Report on the Current Status and Related Costs of Large-Scale Model Training

Author: Jeff Amico

Translation: DeepTechFlow

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Folding@home achieved a major milestone. The research project obtained a computing power of 2.4 exaFLOPS, provided by over 2 million volunteer devices worldwide. This represented fifteen times the processing power of the world's largest supercomputer at the time, enabling scientists to simulate the dynamics of COVID proteins on a large scale. Their work has advanced our understanding of the virus and its pathogenic mechanisms, especially in the early stages of the pandemic.

Global distribution of Folding@home users, 2021

Folding@home, based on volunteer computing, has a long history and aims to solve large-scale problems by crowdsourcing computing resources. This idea gained widespread attention in the 1990s with SETI@home, which gathered over 5 million volunteer computers in the search for extraterrestrial life. Since then, this concept has been applied in various fields including astrophysics, molecular biology, mathematics, cryptography, and gaming. In each case, collective power has enhanced the capabilities of individual projects far beyond what they could achieve alone. This has driven progress, enabling research to be conducted in a more open and collaborative manner.

Many wonder if we can apply this crowdsourcing model to deep learning. In other words, can we train a large-scale neural network among the public? Frontiers in model training represent one of the most computationally intensive tasks in human history. Like many @home projects, the current costs exceed what only the largest participants can bear. This may hinder future progress as we rely on fewer and fewer companies to make new breakthroughs. It also concentrates control of our AI systems in the hands of a few. Regardless of your view on this technology, this is a future worth paying attention to.

Most critics have dismissed the idea of decentralized training as incompatible with current training techniques. However, this view has become increasingly outdated. New technologies have emerged that can reduce communication requirements between nodes, allowing efficient training on devices with poor network connections. These technologies include DiLoCo, SWARM Parallelism, lo-fi, and decentralized training of base models in heterogeneous environments, many of which are fault-tolerant and support heterogeneous computing. There are also new architectures designed specifically for decentralized networks, including DiPaCo and decentralized ensemble of experts models.

We also see various cryptographic primitives maturing, enabling networks to coordinate resources globally. These technologies support applications such as digital currency, cross-border payments, and prediction markets. Unlike early volunteer projects, these networks can aggregate astonishing computing power, often several orders of magnitude larger than the currently envisioned largest cloud training clusters.

These elements together constitute a new paradigm for model training. This paradigm fully leverages global computing resources, including a large number of edge devices that can be utilized if connected. This will reduce the cost of most training workloads by introducing new competitive mechanisms. It can also unlock new forms of training, making model development more collaborative and modular rather than isolated and singular. Models can access computing and data from the public for real-time learning. Individuals can own a part of the models they create. Researchers can also publicly share novel research findings without having to monetize their discoveries to cover high computational budgets.

This report examines the current status and related costs of large-scale model training. It reviews past distributed computing efforts—from SETI to Folding to BOINC—as inspiration to explore alternative paths. The report discusses the historical challenges of decentralized training and turns to the latest breakthroughs that may help overcome these challenges. Finally, it summarizes the opportunities and challenges for the future.

Current Status of Frontiers in Model Training

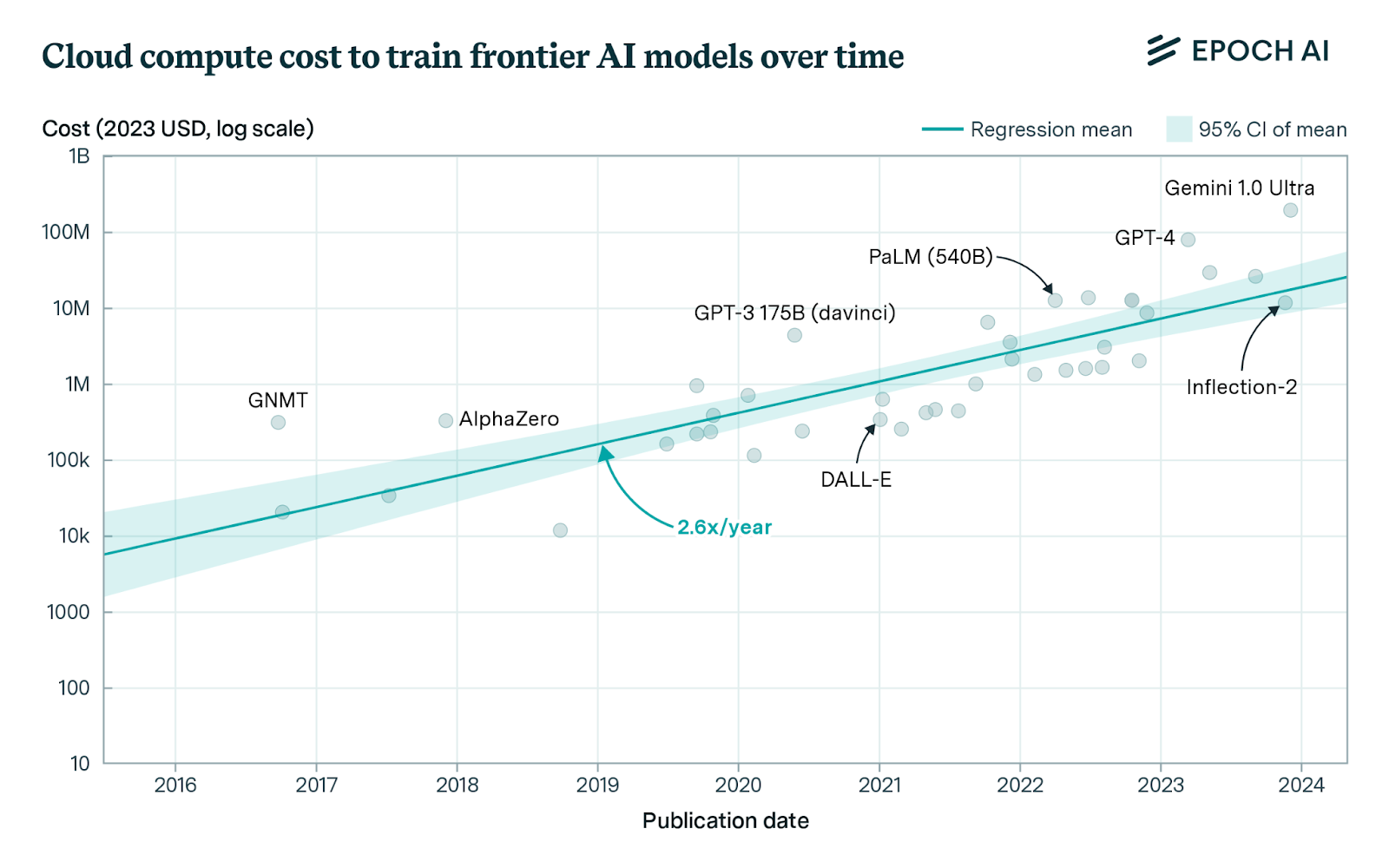

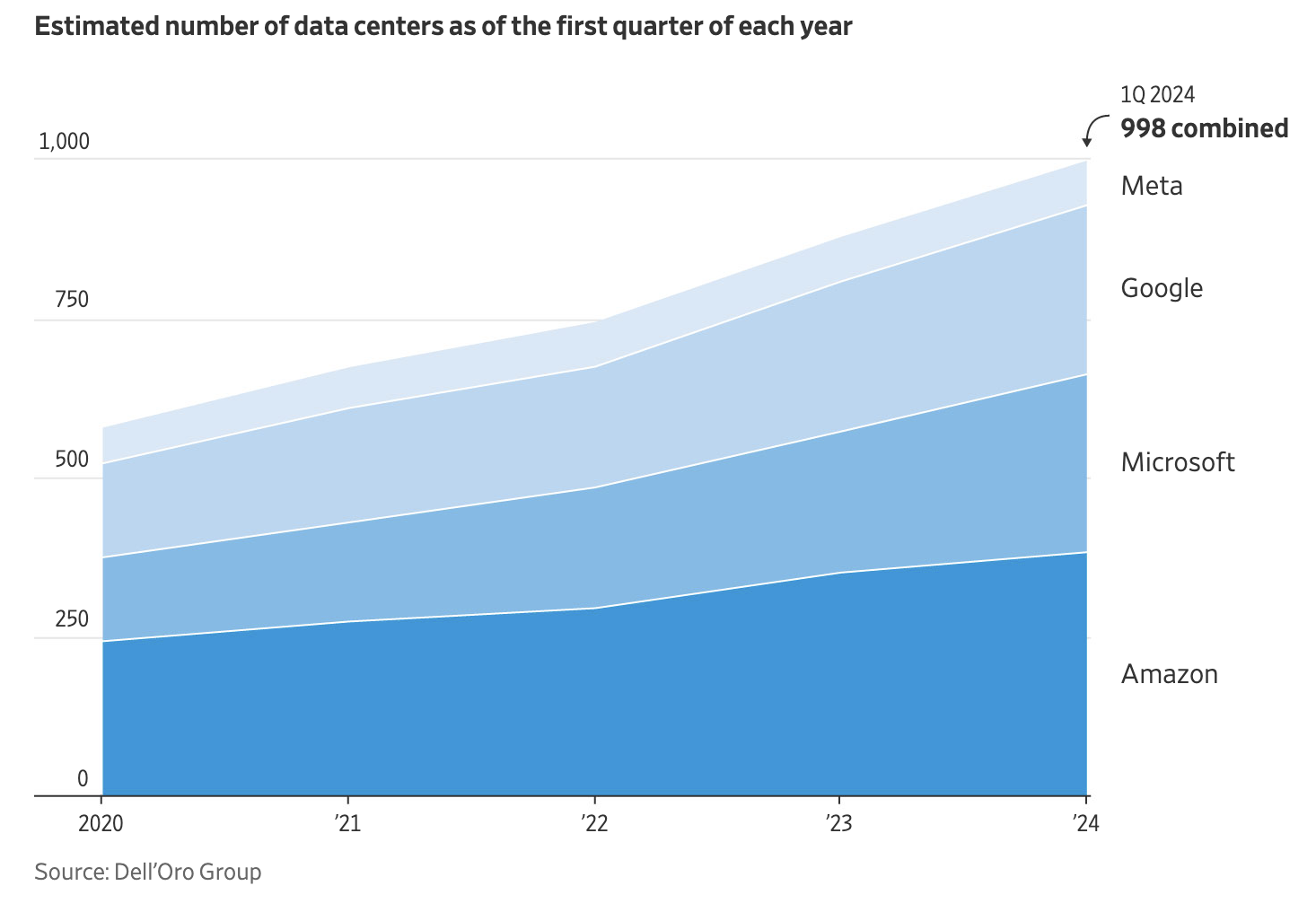

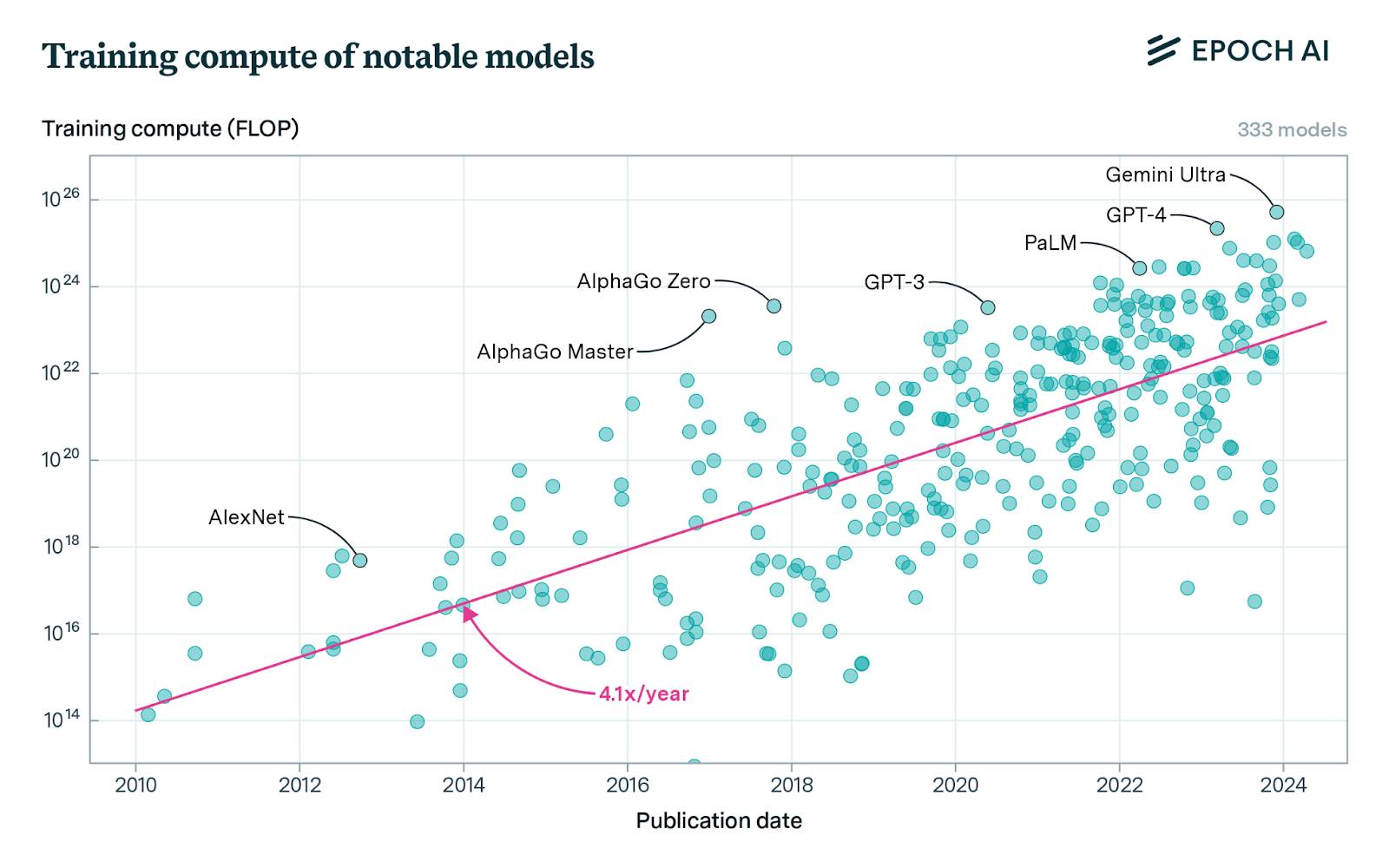

The cost of frontiers in model training has become unaffordable for non-major participants. This trend is not new, but according to the actual situation, it is becoming more severe as frontier labs continuously challenge the scaling hypothesis. Reportedly, OpenAI spent over $3 billion on training this year. Anthropic predicts that by 2025, we will start training with $10 billion, and a $100 billion model is not too far off.

This trend has led to industry centralization as only a few companies can afford the participation costs. This raises core policy questions for the future—can we accept a situation where all leading AI systems are controlled by one or two companies? It also limits the pace of progress, which is evident in the research community as smaller labs cannot afford the computational resources needed for scaling experiments. Industry leaders have also mentioned this multiple times:

Meta's Joe Spisak: To truly understand the capabilities of [models] architecture, you have to explore at scale, which I think is missing in the current ecosystem. If you look at academia—there's a lot of great talent in academia, but they lack access to computational resources, and that becomes a problem because they have these great ideas, but they don't have a way to really realize those ideas at the level they need to.

Together's Max Ryabinin: The demand for expensive hardware puts a lot of pressure on the research community. Most researchers cannot participate in the development of large neural networks because the necessary experiments are too costly for them. If we continue to increase the size of models by scaling them up, eventually we will be able to compete.

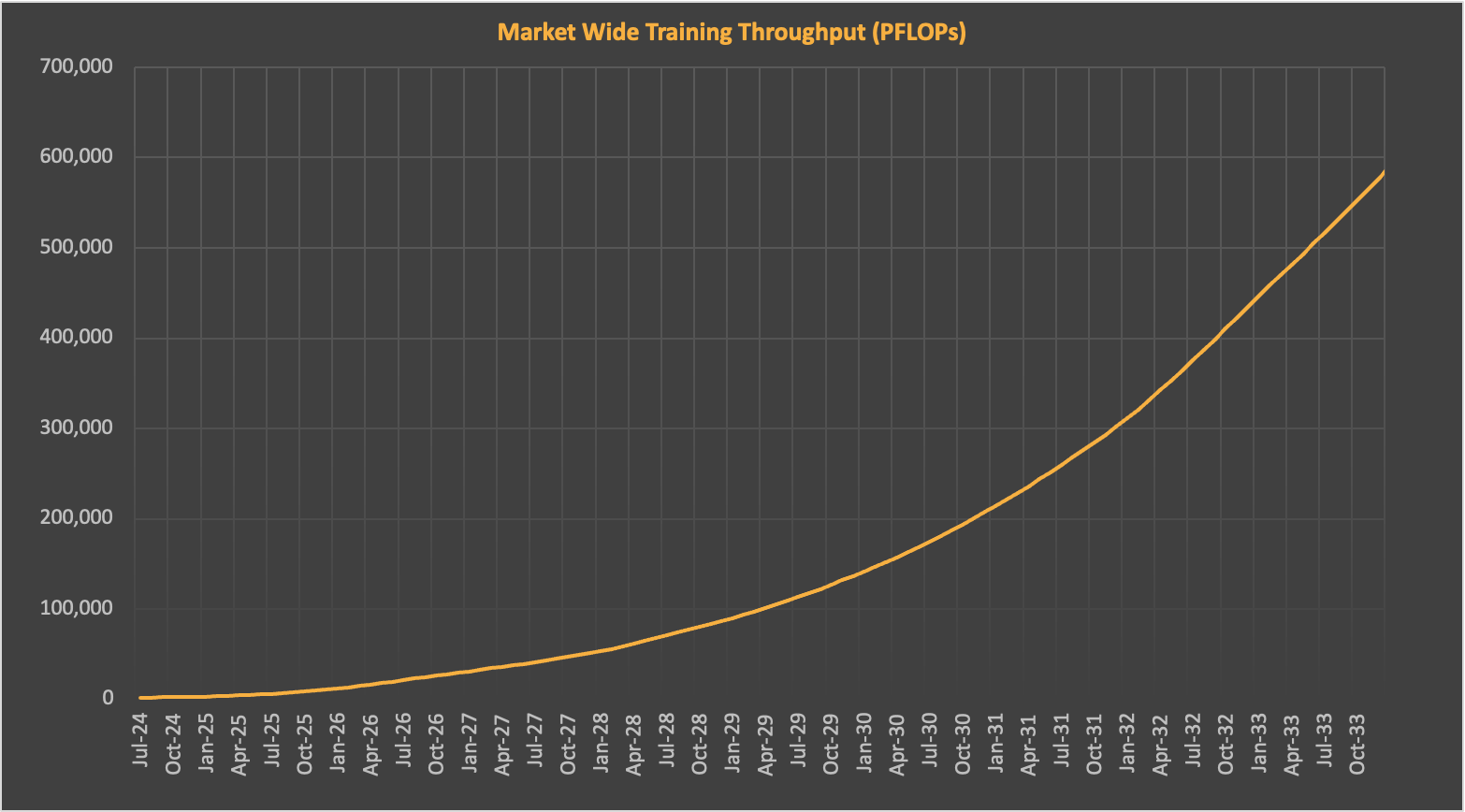

Google's Francois Chollet: We know that large language models (LLMs) have not yet achieved general artificial intelligence (AGI). Meanwhile, progress towards AGI has stalled. The limitations we face with large language models today are exactly the same as the limitations we faced five years ago. We need new ideas and breakthroughs. I think the next breakthrough is likely to come from external teams, while all the large labs are busy training even larger language models. Some are skeptical of these concerns, believing that hardware improvements and capital expenditure on cloud computing will solve the problem. But this seems unrealistic. On one hand, by the end of this decade, the number of FLOPs in the next generation of Nvidia chips will increase significantly, possibly reaching 10 times that of today's H100. This will reduce the price per FLOP by 80-90%. Similarly, it is expected that by the end of this decade, the total FLOP supply will increase by about 20 times, while improving networks and related infrastructure. All of this will increase the training efficiency per dollar.

At the same time, the total FLOP demand will also increase significantly as labs hope to further scale. If the training compute trend continues for a decade, the FLOPs required for frontier training are expected to reach about 2e29 by 2030. Training at this scale would require approximately 20 million H100 equivalent GPUs, based on current training runtimes and utilization rates. Assuming there are still multiple frontier labs in this field, the total FLOP demand will be several times this number, as the overall supply will be distributed among them. EpochAI predicts that by then we will need approximately 100 million H100 equivalent GPUs, about 50 times the 2024 shipment volume. SemiAnalysis also made similar predictions, suggesting that frontier training demand and GPU supply will roughly grow in sync during this period.

Capacity constraints may become more acute for various reasons. For example, if manufacturing bottlenecks delay expected shipment cycles, this situation is common. Or if we fail to produce enough energy to power data centers. Or if we encounter difficulties in connecting these energy sources to the grid. Or if increasing scrutiny of capital expenditure ultimately leads to industry downsizing, and other factors. In the best case, our current approach can only allow a few companies to continue driving research progress, which may not be enough.

Clearly, we need a new approach. This approach does not require constantly expanding data centers, capital expenditure, and energy consumption to find the next breakthrough, but efficiently utilizes our existing infrastructure and can flexibly expand with demand fluctuations. This will allow for more experiments in research, as training runs no longer require the investment return of a multi-million dollar computing budget. Once freed from this constraint, we can surpass the current large language model (LLM) paradigm, as many believe achieving general artificial intelligence (AGI) is necessary. To understand what this alternative might look like, we can draw inspiration from past distributed computing practices.

Volunteer Computing: A Brief History

SETI@home popularized this concept in 1999, allowing millions of participants to analyze radio signals in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. SETI collected electromagnetic data from the Arecibo telescope, divided it into batches, and sent it to users over the internet. Users analyzed the data in their daily activities and sent back the results. There was no need for communication between users, and batches could be independently verified, enabling highly parallel processing. At its peak, SETI@home had over 5 million participants and processing power exceeding that of the largest supercomputers at the time. It ultimately shut down in March 2020, but its success inspired subsequent volunteer computing movements.

Folding@home continued this concept in 2000, using edge computing to simulate protein folding in diseases such as Alzheimer's, cancer, and Parkinson's. Volunteers conducted protein simulations on their personal computers during idle time, helping researchers study how proteins misfold and lead to diseases. At different times in its history, its computing power surpassed that of the largest supercomputers, including in the late 2000s and during the COVID period, when it became the first distributed computing project to exceed one exaFLOPS. Since its inception, Folding's researchers have published over 200 peer-reviewed papers, all relying on the computing power of volunteers.

The Berkeley Open Infrastructure for Network Computing (BOINC) popularized this concept in 2002, providing a crowdsourced computing platform for various research projects. It supports multiple projects including SETI@home and Folding@home, as well as new projects in fields such as astrophysics, molecular biology, mathematics, and cryptography. By 2024, BOINC listed 30 ongoing projects and nearly 1,000 published scientific papers, all utilizing its computing network.

Outside of the research field, volunteer computing has been used to train game engines for Go (LeelaZero and KataGo) and chess (Stockfish and LeelaChessZero). LeelaZero was trained through volunteer computing from 2017 to 2021, enabling it to play over ten million games against itself and becoming one of the strongest Go engines today. Similarly, Stockfish has been continuously trained on volunteer networks since 2013, making it one of the most popular and powerful chess engines.

Challenges in Deep Learning

But can we apply this model to deep learning? Can we network edge devices around the world to create a low-cost public training cluster? Consumer hardware—from Apple laptops to Nvidia gaming cards—is becoming increasingly powerful in deep learning performance, often surpassing the performance of data center GPUs in many cases, including in terms of performance and 3-slot design and power issues.

However, to effectively utilize these resources in a distributed environment, we need to overcome various challenges.

First, current distributed training techniques assume frequent communication between nodes.

The most advanced models have become so large that training must be split among thousands of GPUs. This is achieved through various parallelization techniques, often splitting the model, dataset, or both across available GPUs. This typically requires a high-bandwidth and low-latency network, or else nodes will be idle, waiting for data to arrive.

For example, Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) technique distributes the dataset across GPUs, with each GPU training the complete model on its specific data slice and then sharing its gradient updates to generate new model weights at each step. This requires relatively limited communication overhead, as nodes only share gradient updates after each backward pass, and collective communication operations can partially overlap with computation. However, this approach is only suitable for smaller models, as it requires each GPU to store the entire model's weights, activations, and optimizer state in memory. For example, GPT-4 requires over 10TB of memory during training, while a single H100 has only 80GB.

To address this issue, we also use various techniques to split the model for allocation across GPUs. For example, tensor parallelism splits individual weights within a single layer, allowing each GPU to perform necessary operations and pass the output to other GPUs. This reduces the memory requirements for each GPU but requires continuous communication between them, thus requiring high-bandwidth, low-latency connections for efficiency.

Pipeline parallelism allocates layers of the model to different GPUs, with each GPU performing its work and sharing updates with the next GPU in the pipeline. While this requires less communication than tensor parallelism, it may lead to "bubbles" (e.g., idle time), where GPUs further down the pipeline wait for information from preceding GPUs to start their work.

To address these challenges, various technologies have been developed. For example, ZeRO (Zero Redundancy Optimizer) is a memory optimization technique that reduces memory usage by increasing communication overhead, enabling larger models to be trained on specific devices. ZeRO reduces memory requirements by partitioning model parameters, gradients, and optimizer states across GPUs, but relies on extensive communication for devices to access the partitioned data. It forms the basis for popular technologies such as Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) and DeepSpeed.

These techniques are often combined in large model training to maximize resource utilization efficiency, known as 3D parallelism. In this configuration, tensor parallelism is typically used to distribute weights across GPUs within a single server, as there is significant communication required between each partitioned layer. Then, pipeline parallelism is used to allocate layers across different servers (but within the same data center island), as it requires less communication. Subsequently, data parallelism or Fully Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) is used to split the dataset across different server islands, as it can adapt to longer network latencies through asynchronous sharing of updates and/or gradient compression. Meta uses this combined approach to train Llama 3.1, as illustrated in the diagram below.

These methods present core challenges for decentralized training networks, which rely on devices connected via (slower and more fluctuating) consumer-grade internet connections. In this environment, communication costs quickly outweigh the benefits of edge computing, as devices are often idle, waiting for data to arrive. For example, in a simple scenario, distributed data parallel training of a half-precision model with 1 billion parameters requires each GPU to share 2GB of data at each optimization step. Using typical internet bandwidth (e.g., 1 gigabit per second) as an example, assuming computation and communication do not overlap, transmitting gradient updates would take at least 16 seconds, resulting in significant idle time. Technologies like tensor parallelism (which require more communication) would perform even worse.

Secondly, current training techniques lack fault tolerance. Like any distributed system, as the scale increases, training clusters become more prone to failures. However, this issue is more severe in training because our current technologies are primarily synchronous, meaning GPUs must work together to complete model training. The failure of a single GPU among thousands can cause the entire training process to halt, forcing other GPUs to start training from scratch. In some cases, GPUs do not completely fail but become slow for various reasons, thereby slowing down the thousands of other GPUs in the cluster. Considering the scale of today's clusters, this could mean additional costs in the tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars.

Meta detailed these issues in their Llama training process, experiencing over 400 unexpected interruptions, averaging about 8 interruptions per day. These interruptions were mainly attributed to hardware issues, such as GPU or host hardware failures. This resulted in their GPU utilization being only 38-43%. OpenAI performed even worse during the training of GPT-4, at 32-36%, also due to frequent failures during training.

In other words, cutting-edge labs struggle to achieve utilization rates of 40% even in fully optimized environments (including homogeneous, state-of-the-art hardware, networking, power, and cooling systems). This is mainly due to hardware failures and network issues, which would be more severe in edge training environments due to the imbalance in processing power, bandwidth, latency, and reliability. Not to mention, decentralized networks are vulnerable to malicious actors who may attempt to disrupt the overall project or cheat on specific workloads for various reasons. Even the purely volunteer network SETI@home has experienced cheating by different participants.

Third, cutting-edge model training requires massive computational power. While projects like SETI and Folding have achieved impressive scales, they pale in comparison to the computational power required for today's cutting-edge training. GPT-4 was trained on a cluster of 20,000 A100s, with a peak throughput of 6.28 ExaFLOPS in half-precision. This is three times more powerful than Folding@home at its peak. Llama 405b was trained using 16,000 H100s, with a peak throughput of 15.8 ExaFLOPS, which is 7 times the peak of Folding. With multiple labs planning to build clusters of over 100,000 H100s, this gap will only widen, with each cluster's computational power reaching a staggering 99 ExaFLOPS.

This makes sense, as @home projects are volunteer-driven. Contributors donate their memory and processor cycles and bear the associated costs. This naturally limits their scale relative to commercial projects.

Recent Developments

While these issues have historically plagued decentralized training efforts, they seem no longer insurmountable. New training techniques have emerged that can reduce communication requirements between nodes, enabling efficient training on internet-connected devices. Many of these technologies originate from large labs that aim to scale up model training, thus requiring efficient communication technologies across data centers. We have also seen progress in fault-tolerant training methods and incentive systems for encryption, which can support larger-scale training in edge environments.

Efficient Communication Technologies

DiLoCo is a recent research from Google that reduces communication overhead by locally optimizing the model state updates before passing them between devices. Their method (based on early federated learning research) shows comparable performance to traditional synchronous training while reducing communication between nodes by 500 times. Since then, this method has been replicated by other researchers and extended to train larger models (over 10 billion parameters). It has also been extended to asynchronous training, meaning nodes can share gradient updates at different times rather than all at once. This better adapts to the varying processing power and network speeds of edge hardware.

Other data parallel methods, such as lo-fi and DisTrO, aim to further reduce communication costs. Lo-fi proposes a fully local fine-tuning method, where nodes train independently and only pass weights at the end. This method performs comparably to the baseline when fine-tuning language models with over 10 billion parameters, while completely eliminating communication overhead. In a preliminary report, DisTrO claims to have adopted a new distributed optimizer that they believe can reduce communication requirements by four to five orders of magnitude, although this method is yet to be confirmed.

New model parallel methods have also emerged, making it possible to achieve larger scales. DiPaCo (also from Google) partitions the model into multiple modules, each containing different expert modules for training specific tasks. Then, the training data is sharded through "paths," which are sequences of experts corresponding to each data sample. Given a shard, each worker can train specific paths almost independently, except for the communication required to share the shared modules, which is handled by DiLoCo. This architecture reduces training time for billion-parameter models by over half.

SWARM Parallelism and Decentralized Training of Basic Models in Heterogeneous Environments (DTFMHE) also propose model parallel methods to achieve large-scale training in heterogeneous environments. SWARM finds that as the model scale increases, pipeline parallelism communication constraints decrease, enabling effective training of larger models with lower network bandwidth and higher latency. To apply this concept in a heterogeneous environment, they use temporary "pipeline connections" between nodes, which can be updated in real-time at each iteration. This allows nodes to send their output to any peer node in the next pipeline stage. This means that if a peer node is faster than others, or if any participant disconnects, the output can be dynamically rerouted to ensure training continues, as long as each stage has at least one active participant. They used this method to train a billion-parameter model on low-cost heterogeneous GPUs, despite slow interconnect speeds (as shown in the figure below).

DTFMHE also proposes a novel scheduling algorithm, as well as pipeline and data parallelism, to train large models on devices across 3 continents. Despite their network speed being 100 times slower than standard Deepspeed, their method is only 1.7-3.5 times slower than using standard Deepspeed in a data center. Similar to SWARM, DTFMHE shows that as the model scale increases, communication costs can be effectively hidden, even in geographically distributed networks. This allows us to overcome weaker connections between nodes through various technologies, including increasing the size of hidden layers and adding more layers to each pipeline stage.

Fault Tolerance

Many of the aforementioned data parallel methods inherently have fault tolerance, as each node stores the entire model in memory. This redundancy typically means that nodes can continue to work independently even if other nodes fail. This is crucial for decentralized training, as nodes are often unreliable, heterogeneous, and may even be malicious. However, as mentioned earlier, pure data parallel methods are only suitable for smaller models, so model size is constrained by the smallest node's memory capacity in the network.

To address the above issues, some have proposed fault-tolerant techniques for model parallel (or mixed parallel) training. SWARM addresses peer node failures by prioritizing stable peer nodes with lower latency and rerouting pipeline stage tasks in case of failure. Other methods, such as Oobleck, employ similar approaches by creating multiple "pipeline templates" to provide redundancy to handle partial node failures. While tested in data centers, Oobleck's method provides strong reliability guarantees, which also apply to decentralized environments.

We have also seen new model architectures, such as Decentralized Mixture of Experts (DMoE), designed to support fault-tolerant training in decentralized environments. Similar to traditional Mixture of Experts models, DMoE consists of multiple independent "expert" networks distributed across a group of worker nodes. DMoE uses a distributed hash table to track and integrate asynchronous updates in a decentralized manner. This mechanism (also used in SWARM) exhibits good resistance to node failures, as it can exclude certain experts from the average computation if some nodes fail or are unresponsive.

Scalability

Finally, incentive systems like those adopted by Bitcoin and Ethereum can help achieve the required scale. These networks crowdsource computation by paying contributors in a local asset that appreciates with adoption. This design incentivizes early contributors by rewarding them handsomely, with these rewards gradually decreasing as the network reaches minimum viable scale.

Indeed, this mechanism has various pitfalls that need to be avoided. The most significant pitfall is over-incentivizing supply without corresponding demand. Additionally, if the underlying network is not sufficiently decentralized, it may raise regulatory issues. However, when designed properly, decentralized incentive systems can achieve considerable scale over time.

For example, Bitcoin's annual electricity consumption is approximately 150 terawatt-hours (TWh), which is two orders of magnitude higher than the projected power consumption of the largest AI training cluster (100,000 H100s running at full load for a year). For reference, OpenAI trained GPT-4 on 20,000 A100s, and Meta's flagship Llama 405B model was trained on 16,000 H100s. Similarly, Ethereum's power consumption is approximately 70 TWh at its peak, spread across millions of GPUs. Even considering the rapid growth of AI data centers in the coming years, incentive computing networks like these will still surpass their scale multiple times.

Certainly, not all computations are interchangeable, and the unique requirements of training relative to mining need to be considered. Nonetheless, these networks demonstrate the scale that can be achieved through these mechanisms.

Future Pathways

Connecting these pieces together, we can see the beginning of new pathways forward.

Soon, new training technologies will enable us to surpass the limitations of data centers, as devices no longer need to be colocated to be effective. This will take time, as our current decentralized training methods are still at a relatively small scale, primarily in the range of 1 to 2 billion parameters, much smaller than models like GPT-4. We need further breakthroughs to scale up these methods without sacrificing critical attributes like communication efficiency and fault tolerance. Alternatively, we need new model architectures that are different from today's large monolithic models—possibly smaller, more modular, and running on edge devices rather than in the cloud.

In any case, it is reasonable to expect further progress in this direction. The cost of our current methods is unsustainable, providing strong market incentives for innovation. We have already seen this trend, with manufacturers like Apple building more powerful edge devices to run more workloads locally rather than relying on the cloud. We also see increasing support for open-source solutions—even within companies like Meta, to promote more decentralized research and development. These trends will only accelerate over time.

Meanwhile, we also need new network infrastructure to connect edge devices to enable their use in this way. These devices include laptops, gaming consoles, and eventually even smartphones with high-performance GPUs and large memory. This will allow us to build a "global cluster" of low-cost, always-on computing power that can parallelize training tasks. This is also a challenging problem that requires progress in multiple domains.

We need better scheduling techniques for training in heterogeneous environments. Currently, there is no method to automatically parallelize models for optimization, especially when devices can disconnect or connect at any time. This is a critical next step for optimizing training while retaining the scale advantage based on edge networks.

We also need to address the general complexity of decentralized networks. To maximize scale, networks should be built as open protocols—a set of standards and instructions governing interactions between participants, much like TCP/IP for machine learning computation. This would allow any device following specific specifications to connect to the network, regardless of owner and location. It also ensures the network remains neutral, allowing users to train the models they prefer.

While this achieves maximization of scale, it also requires a mechanism to verify the correctness of all training tasks without relying on a single entity. This is crucial because there are inherent incentives for cheating—for example, claiming to have completed a training task to receive rewards when it has not actually been done. Considering that different devices typically perform machine learning operations in different ways, using standard replication techniques becomes challenging to verify correctness, making it particularly challenging. Properly addressing this issue requires in-depth research in cryptography and other disciplines.

Fortunately, we continue to see progress in all these areas. These challenges seem less insurmountable compared to the past few years. They also appear quite small in comparison to the opportunities. Google provides the best summary of this in their DiPaCo paper, pointing out the potential for decentralized training to break the negative feedback loop:

Progress in distributed training of machine learning models may lead to simplified infrastructure construction, ultimately resulting in more widely available computing resources. Currently, infrastructure is designed around the standard approach of training large monolithic models, while the architecture of machine learning models is also designed to leverage current infrastructure and training methods. This feedback loop may lead the community into a misleading local minimum, where the limitations of computing resources exceed actual needs.

Perhaps most exciting is the increasing enthusiasm in the research community to address these issues. Our team at Gensyn is building the aforementioned network infrastructure. Teams like Hivemind and BigScience have been applying many of these technologies in practice. Projects like Petals, sahajBERT, and Bloom demonstrate the capabilities of these technologies and the growing interest in community-based machine learning. Many others are also driving research progress with the goal of building a more open, collaborative model training ecosystem. If you are interested in this work, please contact us to get involved.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。