Quantum Security Threats and Responses in Blockchain

On March 10, 2024, Vitalik Buterin, co-founder of Ethereum, published a new article titled "How to hard-fork to save most user's funds in a quantum emergency" on the Ethereum research forum (ethresear.ch) [1]. In the article, he stated that the quantum computing attack threat facing the Ethereum ecosystem can be mitigated by using recovery hard fork strategies and post-quantum cryptographic techniques to protect user funds.

So, what exactly are quantum security threats for blockchain?

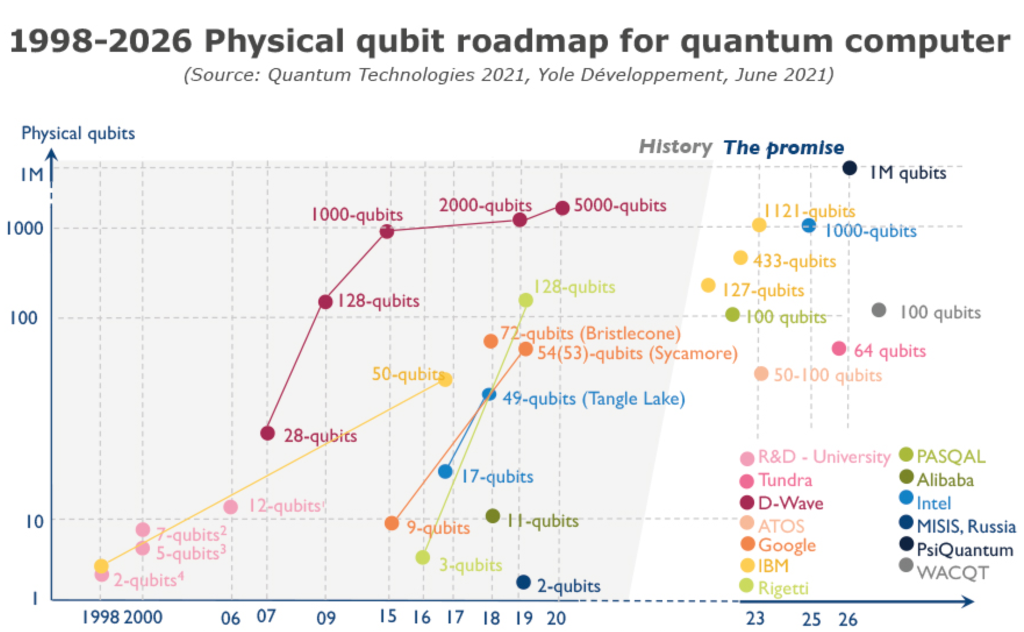

Quantum computing [2] is a new computing model that utilizes quantum mechanics to manipulate quantum information units for computation. It was proposed in the 1980s, and for the next decade, quantum computing remained in the abstract theoretical stage. It wasn't until the mid-1990s when two quantum algorithms, the Shor algorithm [3] (which solves large number factorization and discrete logarithm problems in polynomial time) and the Grover algorithm [4] (which provides quadratic speedup for exhaustive search problems on unstructured data), were introduced, that quantum computing moved beyond the abstract theoretical stage and entered a new phase of physical implementation, leading to what is now known as quantum computers. The following figure shows the development roadmap of physical quantum bits for quantum computers from 1998 to 2026:

Quantum computing is not omnipotent; it cannot solve all computational problems. Currently, it demonstrates its computational superiority in specific areas such as simulation (simulating processes occurring in nature, applicable to chemistry and bioengineering), cryptanalysis (breaking most traditional cryptographic systems, applicable to network security), and optimization (finding the optimal solution among feasible options, applicable to finance and supply chain).

The widespread application of blockchain is due to the new trust foundation it brings to collaboration among different parties, which is built on the security provided by underlying cryptography:

Trusted identity and transaction confirmation: Establishing user trusted identities based on asymmetric public-private key pairs and managing identity information uniformly. Digital signatures are used to confirm ownership of digital assets, and the holder of the valid signature key actually owns the assets.

Core consensus and operational security: Constructing consensus mechanisms based on modern cryptographic technologies such as hash functions, threshold signatures, and verifiable random functions to ensure the secure use of consensus mechanisms.

Privacy protection and secure sharing: Building privacy protection schemes based on rich functional cryptographic technologies such as zero-knowledge proofs, secure multiparty computation, and fully homomorphic encryption to achieve secure data sharing on the blockchain.

Controllable supervision and compliant applications: Integrating and deploying cryptographic technologies such as ring signatures, homomorphic encryption schemes, stealth addresses, and secret sharing to ensure the secure supervision of blockchain transactions.

The use of public key cryptography in the above involves roughly two aspects: the digital signature mechanism used to prevent tampering of on-chain transactions and the secure transmission protocol used for communication between nodes. Due to the influence of the Shor algorithm, the security of the aforementioned public key cryptography in use cannot be effectively guaranteed. When considering the time required for specialized cryptographic cracking by quantum computers and the time needed to store data on the blockchain and upgrade existing blockchain systems to a quantum-secure level, if the sum of the latter two exceeds the former, the data on the blockchain will be severely threatened by quantum computing.

Considering the rapid development of quantum computing and the continuous increase in computing power it brings, there are currently two main technological approaches to effectively address security risks:

A new mathematical problem-based post-quantum cryptography [5] technology route that does not rely on physical devices;

A quantum cryptography [6] technology route based on dedicated physical devices.

Taking into account various factors such as practical implementation and verification, to ensure the long-term security of blockchain evolution, it is advisable to consider deploying blockchain to a quantum-secure level in advance through post-quantum cryptography migration while maintaining compatibility with existing cryptographic security. Ideally, the existing public key cryptographic algorithms used in blockchain should be upgraded to post-quantum secure algorithms, which should strive to meet the following characteristics as much as possible:

Small key and short signature: Every transaction on the blockchain includes signature information, and the public key for verifying any transaction is also stored on the chain. If the key and signature size are too large, it will significantly increase the storage cost and communication overhead of the blockchain.

High computational efficiency: The number of transactions that can be processed during blockchain operation is largely related to the running time of the algorithm, especially the signature verification algorithm. Algorithms with faster computational efficiency can better support high-performance blockchain applications.

Current Status of Post-Quantum Cryptography Development

Post-quantum cryptography, in a nutshell, refers to the first generation of cryptographic algorithms that can resist attacks from quantum computers against existing cryptographic algorithms:

Targeting public key cryptographic systems;

Relying on new mathematical problems;

Not requiring dedicated device support;

Secure under both classical and quantum computing conditions.

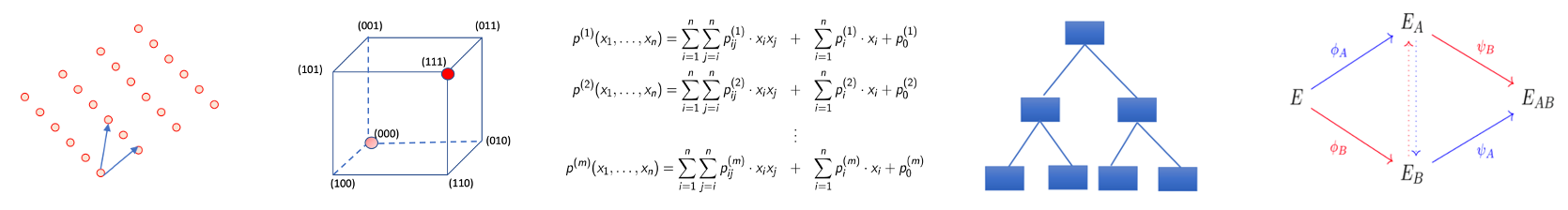

Currently, there are five mainstream construction technology routes, as shown in the following figure from left to right: lattice, code-based, multivariate, hash-based, and isogeny-based:

Lattice: Based on hard problems on lattices.

Code-based: Based on the difficulty of decoding.

Multivariate: Based on the intractability of multivariate quadratic polynomial systems over finite fields.

Hash-based: Based on the collision resistance of hash functions.

Isogeny-based: Based on pseudo-random walks on supersingular elliptic curves.

The establishment of new generation cryptographic algorithms will involve the establishment of standard cryptographic systems. The most noteworthy aspect of post-quantum cryptography standards is the post-quantum cryptography standardization project of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) [7], which has been in the final stages of standardization since its launch in 2016. Looking back at the nearly ten-year standardization timeline, NIST:

On July 5, 2022, officially announced four post-quantum cryptographic standard candidate algorithms [8]:

Public key encryption/key encapsulation: CRYSTALS-KYBER;

Digital signatures: CRYSTALS-Dilithium, FALCON, SPHINCS+;

Among these, CRYSTALS-KYBER, CRYSTALS-Dilithium, and FALCON are all lattice-based cryptographic algorithms, but their security foundations differ. KYBER is based on the module lattice's MLWE hard problem, Dilithium is based on the module lattice's MLWE and MSIS hard problems, and FALCON is based on the NTRU lattice's SIS hard problem. In addition, SPHINCS+ is a stateless hash-based signature algorithm.

On August 24, 2023, FIPS203, FIPS204, and FIPS205 standard drafts were formed for CRYSTALS-KYBER, CRYSTALS-Dilithium, and SPHINCS+, and the FALCON standard draft will also be announced in 2024 [9].

It is evident that the standard algorithms currently chosen by NIST are mostly based on lattice-based technology routes. However, NIST has not put all its eggs in one basket. They are actively seeking a variety of choices beyond lattice construction. Alongside the announcement of the four standard algorithms in 2022, they also initiated the fourth round of post-quantum cryptographic standard algorithm evaluation, which focuses on public key encryption/key encapsulation algorithms, and the selected algorithms do not rely on lattice construction. In addition, a new round of digital signature algorithm solicitation has been launched independently of the fourth round evaluation, aiming to enrich the combination of post-quantum signature algorithms. This round focuses more on new proposals for algorithm construction that are different from existing lattice-based structures and have small signature sizes and fast verification speeds.

In addition to NIST standards, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) standardized the eXtended Merkle Signature Scheme (XMSS) as RFC 8391 in 2018 and the Leighton-Micali Signature (LMS) as RFC 8554 in 2019, both of which were accepted by NIST.

Quantum Algorithms for Lattice Problems

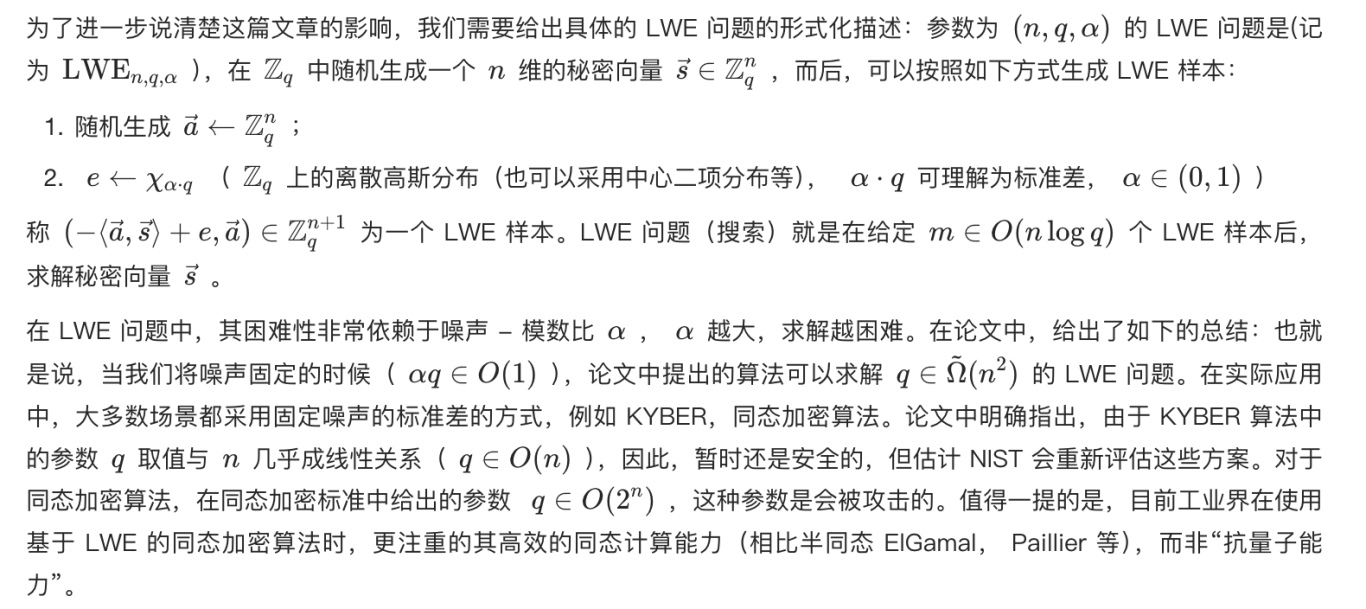

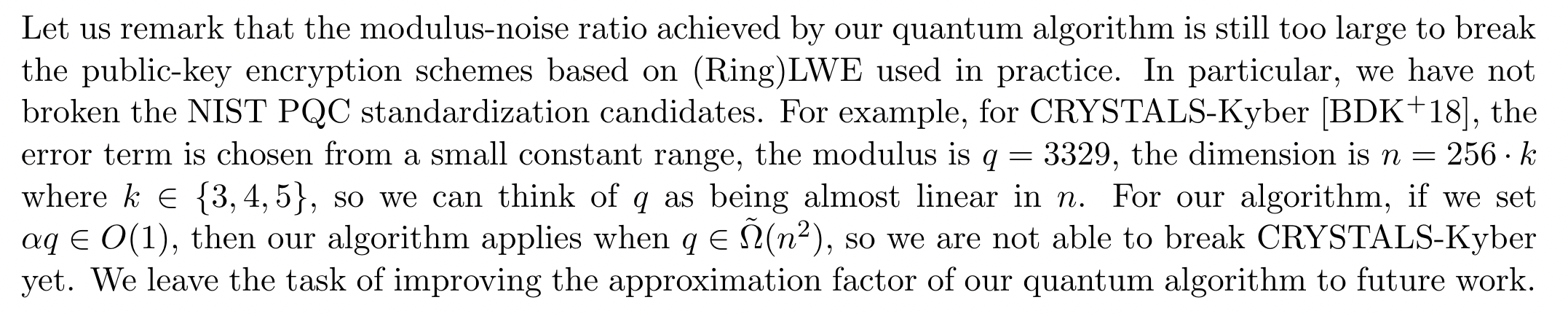

On April 10, 2024, an article titled "Quantum Algorithms for Lattice Problems" by Professor Yilei Chen on eprint caused a sensation in the academic community. The paper presents a quantum algorithm that can solve lattice-based hard problems in polynomial time, which has a significant impact on many cryptographic schemes based on lattice problems, potentially rendering them vulnerable to quantum computing attacks. For example, the widely used homomorphic encryption algorithm based on the LWE assumption. The correctness of the algorithm in the paper is currently unknown.

The difficulty of the LWE problem was rigorously demonstrated by Oded Regev in the paper "On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography." Specifically, the author reduced the difficulty of the LWE problem to the discrete Gaussian sampling problem on lattices, which can be easily reduced to classic problems such as GapSVP, SIVP, and others. This indicates that the LWE problem is even more difficult than these classic lattice problems. After the rigorous reduction of the difficulty of the LWE problem, a large number of cryptographic schemes based on LWE emerged, covering (homomorphic) encryption, signatures, key exchange, and advanced cryptographic primitives such as identity-based encryption and attribute-based encryption. Among these, the most widely used ones in the industry are mainly focused on fully homomorphic encryption and the post-quantum standard algorithms published by NIST (KYBER, Dilithium, etc.).

Summary

The publication of this paper has caused a great sensation in the academic community and has sparked discussions among many professionals. However, due to the extremely high level of difficulty in understanding the paper, it is likely that fewer than five scholars worldwide can fully comprehend its content, and it may take 1-2 years to fully verify the correctness of the paper. Currently, there are many discussions and analyses on various platforms such as forums, public accounts, and Zhihu, focusing on the potential impact if the algorithm in the paper is correct. However, no one can draw a conclusion on the correctness of the algorithm in the paper. Notably, renowned cryptographer N. P. Smart published a blog post titled "Implications of the Proposed Quantum Attack on LWE," detailing the impact of this attack and providing some viewpoints, summarized as follows:

This paper has not yet been peer-reviewed, and even if it is verified to be correct, it would still depend on quantum computers. Therefore, as long as quantum computers have not been realized, it will have no impact on the cryptographic schemes currently in use.

According to the results given in the paper, the previously standardized algorithms by NIST, such as Kyber and Dilithium, are still unbreakable. However, NIST may reconsider the parameters of these algorithms.

For commonly used RLWE homomorphic encryption algorithms such as BFV/CKKS/BGV, these algorithms fall within the attack capabilities presented in this paper. However, from both academic and industrial perspectives, the "homomorphic property" of homomorphic encryption technology is more attractive than its "quantum resistance." Few people would use RLWE homomorphic encryption algorithms for the sake of "quantum resistance," just as cryptographic schemes based on elliptic curves rely on the discrete logarithm problem, for which quantum algorithms have been proposed early on, but the academic and industrial communities are still researching and using these schemes.

Latest News: There are computational issues with Professor Chen's paper, and the lattice cryptography alert has been temporarily lifted.

[1] https://ethresear.ch/t/how-to-hard-fork-to-save-most-users-funds-in-a-quantum-emergency/18901/9

[2] Benioff P. The computer as a physical system: A microscopic quantum mechanical Hamiltonian model of computers as represented by Turing machines[J]. Journal of statistical physics, 1980, 22: 563-591.

[3] Shor P W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring[C]//Proceedings 35th annual symposium on foundations of computer science. Ieee, 1994: 124-134.

[4] Grover L K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search[C]//Proceedings of the twenty-eighth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. 1996: 212-219.

[5] Bernstein, D.J. (2009). Introduction to post-quantum cryptography. In: Bernstein, D.J., Buchmann, J., Dahmen, E. (eds) Post-Quantum Cryptography. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

[6] Gisin N, Ribordy G, Tittel W, et al. Quantum cryptography[J]. Reviews of modern physics, 2002, 74(1): 145.

[7]https://csrc.nist.gov/Projects/post-quantum-cryptography/post-quantum-cryptography-standardization

[8]https://csrc.nist.gov/News/2022/pqc-candidates-to-be-standardized-and-round-4

[9]https://csrc.nist.gov/News/2023/three-draft-fips-for-post-quantum-cryptography

[10] Huelsing, A., Butin, D., Gazdag, S., Rijneveld, J., and A. Mohaisen, "XMSS: eXtended Merkle Signature Scheme", RFC 8391, DOI 10.17487/RFC8391, May 2018, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8391.

[11] McGrew, D., Curcio, M., and S. Fluhrer, "Leighton-Micali Hash-Based Signatures", RFC 8554, DOI 10.17487/RFC8554, April 2019, https://www.rfc-editor.org/info/rfc8554.

[12] Chen Y. Quantum Algorithms for Lattice Problems[J]. Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2024.

[13] Regev O. On lattices, learning with errors, random linear codes, and cryptography[J]. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 2009, 56(6): 1-40.

[14]https://nigelsmart.github.io/LWE.html

This article was co-authored by Dongni and Jiaxing from the ZAN Team (X account @zan_team).

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。