Title: "Value accrual for Rollup frameworks and RaaS (are they going to ZERO?)"

Author: StackrLabs

Translation: Yvonne, MarsBit

If the future is a chain economy composed of thousands of Rollups, then we are undoubtedly on the right timeline. From the Optimism stack and Polygon chain development kit to Caldera and Stackr, various Rollup frameworks and Rollup as a Service (RaaS) providers have emerged in the market in recent months. These frameworks provide modular (often open-source) code libraries for different components of Rollup, allowing developers to choose custom options from each layer of the stack.

However, how do these providers accrue value? NeelSomani (founder of Eclipse) recently delivered a speech titled "RaaS Solutions Are Going to Zero" at the Modular Summit.

In this blog post, we will analyze some of his arguments and explore the complex dynamics of value accrual for Rollup frameworks and RaaS providers. From individual layers to Superchain, we will uncover the hidden mechanisms behind the creation and accrual of value for Rollup frameworks and RaaS providers.

Rollup vs Rollup Framework vs RaaS

Rollup is an application that executes off-chain and publishes execution data to another blockchain. In this way, they can obtain the security properties of the main chain. The Rollup application itself can be a single state transition function or an independent blockchain, with its state specified by a set of nodes.

A Rollup framework is a pre-built code library that implements the basic components of Rollup. Developers can use these existing code libraries (often packaged as SDKs) and customize them according to their specific needs, rather than building Rollup from scratch. Examples of open-source Rollup frameworks include OPStack and ArbitrumOrbit.

Rollup as a Service (or RaaS protocol) is a no-code wrapper built on top of existing Rollup frameworks. Developers can quickly deploy Rollup from scratch by selecting custom features from a dropdown menu. RaaS companies typically sort and provide additional consulting services for the deployed Rollup.

Flow of Funds

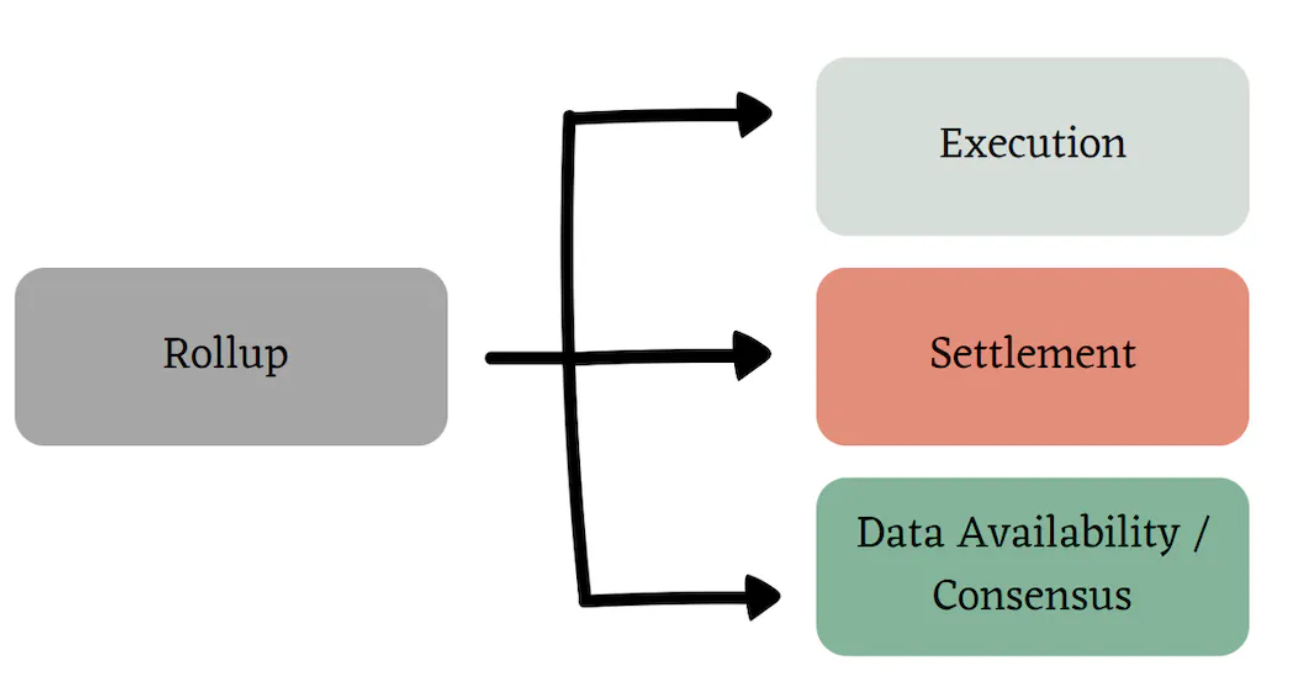

To understand the value inflow and outflow of the entire stack, it is necessary to first understand the architecture of Rollup and the interactions between different layers. There are roughly three levels that make up the Rollup stack:

- Execution - This layer executes transactions by applying state transition functions (STFs) on the existing state of Rollup. The responsibilities of the execution nodes are wide-ranging, from issuing transaction instructions, executing transactions, to publishing transactions on L1, and creating fraud/validity proofs, depending on the "centralization" level of Rollup.

The execution layer is the "customer-facing" layer and is where funds enter the Rollup stack. Users need to pay transaction fees (gas), which are typically the difference between various costs that the execution layer needs to pay (detailed later). This layer can also extract additional value from users through some means (also known as MEV: maximum extractable value) by sorting transactions.

- Settlement - This includes validating fraud/validity proofs and "defining" the canonical state of Rollup (in the case of smart contract Rollup). Settlement is typically managed by a unified high-security layer (such as Ethereum). Rollup frameworks can also build their own settlement layer.

Since validation costs are usually low, settlement is not a high-value stack layer. Optimism only needs to pay about $5 in settlement fees to Ethereum per day. The cost of a competitive settlement layer is even lower (as emphasized in the article "Rollups-as-a-Service Are Going to Zero").

- Data Availability - DA involves broadcasting sorted transaction data to other parts of the network (sometimes also called data publishing). It ensures that anyone can rebuild the Rollup state without permission by simply applying the broadcasted transaction data to the previously finalized state.

DA costs are a major part of all Rollup costs. Publishing data on a highly secure layer like Ethereum can be quite expensive. Protocols such as Celestia, Avail, and EigenDA are actively developing cheaper and faster DA alternatives. Rollup frameworks can also consider building their own DA layer, but decentralized DAs incur high bootstrap costs and make interoperability more complex.

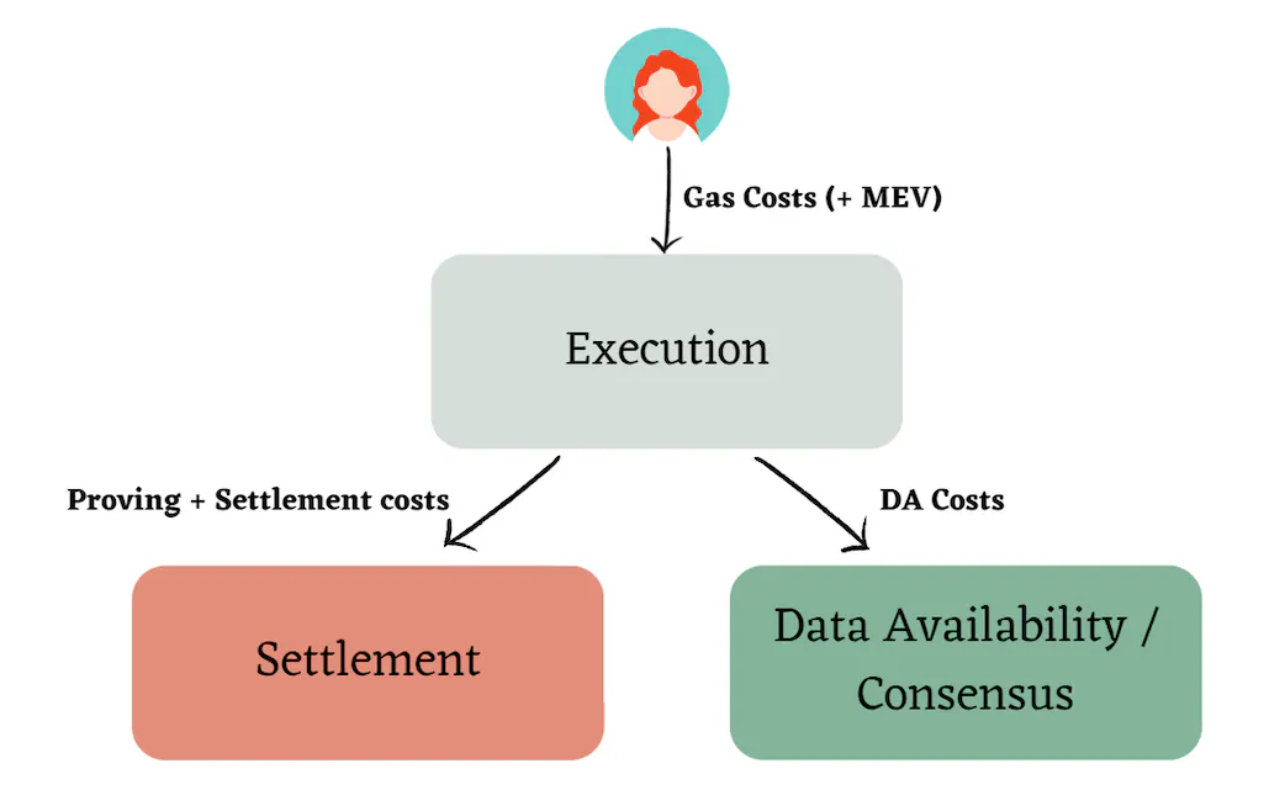

Viewing the execution layer as a B2C model and the settlement layer and DA layer as a B2B model may be helpful:

The execution layer purchases block space from the DA layer and directly sells its execution services to end users (customers), and purchases verification and bridging services from the settlement layer;

The DA layer sells block space to the execution layer;

The settlement layer provides settlement services to the execution layer.

In a competitive market environment, most of the value capture comes directly from the execution layer of the stack, so further dissecting and independently analyzing its value flow makes sense.

Execution Layer: B2C Economic Model

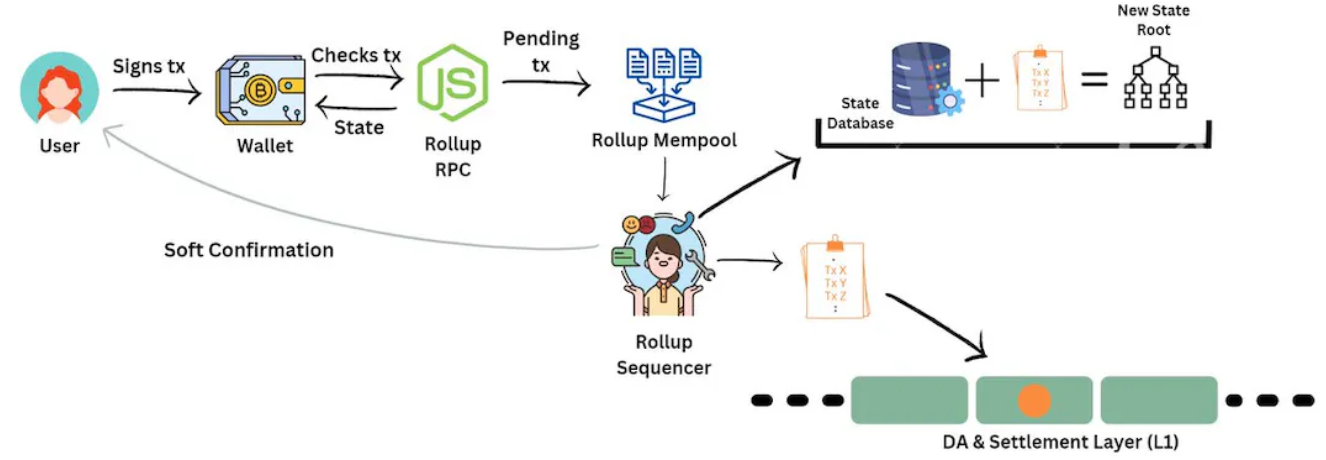

The execution layer generates revenue by charging fees for each transaction from users and pays operational costs to other businesses (layers) in the stack.

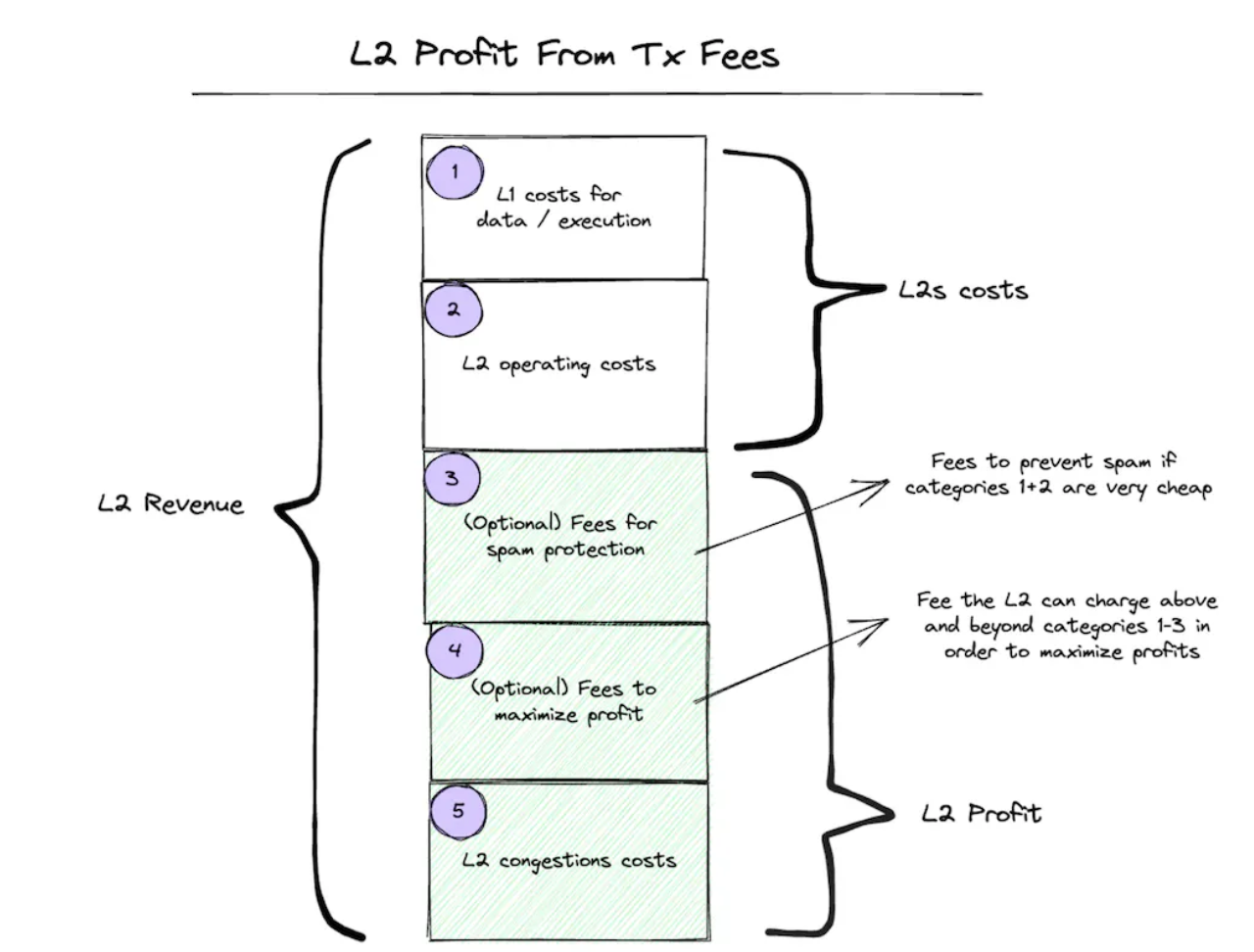

Revenue: Inflowing value can be divided into the following categories:

Gas fees paid by end users for each transaction;

On-chain MEV;

Cross-chain MEV (if the framework provides sorting for multiple Rollups on the same DA layer, otherwise it may be difficult to extract).

MEV depends on transaction flows (the "extractable" value of each group of transactions is different) and is often difficult to predict in advance. Therefore, the gas fees charged to users are usually higher than the overall predictable costs.

Costs: Outflowing value from the execution layer includes:

Node operating expenses

Execution (computing) costs

Proof (validity/fraud proof) costs

Data publishing costs (varies based on congestion of the DA layer)

In most cases, all responsibilities of the execution layer are borne by a centralized sequencer node. This single node receives all income from users and is responsible for paying DA and settlement fees. In other cases, different nodes can be set up to take on different responsibilities:

Sequencers sort transactions and publish data on the DA layer. They "earn" transaction fees paid by users and pay sorting expenses and data publishing costs. Sorting work can also be done by a group of pre-selected sequencers or decentralized sequencers like Espresso. Sequencers are also responsible for publishing state changes to the settlement layer and paying settlement costs.

Prover nodes are responsible for generating proofs. It can be a centralized prover or a group of decentralized prover nodes. Their costs include the expense of generating proofs. Depending on the settings, provers either "sell" proofs to sequencers or publish them directly to the settlement layer.

Rollup can also have other full nodes (or full verification light nodes) to execute all transaction batches and maintain the canonical state of Rollup. These full nodes may not generate any direct income, but indirectly capture value by holding the native Gas token of Rollup.

The above is a rough distinction of the responsibilities of different nodes. The allocation of tasks to different nodes depends on the architectural settings of the Rollup team. For simplicity in this article, we will stick to the setting of a centralized sequencer, where one node performs all necessary execution tasks.

So the question is: if the execution layer can bring the most value, which participant in the stack is most capable of capturing this value?

Anyone running a sequencer node and performing various activities related to it!

This can be the Rollup team itself. Or, as mentioned at the beginning of the article, RaaS providers often handle sorting for the Rollup they deploy. In fact, this is the main part of RaaS provider income.

How Does RaaS Make Money?

RaaS can capture value in three main areas:

Sequencer hosting: RaaS providers are responsible for running sequencers and related activities. This is a division of labor, where the promotion team brings innovation (the applications they are building), and RaaS providers are responsible for everything else. Sequencers sort transactions, publish data on L1, and create proofs when needed.

Additional infrastructure: block explorers, bridges, etc.

Dedicated support: consulting and cooperation on infrastructure decisions (such as sorting, MEV, etc.) + other technical support

RaaS is similar to traditional B2B SaaS businesses, where companies can charge customers a unified fee or a hybrid tiered fee based on the services purchased and usage (e.g., the number of end-user transactions for Rollup).

RaaS can also provide integrations with shared sequencers like Espresso. However, in this case, they would lose sequencer income, which is the main part of RaaS profits. Therefore, these partnerships require shared sequencers and RaaS providers to share profits through contracts.

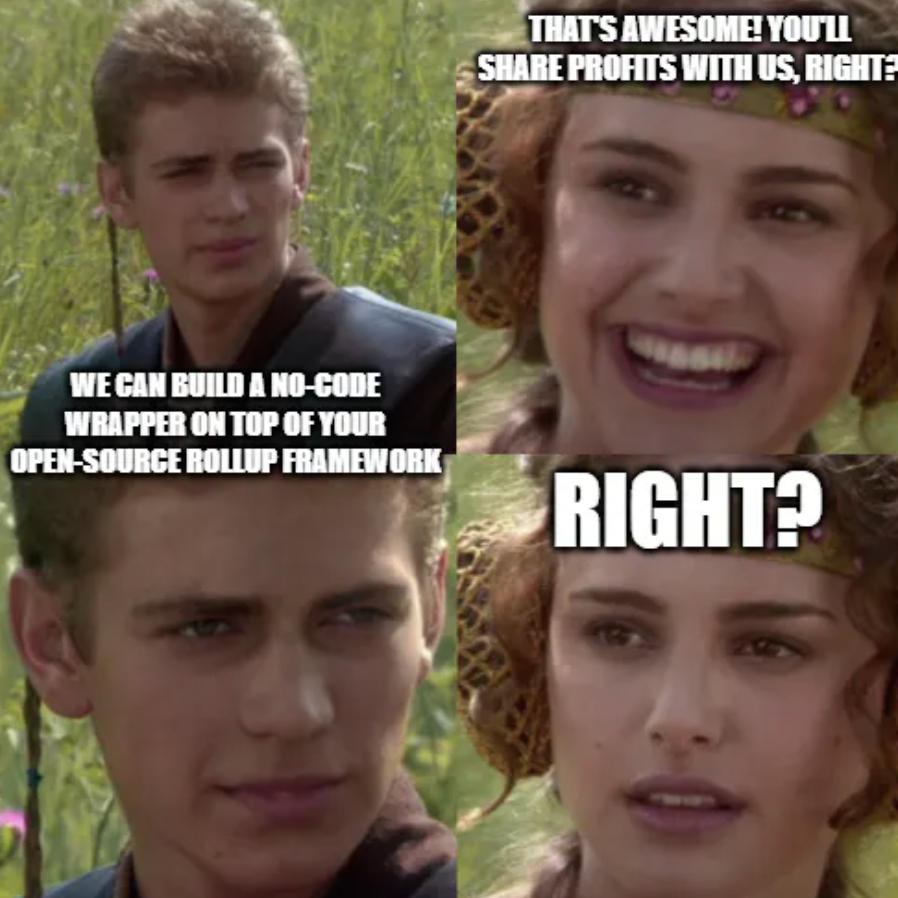

But if RaaS is a wrapper built on top of existing Rollup frameworks, then it must also share revenue with them, right?

Not necessarily.

So far, most of the released Rollup frameworks have been open-source and do not allow building on top of them. RaaS providers can use the framework without permission to build a no-code wrapper on top of it and are not obligated to share any profits with the underlying framework.

Can they sign profit-sharing agreements with Rollup frameworks?

They can, but if they do:

They will lose a portion of their own profits;

Another competing RaaS could choose not to share profits with the Rollup framework and maintain long-term economic dominance.

Therefore, from a game theory perspective, for RaaS providers to survive, the rational decision is not to share profits with the underlying framework.

So, if RaaS providers don't share profits, how do Rollup frameworks accrue value?

If anyone can freely use an open-source framework to build a Rollup system, is it economically feasible to develop open-source Rollup frameworks?

The answer is not so simple. For a Rollup framework to be "economically feasible," it must generate sustainable long-term value. Idan Levin shared a good thinking model on how to achieve this. Let's expand on this model here. Rollup frameworks can accrue value in three main ways:

Indirect value accrual: If the framework is good, more and more teams will use it. This will attract developers and more attention to the ecosystem, helping the framework team further develop tools and create a positive reinforcement loop for the entire system.

Semi-direct value accrual: Some companies built on top of the framework may be incentivized to share revenue with the framework network. For example, Base currently has an agreement with OPStack to share part of the sorting fees with Optimism.

Why are they motivated to do this?

Because Base does not have the necessary developer ecosystem to keep up with the growth and development of the OP framework. Imagine if the OP framework completely changed one of its modules, they could choose not to provide developer support to Base to keep up with these changes.

In addition, being part of the "Superchain" also provides network effects, such as cross-Rollup composability, which could be useful for chains like Base (and this may require sharing revenue with Optimism).

Here's a key point to note: the incentive mechanisms for Rollup and Rollup frameworks may not always be consistent. At any time, Rollup can choose to go its own way, customize the framework, and abolish any revenue-sharing agreements.

Direct value accrual: Rollups built using the same framework (such as OPStack) (e.g., the Optimism mainnet) can have Gas as the native token (e.g., OP), and all MEV in the network will belong to the framework team. Additionally, the team can "extract" some additional direct value:

Establishing their own RaaS - the framework can choose to compete in the RaaS space and provide their own sequencer hosting and consulting services. If many frameworks start doing this, the RaaS business model will be difficult to sustain in the long run. This is because the framework can leverage its reputation and position in the market to compete with any external RaaS providers built on top of it.

Leveraging Rollup composability: Anyone can build a Rollup by using the framework as is or modifying it. However, to gain network effects and interoperability with other startups built on the same framework, the framework may need to comply with certain defined standards.

This is the chain rule of OPStack. To be part of the Superchain, certain rules must be followed. These rules are defined by the OP governance body. For example, one of these rules may be that all Rollups in the Superchain must use OP as the Gas token. This could also evolve to include MEV share rules, such as X% of cross-chain MEV income returning to the OP treasury.

The Superchain framework team can customize a "value capture" mechanism based on their goals and ambitions using the above three parts to gain any direct value. There are several options (not exhaustive) to achieve this:

Deploying their own Rollup;

Deploying their own RaaS;

Leveraging composability to manage framework standards.

Conclusion

The rapid development of Rollup frameworks and Rollup as a Service (RaaS) providers in the blockchain space has raised questions about their value accrual. While the execution layer captures most of the value, Rollup frameworks can indirectly accrue value through adoption and enhancement. Some Rollup frameworks may even share revenue, creating semi-direct value accrual. Additionally, by deploying their own Rollup and leveraging Rollup composability, frameworks can directly capture value. Finding the right balance between competition and cooperation as the ecosystem develops is crucial for the sustainable development of Rollup frameworks and RaaS providers.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。