpoints contained in this article draw from L1D's experience as one of the most active investors in crypto hedge funds since 2018, as well as our team's long-term performance investing in hedge funds across multiple financial crises prior to our own launch in 2018. As active allocators of assets in the years leading up to the 2008 global financial crisis and as investors and liquidators in its aftermath, our team has gleaned many lessons that we apply to investments in crypto hedge funds.

As a guide and reference, this article is lengthy and delves into multiple topics. The level of detail given to any specific topic is based on our experience with new managers, who often have less understanding of these topics, which are frequently left to legal advisors, auditors, fund administrators, and compliance experts. Our aim is to help newly launched managers navigate this space and collaborate with these expert resources.

The service providers mentioned in this article are included based on their established brand characteristics and our experience working with them. No service provider has been intentionally excluded from this article. The crypto space is fortunate to have many high-quality service providers that have created a robust and evolving infrastructure, giving newly launched managers many options. This article does not specifically focus on a comprehensive review of the available infrastructure in the field, as other publications cover this well.

The goal here is to examine processes and workflows in detail, identify operational risks, and propose best practices for managing risks in the context of launching and operating a crypto hedge fund. This article will include the following content:

1. Planning and Strategic Considerations

2. Fund Structure, Terms, and Investors

3. Operational Stack

4. Trading Venues and Counterparty Risk Management

5. Financial Management — Fiat and Stablecoins

6. Custody

7. Service Providers

8. Compliance, Policies, and Procedures

9. Systems

Certain sections include case studies of specific crypto hedge funds that failed or nearly failed due to operational reasons covered in this guide. These cases are included to illustrate how even seemingly minor operational details can have significant negative impacts. In most cases, the managers' intentions were to do right by their investors, but their oversights led to consequences they could not fully anticipate. We hope that newly launched managers can avoid these pitfalls.

Investors and investment managers from traditional finance (TradFi) entering the crypto space should recognize the differences and similarities in managing funds in these different environments. This article leverages operations in traditional finance to introduce these differences and how resources available to crypto hedge funds can be utilized to achieve an operational model that appropriately serves institutional investors.

Planning and Strategic Considerations

Identifying and vetting suitable partners, establishing, testing, and refining pre-launch procedures can take months. Contrary to popular belief, from a compliance perspective, institutional-level crypto investing is not a "wild west"; in fact, it is quite the opposite. High-quality service providers and counterparties are very risk-averse and typically have cumbersome and comprehensive onboarding processes (KYC and AML). Such planning also includes considering redundancies in areas such as banking partners. Based on experience, setting up a typical fund can take 6 to 12 months. It is not uncommon to launch in phases, as the full scope of certain strategies may not be achievable on day one, gradually expanding to new assets. This also means that investment managers must consider a certain cost burden when preparing for launch, as revenue takes longer to realize.

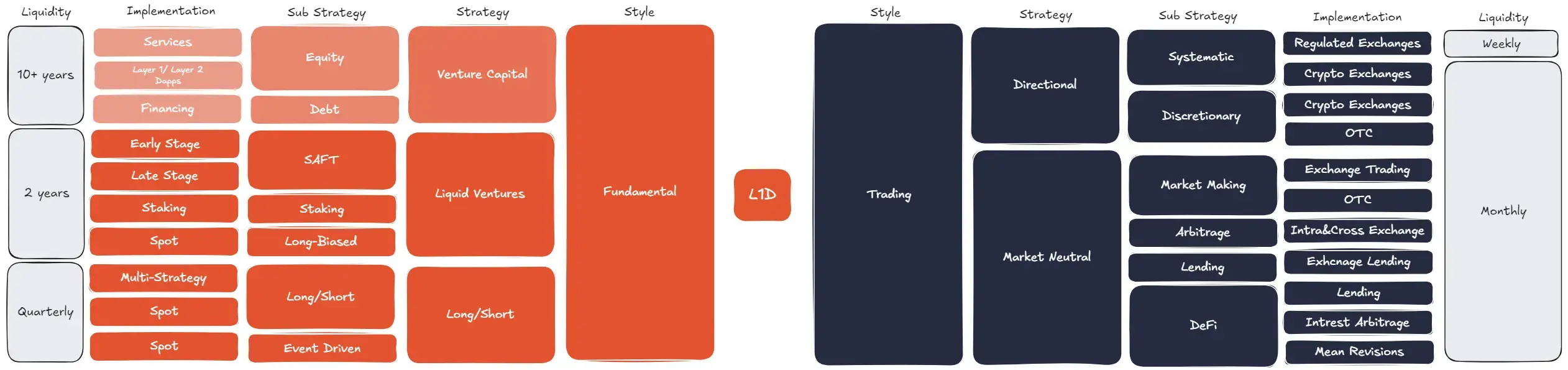

The investment strategy of a crypto hedge fund effectively defines the operational characteristics and requirements of the fund, as well as the corresponding workflows needed to prepare for launch. The chart below illustrates the strategy layout categorized by us at L1D. As each strategy further defines itself through sub-strategies, implementation, and liquidity, the operational characteristics of the fund are also defined — as the saying goes, form follows function. This ultimately manifests in the specific fund's structure, legal documents, counterparty and venue selection, policies and procedures, accounting choices, and the responsibilities of the fund manager.

L1D Strategy Framework

Fund Structure, Terms, and Investors

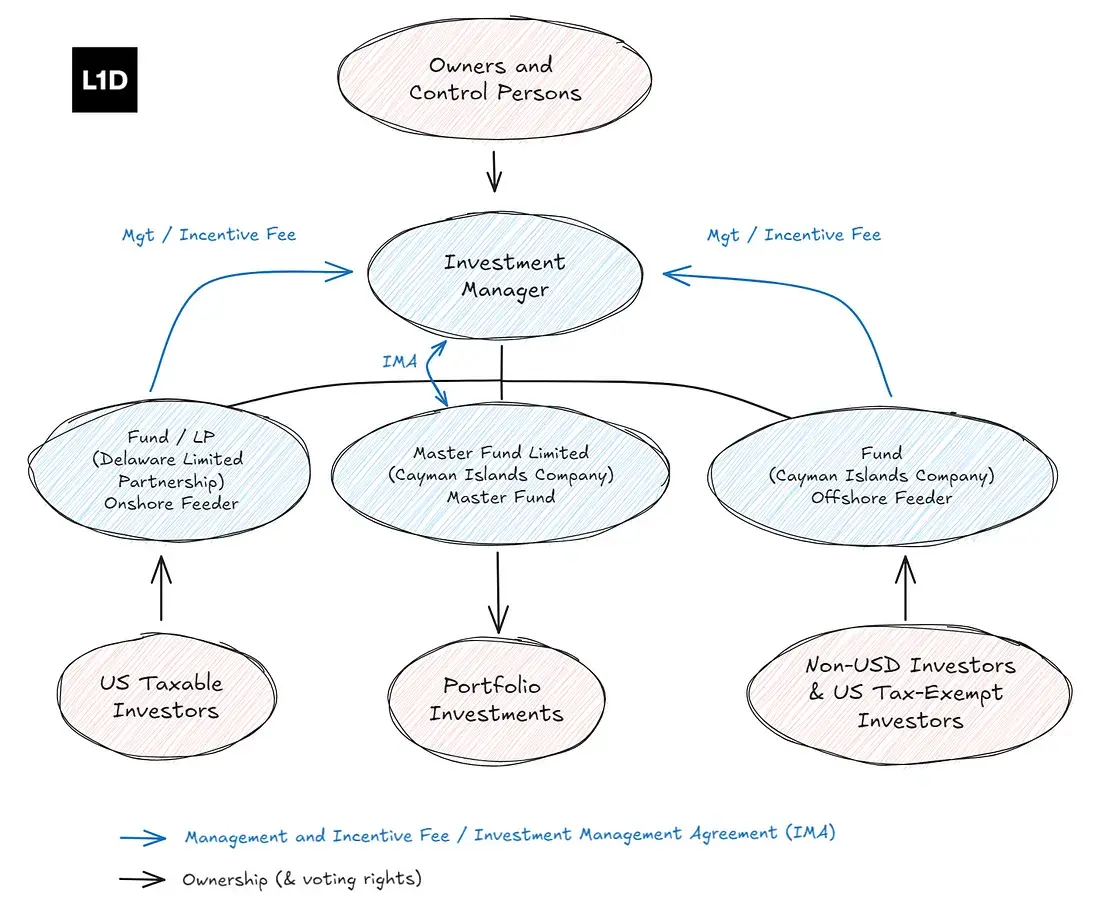

The structure of the fund is typically determined by the assets being traded, the tax preferences of the investment manager, and the residency of potential investors. Most institutional funds choose a domicile that allows them to face offshore exchanges and counterparties while attracting both U.S. and non-U.S. investors. The following section details the fund's offering documents and provides further details on several key items. This includes several case studies highlighting how certain choices in structure and offering document language can lead to potential negative outcomes for investors and outright failures.

The chart below illustrates a typical Cayman Islands-based master-feeder fund (also known as a master-feeder or parent-subsidiary) structure.

Typical Fund Structure

Investor Types and Considerations

At a high level, when establishing a fund, investment managers should consider the following characteristics of potential investors to address legal, tax, regulatory impacts, and business considerations.

Residency — U.S. vs Non-U.S.

Investor Type — Institutional, Qualified Investors vs Non-Qualified Investors, Qualified Purchasers

Number of Investors and Minimum Subscription Amount

ERISA (U.S. Employee Retirement Income Security Act)

Transparency and Reporting Requirements

Strategy Capacity

Offering Documents

The following items are key factors to consider when structuring the fund, typically included in the fund's offering documents — private placement memorandum and/or limited partnership agreement.

Domicile

Institutional-level funds typically choose the Cayman Islands as their primary domicile, with the British Virgin Islands being a less common choice. These domiciles allow fund entities to face counterparties — trading with offshore counterparties.

Choosing the Cayman Islands as the preferred jurisdiction is a result of traditional financial hedge funds being established there, and it has formed a service provider ecosystem around it, including legal, compliance, fund management, and auditing, establishing a strong track record in alternative asset management. This advantage has also carried over into the crypto space, as many of the same well-known service providers have now established businesses in this field. Compared to other jurisdictions, the Cayman Islands is still viewed as the "best choice," and the enhanced regulation from its regulatory body, the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA), supports this.

The maturity of these jurisdictions is reflected in higher regulatory clarity and legal precedents in fund management, as well as highly developed anti-money laundering (AML) and know your customer (KYC) requirements, which are crucial for a well-functioning market. These jurisdictions are often associated with higher costs.

The Cayman Islands has the highest costs and legal setup time, leading many managers to consider the British Virgin Islands. The British Virgin Islands is continuously establishing itself as an accepted jurisdiction, and as more high-quality and reputable service providers offer services there, its comparability to the Cayman Islands is increasing. The premium paid for choosing a well-known jurisdiction is often justified over the fund's lifecycle.

Fund Entities — Master Fund and Feeder Fund

According to the structure diagram above, there are typically master fund and feeder fund entities, with the master fund holding investments, participating in and executing all portfolio investment activities, and distributing financial returns to the underlying feeder fund.

The master fund is typically a Cayman limited company (LTD).

The feeder fund for offshore investors is usually a Cayman limited company, while the feeder fund for U.S. onshore investors is typically a Delaware limited partnership (LP). U.S. onshore feeder funds can also be Delaware limited liability companies (LLC), but this is less common.

Fund Entity Forms — Limited Company vs Limited Partnership

Offshore funds and master-feeder fund structures can cater to diverse sources of capital, including U.S. tax-exempt investors and non-U.S. investors.

The choice between a limited company (LTD) or a limited partnership (LP) structure is typically driven by the tax considerations of the fund manager and how they wish to receive performance fee compensation, which usually applies at the master fund level.

Cayman Limited Company ("LTD"): An independent legal entity separate from its owners (shareholders). Shareholders' liability is typically limited to the amount invested in the company.

LTDs usually have a simpler management structure. They are managed by directors appointed by shareholders, with day-to-day operations overseen by senior management — typically the investment manager.

Shares of an LTD can be transferred, providing flexibility for ownership changes.

LTDs have the flexibility to issue different classes of shares with varying rights and preferences. This can be advantageous for constructing investment vehicles or accommodating different types of investors.

LTDs typically choose to be treated as corporations for U.S. tax purposes, thus paying taxes at the LTD level without passing it through to investors.

Cayman Limited Partnership ("LP"): In a limited partnership, there are two types of partners — general partners and limited partners. General partners are responsible for managing the partnership and bear personal liability for its debts. In contrast, limited partners have limited liability and do not participate in day-to-day management.

LPs involve general partners ("GP") who are responsible for managing the partnership. GPs bear unlimited personal liability, while LPs enjoy personal liability protection.

Cayman does not tax foreign limited partnerships.

LPs have different structures, and limited partners typically contribute capital but do not have the same flexibility in share classes.

Delaware Limited Partnership ("LP"): The choice between implementing a Delaware LP or a Cayman LP can be nuanced, often related to investors' tax and governance preferences. Delaware LPs are the most common for onshore funds.

Delaware's LP laws define governance and investor rights.

For tax purposes, it is a "pass-through entity," meaning LP/investors pay taxes themselves.

The governance documents of the fund provide flexibility in defining the relationships between the parties.

Delaware LPs are typically cheaper and faster to set up.

Investment Manager/Advisor/Sub-Advisor/General Partner (GP)

An entity with portfolio management decision-making authority that is compensated through management fees and incentive fees.

Entities with decision-making authority and fee collection typically depend on the ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs), their respective nationalities, and tax preferences.

Typically established as a limited liability company (LLC) to leverage limited liability protection, as the GP (general partner) has unlimited liability.

Asset Holding Structure

Investments are usually held at the master fund level, but other entities may be established for certain assets/holdings, driven by tax, legal, and regulatory considerations.

In certain special cases, investments may be held directly by the feeder fund for the same reasons mentioned above, and the ability to do so must be explicitly stated in the fund's legal documents.

Share Classes

The fund may offer different classes of shares with varying liquidity, fee structures, and the ability to retain certain types of investors; typically, founder share classes are offered to early investors who make significant capital contributions. Such share classes may provide early investors with certain preferential terms to support the fund's development in its early stages.

Special classes may be created for special situations, such as for assets with limited liquidity, commonly referred to as side pockets (see below).

Different share classes may have different rights from one another, but the assets within each share class are not legally distinguished or isolated from the assets of other share classes — such examples will be covered in the case studies below.

Fees

The market standard for management fees is to align with the liquidity of the fund — for example, if the fund offers monthly liquidity, then management fees should be charged on a monthly basis (post-facto). This approach is also the most operationally efficient. As described below, a lock-up period is typically imposed during which management fees are charged.

Performance fees are usually accrued within a given year and are only settled and paid based on the corresponding high-water mark (HWM) on an annual basis. If an investor redeems at a net asset value above the HWM during the performance fee period, the performance fee is also typically settled and charged.

Some funds may prefer to settle and charge performance fees quarterly — this is not considered best practice, is not the market standard, is not favored by investors, and is less common.

For assets held in side pockets, performance fees will not be charged until they are realized, and only when they are transferred back to the liquid portfolio, either as liquid holdings or in cash form after realization.

Liquidity

Redemption terms and corresponding provisions — should align with the liquidity of the underlying holdings.

Lock-up period — determined at the discretion of the investment manager, typically driven by strategy and underlying liquidity. Lock-up periods may vary, with 12 months being quite common, but they can also be longer. Lock-up periods may apply to the initial subscription of each investor or to each subscription — both initial and subsequent. Different share classes may have different lock-up periods, meaning that the founder class may have a different lock-up period than other share classes.

Side pockets — see below.

Gates — the fund may impose restrictions at the fund or investor level — restrictions mean that if the assets of the fund or investor requesting redemption exceed a certain percentage (e.g., 20%) during any redemption window, the fund can limit the total amount of redemptions accepted — this is done to protect the remaining investors from the impact of large redemptions on pricing or portfolio construction.

Restrictions are typically associated with less liquid assets, as the impact of large redemptions may affect the actual price of assets when selling/liquidating assets to raise cash for redemptions, a characteristic that indeed protects investors.

The choice of imposing restrictions at the investor level or fund level is driven by the concentration of assets under management within the liquidity structure and investor base. However, it is more common to implement restrictions only at the fund level, which is more favorable to investors and operationally more efficient.

It is also important that the restriction terms clearly state that investors who submit redemption requests before restrictions are imposed should not have priority over those who submit redemption requests after restrictions are imposed — this ensures that later redemptions are treated equally with earlier redemptions and eliminates any motivation or possibility for large investors to exploit the system and gain unintended advantages in liquidity.

Fees

The fund may allocate certain operational expenses to the fund, which are effectively paid by the investors.

Best practice is to allocate expenses directly related to fund management and operations to the fund, and not create conflicts between the fund and the investment manager. Remember that managers receive management fees for their services, so operational and other expenses related to the management company and entity should not be charged to the fund. Direct fund expenses are typically related to servicing investors and maintaining the fund structure — including administration, auditing, legal, regulatory, etc. Management company expenses include office space, personnel, software, research, technology, and costs necessary to operate the investment management business.

Managers should focus on the total expense ratio (TER). Newly launched crypto funds typically have relatively low assets under management (AuM) for a period. Institutional investors' allocations to cryptocurrencies may carry new risks associated with exposure to this asset class, which should not be exacerbated by a high total expense ratio (TER).

To keep the TER at a reasonable level, enhance accountability, and align the manager with investors, it is recommended — and also a sign of confidence — that managers commit to bearing certain start-up and ongoing operational expenses. This indicates a long-term commitment to the space and an expectation that the growth of AuM from this commitment will compensate the manager for this investment and discipline.

Good fee management can further align managers and investors by alleviating potential conflicts of interest. There may be gray areas between what directly benefits the fund and what benefits the manager more than the fund — for example, industry presence at meetings and events, as well as related fee policies. The costs incurred to maintain such presence are not direct fund expenses and are more likely to be included in management fees, or even borne by the manager themselves.

The crypto space is already rife with conflicts, and adopting a truly fiduciary approach to fee policies is crucial for enabling institutional investors to invest in cryptocurrencies.

Accounting

To accurately track the high-water mark used for performance fee calculations, two applicable accounting methods can be employed — series accounting or equalization.

Series or multi-series accounting ("series") is a procedure used by fund managers where the fund issues multiple series of shares for its fund — each series starts with the same net asset value (NAV), typically $100 or $1,000 per share. A fund that trades monthly will issue a new series of shares for all subscriptions received each month. Thus, the fund will include shares such as "Fund I — January 2012 Series," "Fund I — February 2012 Series," or sometimes referred to as Series A, B, C, etc. This makes tracking the high-water mark and calculating performance fees very straightforward. Each series has its own NAV, depending on the position of the series relative to the investor's high-water mark at year-end; those series at the high-water mark will "aggregate" at year-end into the main class and series, while those below the high-water mark will also aggregate as they are "below water." This process requires a significant amount of work at year-end, but once completed, it becomes easier to understand and manage going forward.

In equalization ("EQ") accounting, all shares of the fund have the same NAV. When new shares are issued/subscribed, they are subscribed at the total NAV, depending on whether the NAV is above or below the high-water mark, and investors will receive an equalization credit or debit. Investors who subscribe below the high-water mark will receive a statement showing their share count and equalization debit (for future performance incentive fees from their entry NAV to the high-water mark); if they subscribe above the high-water mark, investors will receive an equalization credit to compensate for any potentially overcharged incentive fees between their purchase NAV and the high-water mark. Equalization accounting is considered quite complex, adding an additional burden to fund administrators, many of whom may not be equipped to handle it. This is also true for the operational and accounting staff of the fund manager.

Neither method is superior, as investors are treated equally in both cases, but series accounting is generally more favored because it is more straightforward and easier to understand (its downside is that it generates many series, which may not always aggregate into the main series, thus potentially leading to many different series over time, increasing the operational and reporting workload for administrators).

First in, first out (FIFO) — redemptions are typically processed on a "first in, first out" basis, meaning that when an investor redeems, the shares being redeemed belong to the series they subscribed to earliest. This is more favorable to the manager, as if these (earlier) shares are above their high-water mark, such redemptions will trigger the settlement of performance fees.

In certain cases, managers may choose to apply leverage to strategies through accounting mechanisms rather than separate fund tools — this is not recommended, and the reasons for not doing so will be detailed in the case studies below.

Side Pockets

In crypto investing, certain investments, typically early protocol investments, may lack liquidity. Such investments are usually held outside the regular portfolio and are separated into a side pocket category, which cannot be redeemed alongside liquid holdings during normal redemption intervals.

Side pockets gained widespread attention during the 2008 crisis/global financial crisis — side pockets were initially provisions that allowed funds running otherwise liquid strategies to invest in illiquid holdings, typically with restrictions in terms of AuM percentage and defined liquidity catalysts, such as IPOs. However, due to the impact of the global financial crisis, a larger portion of what was originally liquid portfolios became illiquid and was placed into side pockets, leading to significant redemptions for such funds, meaning all liquid assets needed to be liquidated. The side pocket mechanism ultimately protected investors from assets being sold at discounted prices, but investors in liquid funds ended up holding unexpectedly larger amounts of illiquid holdings. The original intent of side pocket provisions did not anticipate these compounded effects of the crisis, and thus the handling of side pockets and their impact on investors — including valuation and fee basis — was not adequately considered.

Side pockets themselves are a useful tool in the crypto space, but implementing side pockets requires careful consideration. Side pocket investments have the following characteristics:

They should only be created when there is a genuine need to protect investors.

Ideally, they should be limited to a specific percentage of the fund's AuM.

They cannot be redeemed during normal redemption intervals.

They must (should) be held in their own legal share class, not just separated through accounting mechanisms.

Management fees should be charged but performance fees should not be charged — performance fees will only be charged when the holdings become liquid and are moved back to the liquid portfolio.

Not all fund investors have access to side pockets — typically, only investors who were already fund investors at the time of the creation of the side pocket investment will be allocated to the side pocket exposure, and investors entering the fund after the creation of any specific side pocket investment will not have access to existing side pockets.

Key considerations when constructing side pockets:

Offering documents — should clearly state the allowance and intention to use side pockets; if the fund structure is master-feeder, both sets of offering documents should reflect the handling of side pockets.

Separate share classes — side pocket assets should be placed in their own class with corresponding terms — for example, management fees charged, no performance fees, no redemption rights.

Accounting structure within the fund structure — side pockets are typically created when making illiquid investments and/or when existing investments become illiquid; only investors who were invested in the fund at the time of the creation of the side pocket should have access to the side pocket, and such investors typically subscribe to that side pocket class. When assets in the side pocket become liquid, they are typically redeemed from their class and then placed into the liquid share class, with investors holding that exposure subsequently subscribing to the newly created liquid class — this ensures accurate tracking of investor exposure and high-water marks. If the fund structure is master-feeder, the side pocket at the feeder fund level should have a corresponding side pocket at the master fund level to ensure there is no potential liquidity mismatch between the feeder and master funds.

The following matters are not directly considered in the fund's offering documents, but policies must be established to ensure alignment of interests and clear communication with investors:

Migration from Side Pocket Class to Liquid Class — There should be a clear policy outlining when assets have sufficient liquidity to be transferred from the side pocket class to the liquid class. This policy and rules are typically based on some measure of exchange liquidity, trading volume, and the fund's ownership of existing liquidity.

Valuation — When a side pocket is created, it is usually valued at cost as the basis for charging management fees. Assets in the side pocket can be marked up in valuation, but must adhere to clear and practical valuation guidelines. One method may include applying a marketability discount (DLOM) based on recent large transactions of the asset (e.g., recent financing at a valuation above the fund's original cost).

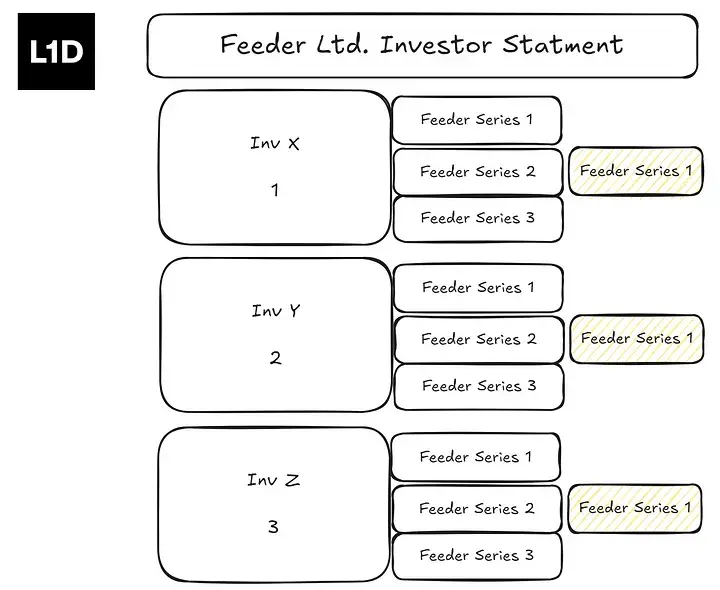

Reflection in Investor Statements — Investors should clearly understand their liquidity in the fund, so the side pocket class should be reported separately from the liquid class (each liquid class should also be reported separately) to ensure investors know their share count and net asset value per share, which can be redeemed according to standard liquidity terms.

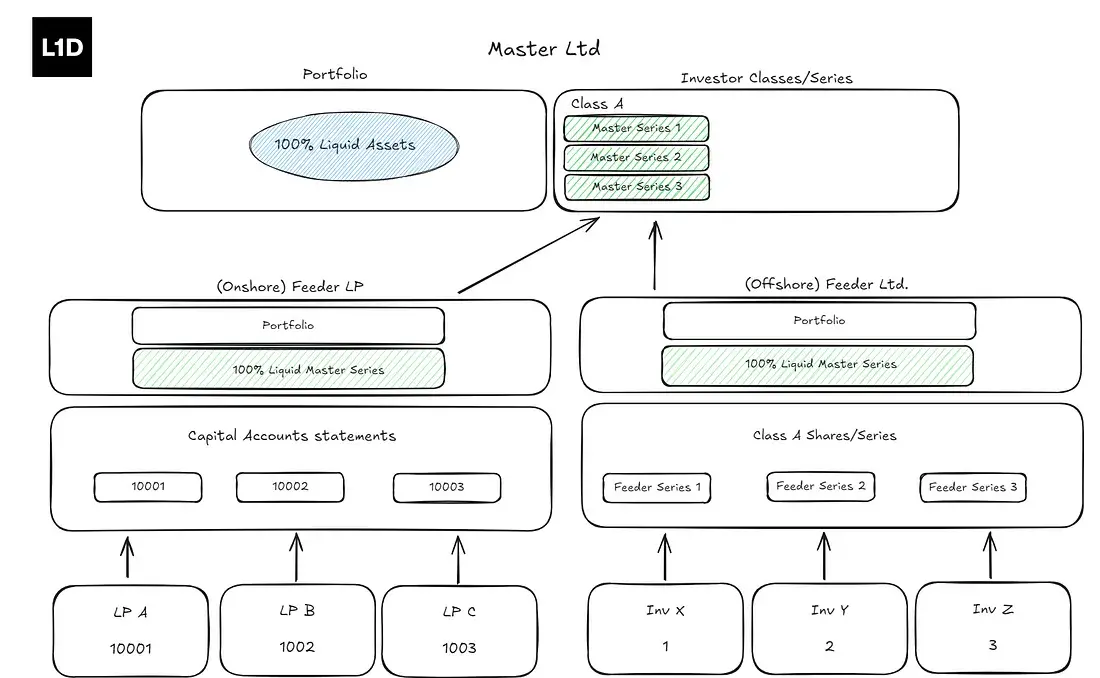

Example Side Pocket Structure

The following example structure diagram reflects a generic version of how investors are allocated side pocket exposure.

For illustrative purposes, an Offshore Feeder Ltd. is used here, as the limited company utilizes share class accounting, which is more suitable for illustrating certain key points related to this accounting concept and its application in side pockets. A similar mechanism applies to an Onshore Feeder Limited Partnership, but is not detailed in this example.

The Master Fund holds actual crypto investments in its portfolio. Each feeder fund invests in share classes of the master fund and is a shareholder of the master fund.

Investors in the feeder fund receive shares of the feeder fund — this is a fund that accepts subscriptions monthly, and when investors subscribe in a specific month, a series is created for that month to appropriately account for and track performance and calculate corresponding incentive fees. The performance of the master fund's portfolio is allocated to feeder fund investors based on the changes in the value of the master fund shares through the feeder fund, as well as the corresponding growth in the value of their feeder fund shares.

When the master fund holds only liquid assets, feeder fund investors indirectly own a proportional share of all the liquid assets of the master fund. In this case, 100% of the master fund shares are liquid, and thus the feeder fund shares are also liquid and eligible for redemption according to the terms of the fund. Their feeder fund shares' performance will be 100% based on the performance of the master fund shares, ultimately derived from the master fund's portfolio (specific performance is accounted for at the series level).

In the chart below (Figure 1), the master fund holds only liquid investments in January, and the entire performance will be allocated to feeder fund investors, with all feeder fund series benefiting from the performance of the master fund, and each identical series (i.e., subscribed in the same month) will have the same performance.

Master Fund supports liquid investments

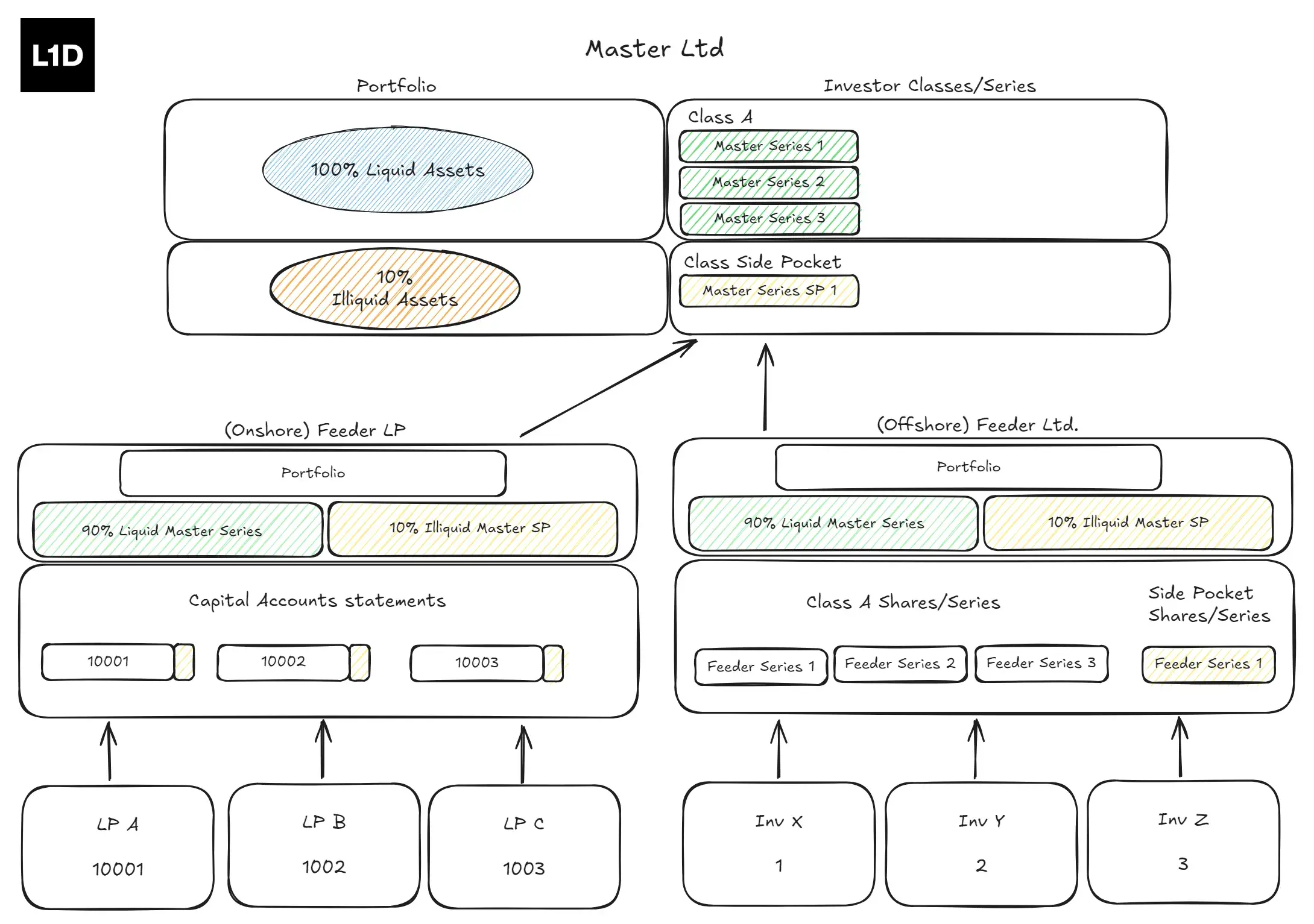

Figure 2 shows a master fund portfolio that determines that 10% of its investments are illiquid in February.

Master Fund holds liquid and illiquid assets and issues side pockets

When certain portions of the master fund portfolio lack liquidity, these assets cannot be sold to meet redemption requests from feeder fund investors. Assets may lack liquidity for two main reasons — either certain assets become illiquid due to some distress, or the master fund invests in illiquid assets due to special opportunities. In either case, only feeder fund investors who were invested when these illiquid assets entered the master fund portfolio should have exposure to these illiquid assets — from the perspective of fees and performance, as well as from the perspective of changes in their holdings' liquidity.

To address the issue of certain parts of the portfolio lacking liquidity, the master fund will create a side pocket in February to hold these illiquid assets, and only feeder fund investors who were invested before February will have exposure to the side pocket — they will gain or lose from the future performance of the side pocket. Crucially, after the creation of the side pocket (which will be accomplished by converting and transferring 10% of its liquid shares into side pocket shares), they will only have 90% of their shares eligible for redemption (since 10% of their initial liquid shares have been converted to side pocket shares). Investors who subscribe to the master fund in March will not have exposure to the side pocket created in February.

The master fund will create a special share class to hold the side pocket assets — namely, SP class shares. When this occurs, the feeder fund's portfolio will hold two types of assets (liquid master fund shares and non-redeemable master fund SP shares), and a corresponding side pocket share class must be created to hold the illiquid exposure, such as the master fund SP shares. This is to ensure proper accounting and liquidity management to match the liquidity exposure of the master fund, as the investment date of investors is now crucial for determining their exposure, performance, and fees. When feeder fund investors redeem (only from the liquid class, i.e., Class A shares), the feeder fund will redeem part of the liquid shares from the master fund to raise funds for the redeeming investors. The feeder fund's SP shares (like the master fund's SP shares) are non-redeemable.

Separate accounting for each side pocket and corresponding class is necessary to ensure that value is fairly allocated.

In this structure, investors in the offshore feeder fund gain corresponding exposure at the master fund level from both accounting and legal perspectives (a similar mechanism exists among investors in the onshore feeder fund). This ensures that only actual liquid assets can be sold at the master fund level to raise cash for redemptions at the feeder fund level.

Investors in the offshore feeder fund will receive investor statements reflecting their liquid class and side pocket class, so they know their total capital and which capital is available for redemption.

Feeder Ltd. Investor Statement

This accounting treatment and appropriate structural design are not well understood by many managers and service providers. Close coordination among investment managers, legal advisors, fund administrators, and auditors is crucial to ensure the enforceability of the structure and rights, as well as compatibility with the terms of the offering documents.

Governance

Board of Directors — Good governance practices require that there be at least one independent member on the fund's board of directors, and independent directors should typically constitute a majority, meaning that the number of independent directors exceeds that of affiliated directors (e.g., CEO and/or CIO). Typically, the directors of offshore funds are provided by companies specializing in such corporate services in the fund's jurisdiction of registration. If possible, it is preferable to have an independent director with practical operational experience and expertise who can add value when dealing with complex operational issues — such individuals can also provide value as advisors rather than formal directors.

For newly established crypto funds, independent boards are becoming increasingly common, but the fees associated with directors are borne directly by the fund.

Side Agreements — The fund may enter into side agreements with certain investors to provide them with certain rights not directly stipulated in the fund's offering documents. Side agreements should typically be reserved for large, strategic, and/or early investors in the fund. Side agreements may include terms related to information rights, fee terms, and governance matters.

Regulatory Status

Funds are typically regulated by local corporate or mutual fund laws in their jurisdiction. In the United States, even if a fund is exempt from SEC registration and the investment manager is not registered as a registered investment advisor (RIA) under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, the SEC and other regulatory bodies (such as the CFTC) can still oversee and enforce regulations.

Emerging managers often choose to be viewed as ERA (Exempt Reporting Advisors), which have much lower reporting requirements. In the U.S., funds will be classified under the private fund category of the Investment Company Act of 1940. Two common categories are 3(c)(1), which allows fewer than 100 investors, or 3(c)(7), which only allows qualified purchasers (individuals with $5 million in investable assets, entities with $25 million in investable assets). Many new funds choose to become 3(c)(1) due to lower reporting requirements. However, managers must recognize that due to the limited number of allowed investors, they may not want to accept small subscriptions to manage this investor "budget" within the acceptable number of investors for the fund.

Under the Securities Act of 1933, private funds can raise capital through Rule 506(b), which allows fundraising but prohibits general solicitation; or through Rule 506(c), which allows general solicitation but comes with higher reporting requirements.

Establishing an entity typically requires hiring legal counsel in each jurisdiction for appropriate filings, as well as ongoing maintenance and compliance.

Physical Subscriptions and Redemptions

Funds may choose to accept subscriptions from investors in cryptocurrency (physical).

In some cases, funds may be allowed to pay redemptions in kind — this is usually not ideal and may create regulatory and tax issues, as investors may lack the technical capability to custody the assets, or may not be permitted to hold crypto assets directly from a regulatory perspective.

Physical subscriptions may bring valuation, tax, and compliance issues. Typically, to avoid valuation issues, physical subscriptions only accept BTC or ETH. From a tax perspective, in the U.S., physical subscriptions may trigger tax events for investors, which need to be considered. In terms of compliance, physical subscriptions will be wallet-to-wallet transactions, so fund administrators and fund agents accepting subscriptions should have the capability to conduct appropriate KYC on the sending wallet address, and investors should be aware of this. If the fund does accept physical subscriptions from investors, then when that investor redeems, best practice from an anti-money laundering perspective is to pay the redemption amount in kind equal to the amount of the physical subscription, with any profits paid in cash.

Key Person Risk

Key person clauses allow investors to redeem outside of the normal redemption window if a key person (such as the CIO) loses capacity or is no longer involved with the fund — including such clauses is considered best practice.

Case Studies

The following case studies highlight choices in fund structures and how they are reflected in offering documents, which can lead to adverse or potentially disastrous outcomes for investors. These choices are understood to be made by their respective managers with the best intentions, often to achieve operational and cost efficiencies.

Side Pockets

A fund offers investors side pocket exposure but does not create a legally independent side pocket, only recording the side pocket exposure in accounting.

The intent of the manager and the fund is clear, and the accounting treatment is correct.

However, because a legal side pocket was not created, fund investors theoretically and legally can redeem their entire balance — including both liquid and illiquid side pocket holdings — and are legally entitled to their full balance according to the terms of the fund documents.

The investor statements received by investors do not reflect the side pocket class (because none was created), so they may believe that the entire reported net asset value (NAV) is available for redemption.

If a large investor in the fund indeed redeems in such a manner within their legal rights, it would force the manager to liquidate illiquid assets under extremely unfavorable conditions, harming the interests of remaining investors, and/or sell the fund's most liquid assets, leaving the least liquid assets to the remaining investors, thereby putting the entire fund at risk of collapse.

Ultimately, this issue was rectified by providing a clear definition in the updated fund legal documents, creating formal and legal side pockets, and appropriate investor reporting.

It is worth noting that this issue was discovered by L1D.

The fund's manager, auditor, fund administrator, and legal advisors all believed that the initially designed and implemented structure was reasonable and appropriate. A further lesson is that even experienced service providers are not always correct, and managers must possess such expertise themselves.

Structural Design

The strategy that L1D intended to invest in was actually a share class of a larger fund (the "umbrella fund") that offers various strategies through different share classes. Each share class has its corresponding fee terms and redemption rights.

The umbrella fund is a standard master-feeder fund structure.

On the surface, this seems like a way to expand various strategies through a single fund structure to save costs and execution fees. However, a provision in the "risk" section states:

Cross-Class Liability. For accounting purposes, shares of each class and series will represent a separate account and will maintain separate accounting records. However, this arrangement is only binding among shareholders and is not binding on external creditors trading with the fund as a whole. Therefore, all assets of the fund may be used to satisfy all liabilities of the fund, regardless of which assets or liabilities belong to any individual portfolio. In practice, cross-class liability typically only arises when a class goes bankrupt or exhausts its assets and cannot meet all its liabilities.

What does this mean? It means that if the umbrella fund is liquidated, the assets of each share class will be considered assets available for the creditors of the umbrella fund, potentially wiping out the assets of each share class.

What happened? The umbrella fund ultimately collapsed and was liquidated due to poor risk management, with the assets of each share class, including the specific share class that L1D considered as an investment opportunity, being included in the bankruptcy estate. The fund and the assets of that share class subsequently became the subject of extensive litigation, leaving investors essentially powerless and without hope of recovery.

The failure of risk management at the investment level led to the collapse, while operational/structural weaknesses resulted in further capital losses for investors who had not engaged with the actual failed strategy. A relatively blandly stated and poorly considered structural decision in the PPM led to significant losses for investors in a stressed scenario. The risk was effectively buried in the PPM as a key risk factor, although not intentionally hidden.

Based on this structure, L1D abandoned the investment during preliminary due diligence.

Accounting Leverage

The following case study provides a risk perspective when attempting to apply different strategies at the share class level rather than through separate funds that own their respective assets and liabilities. Its narrative is very similar to the previous example — a failure in risk management during the investment process, amplified by structural weaknesses.

The fund offered leveraged and unleveraged versions of its strategy through share classes within a single fund.

The fund is a single pool of capital, with all collateral in a single legal pool with the fund's counterparties — all profits and losses are attributed to the entire fund, and the manager allocates profits and losses on an accounting basis according to the leverage of the share classes.

The fund's strategy and corresponding risk management processes changed without notifying investors, coinciding with a significant market event that effectively wiped out the fund's collateral with its counterparties, leading to massive liquidations.

According to the leverage ratios defined at the share class level, investors in the unleveraged share class would have expected significant losses but not a total loss. Similarly, the cross-class liability risk conveyed in the PPM communicated this risk, but investors in the unleveraged share class did not fully understand it.

The fund's failure was the result of a confluence of events — an unannounced strategy change and poor risk management coinciding with a market tail event, combined with structural choices, meant that investors intending to gain unleveraged exposure were still affected by the application of leverage.

Delayed Net Asset Value (NAV) Reporting

See the service provider section, fund administrator.

Operational Stack

The operational stack is defined here as the complete system of all functions and roles that the manager must undertake to execute its investment strategy. These functions include trading, financial management, counterparty management, custody, middle office, legal and compliance, investor relations, reporting, and service providers.

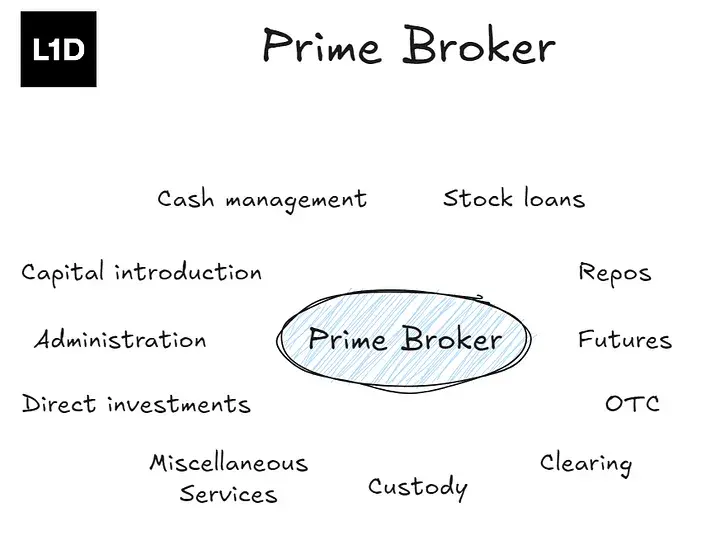

In traditional finance (TradFi) trading activities, there are several specialized participants that ensure secure settlement and ownership — the chart below reflects the parties involved in U.S. stock trading.

In crypto trading and investment, exchanges and custody form the core infrastructure, as their combined functions create a parallel architecture to traditional financial settlement and prime brokerage models. Since these entities are at the core of all transactions, all processes and workflows are developed around interactions with them. The chart below illustrates the role of prime brokers and the services they provide.

In traditional finance, a key function of prime brokers is to provide margin, collateral management, and net settlement. This allows funds to achieve capital efficiency across positions. To provide this service, prime brokers typically can re-hypothecate client assets held in custody (for example, lending securities to other clients of the prime broker).

While prime brokers play a critical role in managing counterparty risk, the prime broker itself is the main counterparty to the fund and also constitutes a risk. The re-hypothecation mechanism means that client assets are lent out, and if the prime broker fails for any reason, fund clients become creditors, as re-hypothecation means that client assets no longer belong to the client's property.

In the crypto space, there is no institution that directly corresponds to traditional financial prime brokers. Over-the-counter (OTC) desks and custody providers are attempting to fill this role or some aspects of it in different ways. FalconX and Hidden Road are two examples. However, given the discrete nature of cryptocurrencies — particularly as underlying assets are located on different blockchains that may not necessarily be interoperable — the reporting systems of exchanges are also more limited and operate across various jurisdictions, making prime brokerage in the crypto space still a developing area. Most importantly, the motivation for an entity to first become a prime broker is the ability to re-hypothecate client assets, which is a clear aspect of its business model. The failures of prime brokers during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) demonstrated the counterparty risk that prime brokers themselves pose to their hedge fund clients. Given the weaker capital strength of brokers and exchanges, lower levels of regulatory or investor oversight of risk management, and the lack of bailouts during crises, this counterparty risk in cryptocurrencies is amplified. The inherent volatility of cryptocurrencies and the risk management challenges it brings further exacerbate this. These factors make it very difficult to apply the traditional financial prime brokerage model to cryptocurrencies in a "safe" manner from a counterparty risk perspective.

The prime brokerage model is useful in defining the operational stack of crypto investment managers, as managers internally assume most of the functions of a prime broker and/or assemble various functions across multiple service providers and counterparties. These roles and skills are often both internalized and outsourced, but given the nature of available service providers in the space, most, if not the majority, of expertise should be expected to be internal, and the manager's own domain knowledge is crucial.

Operational Stack of Crypto Hedge Funds

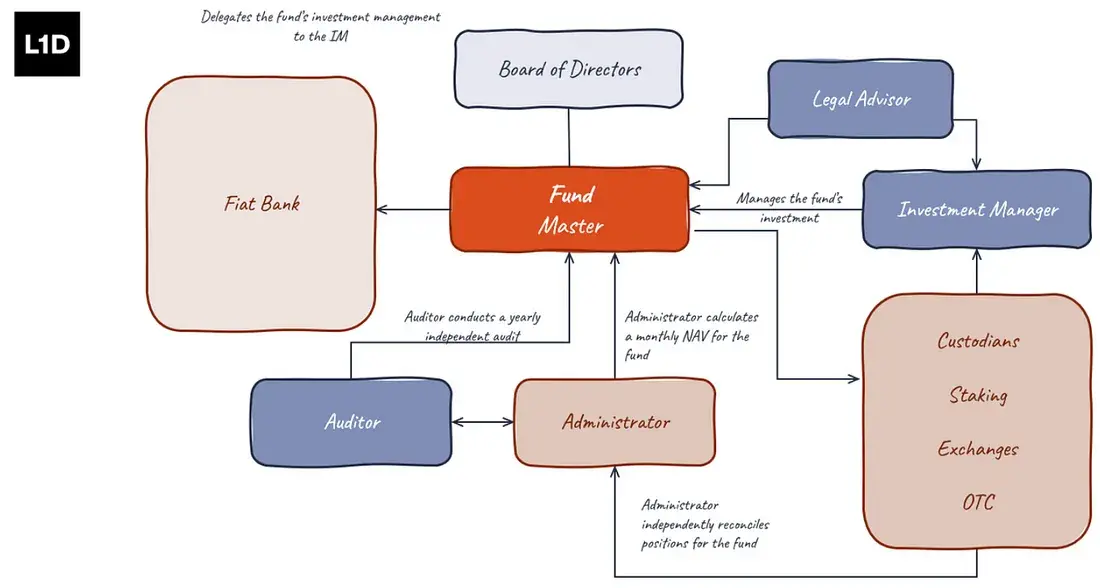

The following are the main operational functions in a crypto hedge fund (Crypto HF). Maintaining a degree of separation between operations and investment/trading is still important, which often applies to signature policies involving asset movement.

Middle Office/Back Office: Fund accounting, trade and portfolio reconciliation, net asset value (NAV) generation — typically overseen and managed by the fund administrator.

Financial Management: Managing cash and equivalents, collateral on exchanges, stablecoin inventory, banking relationships.

Counterparty Management: Conducting due diligence on counterparties, including exchanges and OTC desks, opening accounts with counterparties and negotiating commercial terms, establishing asset transfer and settlement procedures between fund custody assets and counterparties, setting exposure limits for each counterparty.

Custody and Staking: Internal non-custodial wallet infrastructure, third-party custodians — including establishing whitelists and multi-signature (Multisig) procedures, maintaining wallets, hardware, and related policies and security protocols, conducting due diligence on third-party custodians.

IT and Data Management: Data systems, portfolio accounting, backup and recovery, cybersecurity.

Reporting: Internal reporting, investor reporting, audits.

Valuation: Developing and applying valuation policies.

Legal and Compliance: Managing external legal counsel, internal policies and procedures, handling regulatory filings and other matters including AEOI, FATCA, AML/KYC, etc.

Service Provider Management: Conducting due diligence on service providers, reviewing and negotiating service agreements, managing service providers, with a focus on the fund's administrator.

Operational Roles

Given the operational functions and responsibilities outlined above, when considering the appropriate skill set for operational personnel (typically the Director of Operations and/or Chief Operating Officer), the necessary skill set should include experience in these areas and may also depend on the fund's strategy and underlying assets. The required experience is typically divided into two categories:

Accounting and Auditing — Applicable to all funds, but particularly critical for funds with high turnover, numerous projects, and complex share structures (such as side pockets).

Legal and Structural — Applicable to funds that structure trading products and include tax and regulatory component strategies, often of some form of arbitrage.

In both cases, if there are gaps in an individual's expertise, such as an accountant lacking a legal background, these gaps are typically filled by external individuals (such as legal advisors). However, it is important to note that fund administrators in this space — as will be discussed in more detail below — often require significant oversight and management in the 3-6 months before and after launch. Individuals with experience in fund operations, fund management, or dealing with fund administrators, or accounting professionals, are typically very well suited to manage this process.

Best practice is for investment managers to maintain a set of shadow records for the fund, effectively executing a "shadow" system that corresponds to the records maintained by the fund administrator. This allows for three-way reconciliation between the investment manager, fund administrator, and financial counterparties. Three-way reconciliations are conducted at month-end to ensure all records match consistently.

Overview of entities involved in fund operations

Asset Lifecycle

The flow of assets from fund subscription, trading to redemption illustrates the functions of the operational stack. The following general lifecycle indicates key operational nodes:

Investor subscriptions are transferred to the fund's bank account

The subscription funds from investors are transferred to the fund's investor bank account, and after passing KYC/AML checks, the funds are moved to the fund's trading or operating account.

Fiat currency is transferred to fiat on-ramps (exchanges or OTC) and converted into (usually) stablecoins; typically, the fund administrator must act as a second signatory for the withdrawal of fiat currency from the bank account.

Stablecoin balances may be held on exchanges and/or with third-party custodians.

Investment Committee/Chief Investment Officer (CIO) Decision on Trades/Investments

Pre-approval for trades is required for compliance (e.g., personal trading policies) and/or risk management purposes.

Traders obtain liquidity through counterparties — exchanges or OTC — specifying order types such as market orders, limit orders, stop-loss orders, and possibly including execution algorithms like TWAP (Time Weighted Average Price) and VWAP (Volume Weighted Average Price).

Interactions with counterparties occur via API, portals, or chat tools (e.g., Telegram).

If trading listed assets on an exchange, stablecoin balances are used, and post-settlement assets are transferred to third-party custodians.

In OTC trades, some transactions may require pre-funding, or the OTC desk may provide a certain credit line — orders are executed, settled, and then assets are transferred to third-party custodians.

For perpetual contract trading — collateral balances must be maintained on the exchange, with periodic funding fees paid.

Clearing and settlement — verifying trade details during the settlement period; once the trade is settled, assets are transferred to storage/custody institutions.

The investment team assesses the impact on exposure and risk parameters.

The operations team reconciles all positions daily — assets, account balances (counterparty, custody, bank), prices, quantities, price references, calculating the profit and loss of the portfolio; internal reports are published.

At month-end, trading documents and reconciliation materials are provided to the fund administrator

The fund administrator independently verifies assets and prices with all counterparties, custodians, and banks — usually manually, via API, obtaining support from OTC desks (e.g., Telegram chat records), and/or using third-party tools (e.g., Lukka), applying fees and expense accruals.

The investment manager collaborates with the fund administrator to resolve discrepancies in reconciliation and calculate the final net asset value (NAV).

The fund administrator applies internal quality assurance (QA) processes to calculate the fund's net value and investor net value.

The fund administrator provides the final net asset value information to the investment manager for review and signature, releasing investor statements.

Investors submit redemption requests

Invested assets are transferred from custodians to exchanges/OTC, converted to fiat currency, and sent to the fund's investor bank account.

After the net asset value is approved

The fund administrator authorizes the payment of redemption funds to the redeeming investors.

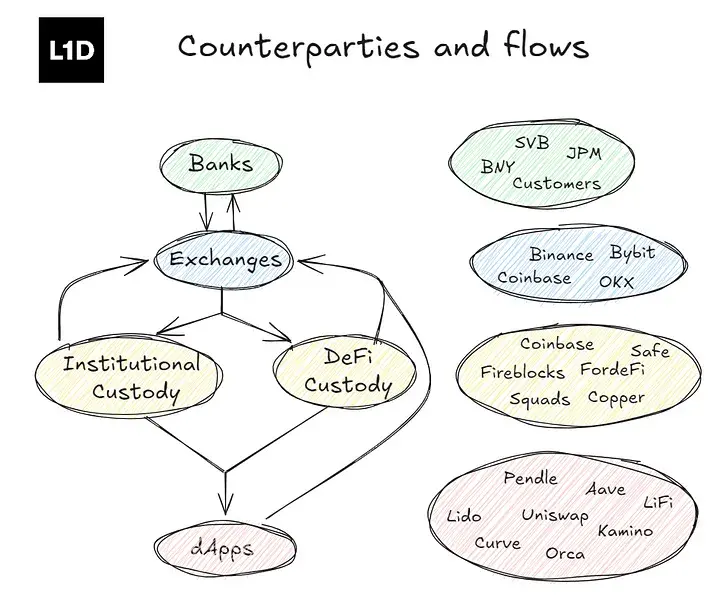

Summary of Counterparty Cash Flows

This chart reflects the cash flows described in the asset lifecycle.

Trading Venue and Counterparty Risk Management

Since the collapse of FTX, the fund has reassessed its approach to managing counterparty risk, particularly regarding whether to keep assets on any exchange and how to manage exposure to any entity holding fund assets at any time, including OTC desks, market makers, and custodians. Exchange custody is a form of custody (discussed in more detail in the "Custody" section) where the exchange holds client assets, which are mixed with the exchange's assets and lack bankruptcy isolation. The fund holds assets on exchanges because it is easier, more cost-effective, and more capital efficient.

It is also worth noting that agreements with OTC desks stipulate payment delivery (DVP), meaning clients pay before asset delivery. Additionally, these agreements typically state that such assets are mixed with other clients' assets rather than isolated or having bankruptcy isolation. Therefore, there remains a risk of OTC counterparty default before asset delivery. During the FTX collapse, certain OTC desks had unsettled client trades with FTX itself. These OTC desks became creditors of the FTX estate, and although they had no obligation, they chose to fully compensate clients using their own balance sheets. Formally underwriting exchanges and OTC counterparties has always been challenging, as financial statements may not be available and may be of limited use, although transparency is improving.

Counterparty Risk Management Approach

To appropriately manage counterparty risk, investment managers should develop policies compatible with their investment strategies. This may/should include defining:

- Maximum exposure allowed to any counterparty.

- Maximum exposure allowed to any type of counterparty — exchanges, OTC, custody.

- Maximum exposure allowed to any sub-category — qualified custodians vs. others.

- The longest time limit for trade settlement — usually measured in hours.

- The proportion of unsettled fund assets at any given time.

Other measures can be taken to monitor the health of counterparties, including regularly "pinging" counterparties with small trades to test response times. If response times exceed normal ranges, managers may shift exposure away from that counterparty. Fund managers are known to continuously monitor market activity, news, and the wallets of key participants to identify unusual activity, proactively respond to any potential defaults, and shift assets.

Considerations for DeFi

Decentralized exchanges (DEX) and automated market makers (AMM) can supplement the fund's counterparty range and serve as alternatives under certain conditions. When certain centralized participants face difficulties, their DeFi counterparts tend to perform relatively well.

When interacting with DeFi protocols, the fund converts counterparty risk into smart contract risk. Generally, the best way to underwrite smart contract risk is to determine exposure size in the same manner as defining counterparty exposure limits (as described above).

Additionally, when interacting with DeFi protocols, there are considerations regarding access and custody, which are discussed in more detail in Section 6 — Custody.

Tri-Party Structure

To manage counterparty risk associated with exchanges, several service providers have developed innovative approaches that implement a tri-party structure. The solutions detailed below have garnered significant attention.

As the name suggests, this arrangement involves (at least) three parties — two parties trading with each other and a third party — an entity managing the collateral involved in the trade, typically a custodian. The third party will monitor and manage the collateral assets involved in the trade.

A key feature of this structure is that the party managing the collateral maintains the assets in a legally isolated manner (usually in a trust), protecting both parties from the effects of the entity managing the collateral and the guarantee structure.

In this structure, the entity managing the collateral ensures that both parties deliver and pay, and then settlement occurs.

As part of the process, excess collateral is released or returned based on margin requirements, reports are provided to both counterparties, and assets are continuously monitored to ensure they are sufficient to support financial transactions between the counterparties.

Copper ClearLoop

Copper Technologies has implemented off-exchange settlement or custody-internal settlement through its ClearLoop product. In this setup, both parties — fund clients and exchange counterparties — effectively provide collateral to Copper (such collateral is held in trust), with Copper acting as a neutral settlement agent on behalf of both parties. This protects the fund from the risk of exchange counterparty default, safeguarding principal (collateral), but there remains a profit and loss risk if the counterparty defaults before the (profitable) trade settles.

Copper has been an early innovator in this setup, leveraging its custody technology and existing exchange integrations.

All other major custodians, including Anchorage, Fireblocks, Bitgo, and Binance, are using legal structures and technology to develop their own tri-party agreements and/or may collaborate with Copper.

Hidden Road

Hidden Road Partners (HRP) has developed a form of prime brokerage that offers capital efficiency and counterparty risk protection. HRP raises capital from institutional investors and pays them capital returns, with funds sourced from providing trading financing to clients. HRP reduces its risk by setting risk limits and requiring partial collateral to be provided in advance. Clients can then hedge positions across trading venues.

Under this framework:

- Funds do not need to provide collateral to exchanges or trading partners.

- Counterparty risk is transferred to HRP's balance sheet.

- Trades are recorded under ISDA and standard prime brokerage agreements.

- Clients can margin trade their portfolios across different venues.

Financial Management — Fiat Currency and Stablecoins

In crypto hedge funds (Crypto HF), the financial management function typically involves managing a combination of small fiat currency balances and stablecoin inventories. Once investor subscriptions are accepted, funds are usually converted into stablecoins through fiat on-ramps (exchanges or OTC desks). Considerations for the financial management function include:

Banking Partners

Stablecoins

Banking Partners

Given that most activities are conducted in cryptocurrencies, typically stablecoins, Crypto HFs usually maintain very low fiat currency balances. Nevertheless, all Crypto HFs need to establish banking partnerships to accept investor subscriptions, fund fiat-based expenditures, and pay service providers. The number of banking partners willing to work with crypto clients is steadily increasing, but from an anti-money laundering (AML) and know your customer (KYC) perspective, the account opening process can be cumbersome and often takes months to complete.

Since banks' willingness to work with crypto clients may change based on their respective risk appetites, funds should ideally work with at least two banking partners to ensure redundancy. When Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and Silvergate Bank collapsed, many funds lost their banking partners and were unable to reliably conduct certain operations, including funding redemptions that had been submitted and accepted before these banks' failures.

The account opening process requires a significant amount of documentation, which may be submitted through a portal or directly. From the bank's perspective, the goal of the process is to ensure that the client poses no risk in terms of AML and KYC. To this end, banks will conduct due diligence on the fund structure, its ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs), controlling persons (e.g., directors), and the investment manager. Funds and investment managers with more complex management and ownership structures should be prepared to explain the relationships between the various entities — preparing an organizational chart for this purpose is useful.

Below is a standard set of documents required for the account opening process at U.S. banks. These documents are fairly standard, but they may contain up to 100 fundamental questions related to fund operations, investment managers, all service providers, and potential investors. Additionally, once the account is successfully opened, there is usually ongoing/annual compliance work that may be equivalent to re-opening the account.

Banking Partner Account Opening Document Requirements:

- Account application form

- Due diligence questionnaire

- Company registration certificate — usually requires notarization or certification

- Private placement memorandum

- Company bylaws or limited partnership agreement

- Financial statements

- Board of directors roster

- Business registration excerpt

- W-BEN-E form

- Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) ID — Global Intermediary Identification Number (GIIN)

- U.S. tax identification number

- Passports/drivers' licenses of account signatories and authorized users

- Ultimate beneficial ownership proof

- Passports/drivers' licenses/proofs of residence for all underlying ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs, holding over 10% or 25%)

- Regulatory registration status

- Service agreements with key service providers — fund management, compliance, directors

Stablecoins

Stablecoins are an indispensable part of cryptocurrency trading. However, stablecoins also carry certain operational risks. Stablecoins themselves, particularly USDT/Tether, periodically face "panic" regarding regulation, reserve backing, de-pegging, and the possibility of redemptions being suspended (though this has never occurred). Therefore, it is wise to diversify stablecoin inventories across multiple stablecoins.

Banking partners typically do not impose monthly minimum balance requirements, but they also often do not provide a full suite of services for small fund accounts, including the ability to purchase and hold U.S. Treasury securities. As a result, funds may choose other forms of stablecoins, including Ondo (a tokenized note backed by short-term U.S. Treasury securities and bank deposits) or similar products offered by Centrifuge, which include real-world assets (RWA). Stablecoin products with yields may carry their own risks, and the structure of each stablecoin product should undergo due diligence to properly understand these risks.

Custody

In the crypto space, the term "custody" is metaphorical, as assets do not have a physical form of representation, such as stock certificates.

In traditional finance (TradFi), custody is identity-based, meaning custodians act as agents for the ownership of assets belonging to individuals and corporate entities. In cryptocurrency, custodians act as agents for accessing and controlling private keys.

There are various types of custody for cryptocurrencies, and the appropriate form of custody is typically determined by the investment strategy related to the trading assets and trading frequency. It is likely that multiple types of custody will be implemented simultaneously.

When strategies allow, using third-party custodians is considered preferable, as they provide multiple levels of redundancy and are often scalable. Additionally, as discussed in Section 4, custodians may extend their technology to support tri-party arrangements. A rigorous due diligence process should be employed when selecting third-party custodians. In some cases, some form of self-custody may be required — this may include using hardware wallets and/or smart contract multi-signature wallets.

Custody Policy

It is important to understand the technical differences between various types of custody, as the products of top custodians implement several industry-standard security architectures. The performance record of existing crypto custodians is quite good, with no significant losses occurring, whether systemic or individual; they have withstood various crises unique to the industry. In fact, custodians have benefited from these crises, as investors are increasingly valuing third-party custodians.

Each fund strategy is different, and a complete custody setup may include multiple forms of custody to meet the full needs of the strategy. This process should lead to the creation of a practical custody policy that considers the following factors:

- Trading Assets: Not all custodians support all assets, and ensuring comprehensive asset support may mean working with multiple custodians.

- Trading Frequency: Strategies that implement relatively high-frequency trading may retain some fund assets on exchanges; however, there are now third-party custodians using MPC architecture that also support relatively quick access to assets.

- Diversification and Limits: Similar approaches can be applied to custody as to counterparty management — such limits typically apply to the allocation between types of custody — third-party custody, exchange custody, and self-custody.

- Investor Preferences: Some institutional investors may prefer or require that the majority of fund assets be managed by regulated third-party custodians. However, the best approach should ultimately be determined by the manager on behalf of the investors.

- Internal Resources: For strategies that require teams to use self-custody, these teams should possess the necessary technical expertise and/or access to establish appropriate operational security plans to ensure the proper safeguarding of hardware and recovery phrases. The same applies to teams that primarily rely on third-party custodians — there needs to be a secure and practical method for backing up seed and recovery phrases.

- Recovery Protocols: In all cases, managers must establish protocols for recovering private keys, seeds, and recovery phrases in the event of catastrophic events (including the loss of key personnel). These protocols typically involve a combination of technical and legal measures, including the use of safes and other forms of physical security, as well as designating third-party legal representatives to act on behalf of the fund in disaster situations.

- Access Control: Determine who within the manager's organization, under what circumstances, and by what means can create whitelisted addresses, access assets, and move/extract assets from custody — this includes defining 2FA methods, smartphone usage, and the required number of signatories for multi-signature wallets.

- Asset Isolation and Control: When working with any third party (exchanges, custodians, or other counterparties), it is essential to understand the extent to which assets are legally isolated and belong to the fund, as well as the fund's legal recourse if a counterparty fails.

- Third-Party Oversight: When working with third parties, it is important to understand the extent to which they are subject to oversight by auditors and/or regulatory bodies.

- Regulatory Considerations: The fund may have its own regulatory considerations. Managers based in the U.S. may not be able to use certain custodians in Europe or other regions, and if they wish to do so, they need to design and implement management and ownership structures that allow for this.

- Redundancy: Redundancy for critical services is preferred but not always possible. Opening accounts and maintaining accounts with third-party custodians involves certain overhead and costs, which may not be worthwhile for newly launched managers, but redundancy should be considered where feasible.

The primary consideration in selecting custodians is security. Ultimately, the nature of the underlying assets of the strategy and the trading frequency will determine the custody methods and custodians. For more complex strategies involving multiple trading styles and sub-strategies, multiple custody methods and custodians may be chosen.

The following details the advantages and disadvantages of four main categories of custody:

Self-Custody

Browser-based, software, cold wallets/hardware/offline.

Wide asset support, greater control.

Secure, but requires a very good framework with multi-layer redundancy, coordination, and technical knowledge.

Typically used for assets without third-party support.

Unmanaged

Smart contract custody/multi-signature wallets: Assets are stored in smart contract wallets created and managed by users (e.g., EVM's Safe, Solana's Squads).

More suitable for low turnover strategies rather than high-frequency trading strategies, as moving assets between wallets is operationally more complex.

May involve using hardware to access unmanaged wallets.

Third-Party Custody

Institutional-level.

Clearly defined functions and controls.

May have certain compliance/light regulatory status, such as qualified custodians, and undergo SOC audits; others (like Anchorage) are under the supervision of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC); may have limited insurance coverage.

Responsible for assets, services, and managing complex technology.

Sub-custody, where institutional investors can outsource custody operations to custodians in pooled or segregated account setups (custodians do not know the ultimate investors).

Can be warm wallets, hot wallets, cold wallets (see below).

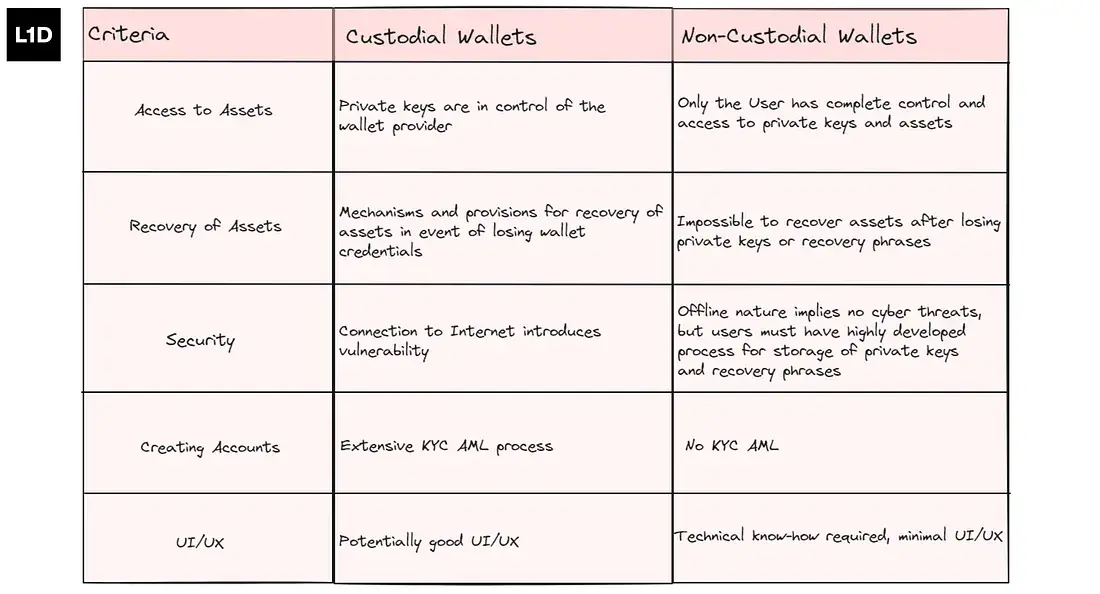

The table below provides a high-level overview of the characteristics of each wallet type.

Third-Party Custodians

These custodians are typically the most technologically advanced, providing complete custody infrastructure and corresponding workflows. Third-party custodians are considered to hold both keys (or parts of key materials) and the assets themselves. Third-party custodians typically employ two architectures:

Multi-Party Computation (MPC)

MPC is a method of combining key shards to sign transactions. It is used when clients wish to hold part of the private key (the "shard" or "share") in addition to the part held by the custodian. This prevents the custodian from abusing the key, making it practically impossible to steal the key from either party, but it also increases the overall responsibility for the proper safeguarding of the key. MPC implements a custody solution where multi-signature requirements replace the need for offline storage of private keys. The shards are geographically and architecturally distributed.

Hardware Security Modules (HSM)

HSMs are hardware that allows for the secure and controlled decryption of private keys. Private keys are generated on the device and cannot be extracted without damaging the device — even to the device holder, the private key is never exposed, cannot be copied, or hacked. HSMs are often marketed as a better form of "cold storage" because they allow for faster decryption of private keys, enabling more real-time access to assets. The main potential drawback of HSMs is that keys are stored in a single central location, which could be used to sign transactions that should not be signed — thus requiring custom business logic that mandates biometric authentication.

This article does not advocate for the superiority of MPC over HSM when selecting third-party custody providers. So far, both have been relatively well-tested and proven to provide sufficient security. In fact, MPC custodians can store each shard in HSM modules, making these technologies complementary.

Opening Accounts with Third-Party Custodians

Working with custodians requires negotiating custody agreements, conducting comprehensive AML/KYC processes, and creating custody vaults. The security measures for interacting with custody vaults are a combination of the custodian's and investment manager's policies, which can form the basis for asset security in investment management operations. The technical and security aspects of working with custodians typically involve the following steps and processes:

- Access and Authentication: Set up secure access to the custodian's platform. This may involve creating strong passwords, enabling two-factor authentication (2FA), defining access controls for authorized personnel, and enabling biometric and video callbacks.

- Testing and Verification: Test the deposit and withdrawal processes with small amounts to ensure everything runs smoothly before handling larger holdings.

- Security Training: Custodians may provide training on how to use their platform securely, including best practices for protecting login credentials and managing assets.

- Asset Transfer: Transfer digital assets to the wallet or address designated by the custodian. This may involve a one-time transfer or a gradual transfer.

- Creating Whitelists and Whitelist Creation Policies: Establish internal policies that dictate who can create and approve whitelists; create and test whitelisted addresses.

- Designating Trading Permissions: For each whitelisted address, specify the types of allowed transactions. Common permissions include:

- Deposits: Allow funds to be deposited into the whitelisted address.

- Withdrawals: Allow withdrawals from the whitelisted address. Set internal withdrawal permissions.

- Transfers: Allow transfers between the whitelisted address and other addresses within the custody solution.

Regulatory Status

More mature custodians typically seek some form of regulatory oversight in the jurisdictions in which they operate. This is positive, as such oversight usually comes with requirements, including undergoing third-party control audits, such as SOC or ISAE (Service Organization Control and International Standards for Assurance Engagements). These audits assess and test the organization's internal control framework. Such audits do not guarantee that custodians are suitable for funds or that they are well-operated businesses; most importantly, they do not imply that security is guaranteed. However, these audits do provide some comfort that custodians have a consistent internal control environment.

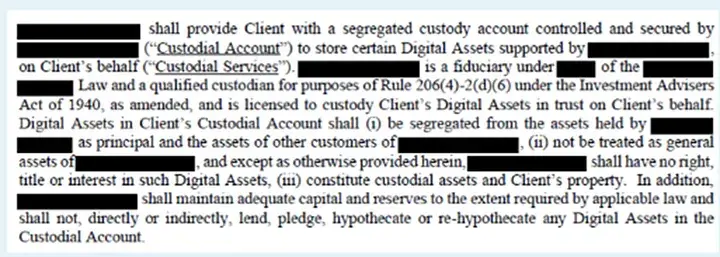

In the U.S., custodians may seek qualified custodian status granted by the SEC or become state-chartered trust companies. In both cases, such custodians are allowed to provide custody services that comply with SEC custody rules, enabling them to act as custodians on behalf of registered investment advisors (RIA). RIAs typically choose to work with qualified custodians or state-chartered trust companies, but they are increasingly collaborating with MPC providers that are not actually qualified custodians, which RIAs and their legal advisors believe is reasonable to operate their funds in a manner that best aligns with their investment strategies. Fireblocks is one such MPC provider that recently launched the Fireblocks Global Custodian Network to address this issue. Fordefi is another similar MPC provider.

Institutional-Level Third-Party Custodians

There are many institutional-level participants, each of which should undergo appropriate due diligence and selection based on its merits. The following institutions are relatively well-known brands, each with its unique characteristics.

Coinbase Custody

Perhaps the most well-known custodian, Coinbase is a New York State-chartered trust company (with a similar structure in Ireland for European clients). As a publicly traded company, it is considered to have relatively good business risk, although client assets are isolated, cannot be re-mortgaged, and are subject to strict scrutiny under public company reporting requirements.

Anchorage Digital

Anchorage is an HSM-based custodian. It is also a nationally chartered qualified custodian in the U.S., supervised by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and holds a limited banking license. Anchorage aims to position itself as the most strictly regulated digital asset custodian in the U.S.

Copper Technologies