Once things that were on the fringes are now at the forefront of the new financial revolution and are about to gain official regulatory recognition.

Author: Leviathan News

Translation: Deep Tide TechFlow

Hello, SQUIDs! Today we will analyze two stablecoin bills in the U.S. Congress.

The final stablecoin bill is expected to pass later in 2025, so it is crucial to understand the content of the bills and how they will impact our industry.

Introduction

We are in a bull market, a bull market for stablecoins.

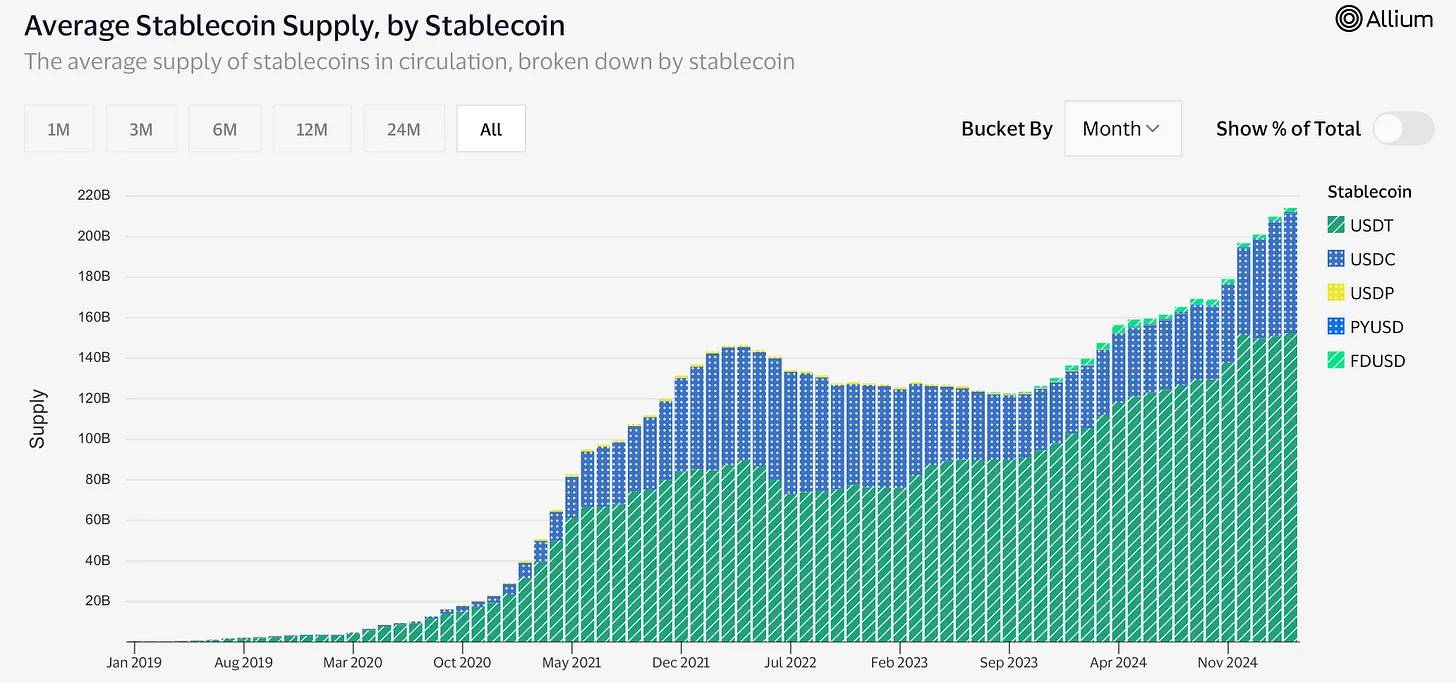

Since the market bottomed out after the FTX collapse, the supply of stablecoins has doubled in 18 months, reaching $215 billion. This does not include emerging cryptocurrency-exclusive participants like Ondo, Usual, Frax, and Maker.

With current interest rates at 4%-5%, the stablecoin industry is highly profitable. Tether reported a profit of $14 billion last year with fewer than 50 employees! Circle plans to apply for an IPO in 2025. Everything revolves around stablecoins.

With Biden leaving office, we can almost be certain that stablecoin legislation will arrive in 2025. Banks have watched Tether and Circle seize market opportunities for five years. Once the new laws are passed and stabilize stablecoins, every bank in the U.S. will issue its own digital dollar.

Currently, there are two main legislative proposals moving forward: the Senate's "Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act" (GENIUS Act) and the House's "Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act" (STABLE Act).

These bills have been discussed repeatedly in the legislative process for a long time… but now a consensus has finally been reached, and one of them will pass this year.

The common goal of the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act is to create a federal licensing system for issuers of "payment stablecoins," establish strict reserve requirements, and clarify regulatory responsibilities.

Payment stablecoins are just a catchy term referring to digital dollars issued by banks or non-bank institutions authorized based on their balance sheets. They are defined as digital assets used for payments or settlements, pegged to a fixed currency value (usually pegged 1:1 to the dollar), and backed by short-term government bonds or cash.

Critics of stablecoins argue that this will undermine the government's ability to control monetary policy. To understand their concerns, you can read the classic article "Taming Wildcat Stablecoins" by Gorton and Zhang.

The primary rule of modern dollars is: they must never be unpegged.

Wherever you are, one dollar is one dollar.

Deposited in JP Morgan, held in Venmo or PayPal, or even in virtual credits in Roblox, wherever dollars are used, they must always adhere to the following two rules:

Every dollar must be interchangeable: Dollars cannot be psychologically categorized, labeled as "special," "reserved," or tied to specific uses. Dollars in JP Morgan cannot be considered different from those on Tesla's balance sheet.

Dollars are fungible: Everywhere, all dollars are "the same"—cash, bank deposits, reserves are all alike.

The entire legal financial system is built around this principle.

This is also the Federal Reserve's entire responsibility—to ensure that the dollar remains pegged and operates strongly. It must never be unpegged.

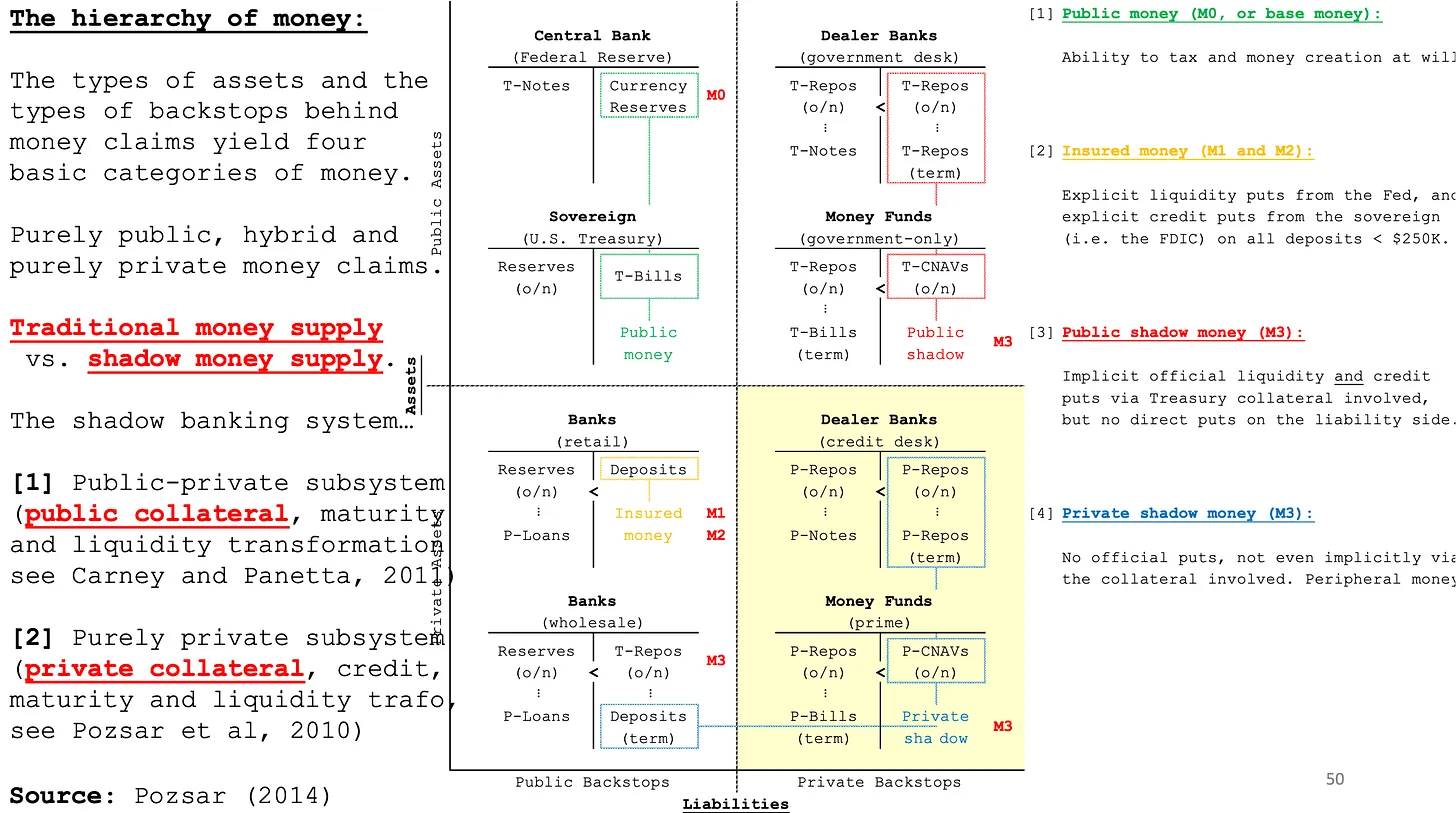

The slide above is from Zoltan Pozsar's "How the Financial System Works." It is an authoritative guide on the dollar that can provide you with a wealth of background information to help understand the goals these stablecoin bills are trying to achieve.

Currently, all stablecoins are classified in the lower right corner as "Private Shadow Money." If Tether or Circle were to be shut down or go bankrupt, it could be catastrophic for the crypto industry, but the overall impact on the financial system would be minimal. Life would go on as usual.

Economists are concerned that once stablecoins are legalized, allowing banks to issue them and turning them into "Public Shadow Money," the risks will truly emerge.

Because, in the legal currency system, the only important question is: who will be bailed out when a crisis occurs? This is the core of what the slide above illustrates.

Remember 2008? At that time, mortgage-backed securities (MBS) accounted for a very small proportion of the global economy, but banks always operated with nearly 100 times leverage, and collateral flowed across the balance sheets of various banks. Therefore, when one bank (Lehman Brothers) collapsed, the leverage and interconnectedness of the balance sheets triggered a series of similar explosive failures.

The U.S. Federal Reserve and other monetary institutions like the European Central Bank (ECB) had to intervene (globally) to ensure that all banks' balance sheets were shielded from these "toxic debts." Although it cost billions in bailout funds, the banks were saved. The Federal Reserve will always bail out banks because without banks, the global financial system cannot operate, and the dollar could become unpegged in those poorly managed institutions.

In fact, you don't even need to go back to 2008 to see similar examples.

In March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank collapsed rapidly over a weekend due to a bank run triggered by digital withdrawals and panic on social media. The failure of Silicon Valley Bank was not due to high-risk mortgage loans, derivatives, or cryptocurrencies, but because it held supposedly "safe" long-term U.S. Treasury bonds, which significantly lost value as interest rates rose. However, despite Silicon Valley Bank's relatively small size in the banking system, its collapse still threatened systemic contagion, forcing the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury to intervene quickly to ensure all deposits were safe—even those exceeding the $250,000 standard insurance limit. This rapid government intervention highlighted a principle: when dollars become untrustworthy anywhere, the entire financial system could collapse overnight.

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank immediately had a ripple effect on the crypto market. Circle, the issuer of USDC, held about $30 billion in total supply at the time, a significant portion of which was stored in Silicon Valley Bank. Over that weekend, USDC depegged by about 8 cents, briefly trading as low as $0.92, triggering panic in the crypto market. Now, imagine what would happen if such a depegging phenomenon occurred globally? This is precisely the risk that these new stablecoin bills face. By allowing banks to issue their own stablecoins, policymakers may embed potential instability tools deeper into the global financial infrastructure, significantly increasing risks when the next financial shock occurs (not "if," but "when").

The core point of Zoltan Pozsar's slides is that when financial disasters occur, it ultimately falls to the government to rescue the financial system.

Today, we have multiple categories of dollars, each with different levels of safety.

Dollars directly issued by the government (i.e., M0 dollars) enjoy the full credit guarantee of the U.S. government and are essentially risk-free. However, as funds enter the banking system and are classified as M1, M2, and M3, the government's guarantee gradually weakens.

This is precisely why bank bailouts are so controversial.

Bank credit is at the core of the U.S. financial system, but banks often have incentives to pursue maximum risk within the legal limits, often leading to dangerous over-leveraging. When this risky behavior crosses the line, financial crises erupt, and the Fed must intervene and provide bailouts to prevent systemic collapse.

The concern is that today, the vast majority of money exists in the form of bank-issued credit, and there is deep interconnectedness and leverage among banks. If multiple banks were to fail simultaneously, it could trigger a domino effect, spreading losses across every industry and asset class.

In 2008, we witnessed this situation occur in reality.

Few would think that a seemingly isolated sector of the U.S. housing market could shake the global economy, but due to extreme leverage and fragile balance sheets, once what was once considered safe collateral collapsed, banks could not withstand the shock.

This context helps explain why there has been significant disagreement and slow progress on stablecoin legislation.

As a result, lawmakers have taken a cautious approach, carefully defining what constitutes a stablecoin and who is eligible to issue stablecoins.

This cautious approach has led to the emergence of two competing legislative proposals: the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act. The former takes a more flexible approach to stablecoin issuance, while the latter imposes strict restrictions on issuance qualifications, interest payments, and issuer qualifications.

However, both bills represent a crucial step forward and could unlock trillions of dollars in potential for on-chain transactions.

Next, let’s analyze these two bills in detail, understanding their similarities, differences, and the potential impacts they may have.

GENIUS Act: The Senate's Stablecoin Framework

The 2025 GENIUS Act (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoins Act) was introduced by Senator Bill Hagerty (Republican, Tennessee) in February 2025 and has received bipartisan support, including participation from Senators Tim Scott, Kirsten Gillibrand, and Cynthia Lummis.

On March 13, 2025, the bill passed the Senate Banking Committee with a vote of 18 in favor and 6 against, becoming the first cryptocurrency-related bill to pass through that committee.

According to the GENIUS Act, stablecoins are explicitly defined as digital assets pegged to a fixed currency value, typically at a 1:1 ratio with the U.S. dollar, primarily used for payment or settlement purposes.

While there are other types of "stablecoins," such as Paxos' PAXG (pegged to gold), under the current GENIUS Act, tokens pegged to commodities like gold or oil are generally not within its regulatory scope. Currently, the bill only applies to fiat-backed stablecoins.

Commodity-backed tokens are typically regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) or the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), depending on their structure and use, rather than being bound by specific stablecoin legislation.

If in the future Bitcoin or gold becomes the dominant payment currency, and we all migrate to Bitcoin-supported fortresses, then the bill may apply, but for now, they are still not directly regulated under the GENIUS Act.

This is a Republican-led bill, introduced because the Biden administration and Democrats in the previous government refused to draft any cryptocurrency-related legislation.

The bill introduces a federal licensing system, stipulating that only authorized entities can issue payment stablecoins, and establishes three categories of licensed issuers:

Bank Subsidiaries: Stablecoins issued by subsidiaries of insured depository institutions (e.g., bank holding companies).

Non-Insured Depository Institutions: Including trust companies or other state-chartered financial institutions that accept deposits but are not insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (the current status of many stablecoin issuers).

Non-Bank Entities: A new federally chartered category for non-bank stablecoin issuers (sometimes referred to in the bill as "payment stablecoin issuers"), which will be chartered and regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).

As you might guess, all issuers must fully back their stablecoins 1:1 with high-quality liquid assets (including cash, bank deposits, or short-term U.S. Treasury securities). Additionally, these issuers are required to undergo regular public disclosures and audits by registered accounting firms to ensure transparency.

A highlight of the GENIUS Act is its dual regulatory structure. It allows smaller issuers (those that have not issued more than $10 billion in stablecoins) to operate under state regulation, provided that the regulatory standards of their state meet or exceed federal guidelines.

Wyoming is the first state to explore issuing its own stablecoin governed by local laws.

Larger issuers, on the other hand, must operate under direct federal regulation, primarily overseen by the OCC or the appropriate federal banking regulators.

Notably, the GENIUS Act explicitly states that compliant stablecoins are neither securities nor commodities, thereby clarifying regulatory jurisdiction and alleviating concerns about potential SEC or CFTC oversight.

In the past, critics have called for stablecoins to be regulated as securities. By this classification, stablecoins can be distributed more broadly and conveniently.

STABLE Act: House Rules

Introduced by Representatives Bryan Steil (Republican, Wisconsin) and French Hill (Republican, Arkansas) in March 2025, the Stablecoin Transparency and Accountability for a Better Ledger Economy Act (STABLE Act) is very similar to the GENIUS Act but introduces unique measures to mitigate financial risks.

The most notable point is that the bill explicitly prohibits stablecoin issuers from providing interest or returns to holders, ensuring that stablecoins strictly serve as cash-equivalent payment tools rather than investment products.

Additionally, the STABLE Act imposes a two-year moratorium on the issuance of new algorithmic stablecoins. These stablecoins rely solely on digital assets or algorithms to maintain their pegged value, and this move aims to await further regulatory analysis and protective measures.

Two Bills, Shared Legal Foundations

Despite some differences, the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act reflect a broad bipartisan consensus on the foundational principles of stablecoin regulation. The two bills agree on the following aspects:

Strict requirements for stablecoin issuers to obtain licenses to ensure regulatory oversight.

Requirements for stablecoins to maintain full 1:1 backing with high-quality, safe reserve assets to mitigate bankruptcy risks.

Implementation of strong transparency requirements, including regular public disclosures and independent audits.

Establishment of clear consumer protection measures, such as asset segregation and priority claims in the event of issuer bankruptcy.

Providing regulatory clarity by explicitly classifying stablecoins as non-securities or commodities, thereby simplifying jurisdictional and regulatory processes.

Despite sharing foundational principles, the GENIUS Act and the STABLE Act diverge on three key points:

- Interest Payments:

The GENIUS Act allows stablecoins to pay interest or returns to holders, thereby opening the door for innovation in the financial sector and broader application scenarios. In contrast, the STABLE Act strictly prohibits interest payments, explicitly limiting stablecoins to pure payment tools and excluding their function as investment or yield-bearing assets.

- Algorithmic Stablecoins:

The GENIUS Act takes a cautious but lenient approach, requiring regulators to closely study and monitor such stablecoins rather than imposing an immediate blanket ban. In contrast, the STABLE Act adopts a clear and direct two-year moratorium on the issuance of new algorithmic stablecoins, reflecting a more cautious stance after past market collapses.

- State vs. Federal Regulatory Thresholds:

The GENIUS Act explicitly states that when an issuer's total stablecoin issuance reaches $10 billion, it must transition from state regulation to federal regulation, clearly defining when a stablecoin issuer has systemic importance. The STABLE Act implicitly supports a similar threshold but does not specify a concrete figure, granting regulators more discretion to make ongoing adjustments based on market developments.

Why Prohibit Interest? Analyzing the Stablecoin Yield Ban

A notable provision in the House STABLE Act (and some earlier proposals) is the prohibition on stablecoin issuers paying interest or any form of yield to token holders.

In practice, this means that compliant payment stablecoins must operate like digital cash or stored-value instruments—if you hold one stablecoin, it is always redeemable for one dollar, but over time, it will not yield any additional returns.

This stands in stark contrast to other financial products, such as bank deposits that may earn interest or money market funds that accumulate returns.

So, why impose such a restriction?

The rationale behind this "interest prohibition rule" has multiple legal and regulatory reasons, primarily based on U.S. securities law, banking law, and related regulatory guidelines.

Avoiding Classification as Securities (Howey Test)

One major reason for prohibiting interest payments is to avoid stablecoins being classified as investment securities under the Howey test.

The Howey test originates from a 1946 U.S. Supreme Court case. According to this test, if an asset meets the following conditions, it is considered an "investment contract" (and thus a security): there is an investment of money in a common enterprise, and the investor expects to profit from the efforts of others. However, stablecoins, strictly functioning as payment tokens, are not intended to provide "profits"; they are merely a stable-value one-dollar token.

However, once an issuer begins to offer returns (for example, if a stablecoin pays a 4% annual yield through its reserves), users will expect to profit from the issuer's efforts (the issuer may generate returns by investing the reserves). This could trigger the Howey test, leading to the risk of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) claiming that the stablecoin is a security offering.

In fact, former SEC Chairman Gary Gensler has suggested that some stablecoins may fall under securities, especially if they resemble shares of money market funds or have profit characteristics. To mitigate this risk, the drafters of the STABLE Act explicitly prohibit paying any form of interest or dividends to token holders, ensuring there is no "profit expectation." This way, stablecoins can maintain their attributes as practical payment tools rather than investment contracts. Through this approach, Congress can confidently classify regulated stablecoins as non-securities, which is a shared position of both bills.

However, the issue with this ban is that there are already interest-bearing stablecoins on-chain, such as Sky's sUSDS or Frax's sfrxUSD. Prohibiting interest only adds unnecessary barriers for stablecoin companies looking to explore different business models and systems.

Maintaining the Boundary Between Banking and Non-Banking Activities (Banking Law)

U.S. banking law traditionally assigns the activity of accepting deposits as the exclusive domain of banks (and savings institutions/credit unions). (Deposits are essentially securities.) The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 (BHCA) and related regulations prohibit commercial companies from accepting deposits from the public—if you accept deposits, you typically need to become a regulated bank; otherwise, you may be deemed a bank, triggering a series of regulatory requirements.

When customers entrust you with funds, and you promise to return those funds and pay interest, this is effectively a deposit or investment note.

Regulators have indicated that stablecoins that closely resemble banking deposit functions may touch these legal boundaries.

By prohibiting interest payments, the drafters of the STABLE Act aim to ensure that stablecoins do not appear to be tools masquerading as uninsured bank accounts. Instead, stablecoins are more akin to stored-value cards or prepaid balances, which non-bank entities are allowed to issue under specific regulations.

As one legal scholar noted, companies should not be able to "evade compliance with the Federal Deposit Insurance Act and the Bank Holding Company Act" simply by being packaged as stablecoins due to their deposit-accepting behavior.

In fact, if stablecoin issuers were allowed to pay interest to holders, they might compete with banks for similar deposit-like funds (but without the regulatory safeguards that banks have, such as FDIC insurance or Federal Reserve oversight), which is clearly something that banking regulators would find difficult to accept.

It is also important to note that the U.S. dollar and financial system rely entirely on banks being able to issue loans, mortgages, and other forms of debt (for housing, commercial purposes, and other goods and trade), which typically have very high leverage and are supported by retail bank deposits as reserve requirements.

JP Koning's analysis of PayPal dollars is quite enlightening here. Currently, PayPal actually offers two forms of dollars.

One is the traditional PayPal balance we are familiar with—these dollars are stored in a traditional centralized database. The other is the newer, crypto-based dollar, known as PayPal USD, which exists on the blockchain.

You might think the traditional version is safer, but surprisingly, PayPal's crypto dollars are actually safer and provide stronger consumer protection.

The reason is as follows: PayPal's traditional dollars are not necessarily backed by the safest assets.

If you look closely at their disclosures, you'll find that PayPal invests only about 30% of customer balances in top-tier assets like cash or U.S. Treasury securities. The remaining nearly 70% is invested in riskier, longer-term assets such as corporate debt and commercial paper.

Even more concerning is that, from a strict legal standpoint, these traditional balances do not actually belong to you.

If PayPal were to go bankrupt, you would become an unsecured creditor, competing with others owed money by PayPal, and there is no guarantee you would get your balance back in full.

In contrast, PayPal USD (the crypto version) must be 100% backed by ultra-safe short-term assets (such as cash equivalents and U.S. Treasury securities), as required by the New York State Department of Financial Services.

Not only are the supporting assets safer, but these crypto balances explicitly belong to you: the reserves backing these stablecoins must be legally established for the benefit of the holders. This means that if PayPal goes bankrupt, you will have priority over other creditors in reclaiming your funds. This distinction is particularly important, especially when considering broader financial stability. Stablecoins like PayPal USD are not affected by the balance sheet risks, leverage, or collateral issues of the wider banking system.

During a financial crisis—precisely when you need safety the most—investors may flock to stablecoins precisely because they are not entangled with the high-risk lending practices or instability of fractional reserves associated with banks. Ironically, stablecoins may ultimately function more as a safe haven tool rather than the high-risk speculative instruments many perceive them to be.

This poses a significant problem for the banking system. In 2025, the speed of capital movement is as fast as the internet. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was precisely due to panicked investors rapidly making digital withdrawals, exacerbating its problems and ultimately leading to its complete failure.

Stablecoins are essentially a higher-quality form of currency, which banks are extremely fearful of.

The compromise in these bills is to allow non-bank companies to issue dollar tokens, provided they do not cross into the realm of paying interest—thereby avoiding direct encroachment on the territory of banks that offer interest-bearing accounts.

This boundary is very clear: banks accept deposits and lend them out (which can pay interest), while under this bill, stablecoin issuers must merely hold reserves and facilitate payments (not lend, not pay interest).

This is essentially a modern interpretation of the "narrow banking" concept, where stablecoin issuers act almost like a 100% reserve institution, not engaging in maturity transformation or providing yields.

Historical Analogy (Glass-Steagall Act and Regulation Q)

Interestingly, the view that currency used for payments should not pay interest has a long history in U.S. regulatory history.

The Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 is famous for separating commercial banks from investment banks, but it also introduced Regulation Q, which prohibited banks from paying interest on demand deposit accounts (i.e., checking accounts) for decades. The rationale at the time was to prevent unhealthy competition among banks for deposits and to ensure the stability of banks (excessive interest incentives in the 1920s led to risk-taking behavior, which contributed to bank failures).

Although the ban of Regulation Q was eventually phased out (fully repealed in 2011), its core principle remains: your liquid transaction balance should not simultaneously serve as an investment tool that earns interest.

Stablecoins are designed to be highly liquid transaction balances—akin to checking account balances or cash equivalents in wallets in the cryptocurrency space. By prohibiting interest payments on stablecoins, lawmakers are effectively echoing this ancient idea: to keep payment tools safe and simple, and to separate them from yield-bearing investment products.

This also avoids the potential emergence of uninsured shadow banking forms. (See Pozsar's views, remembering that private shadow banks cannot receive bailouts.)

If stablecoin issuers provide interest, they effectively operate like banks (accepting funds and investing them in Treasuries or loans to generate interest).

But unlike banks, their lending or investment activities would not be regulated beyond reserve rules, and users might perceive them as safe as bank deposits without realizing the associated risks.

Regulators are concerned that this could trigger a "bank run" risk during a crisis—if people believe stablecoins are as good as bank accounts, and they start to have problems, they may rush to redeem them, potentially triggering broader market pressures.

Thus, the no-interest rule forces stablecoin issuers to hold reserves but prohibits them from engaging in any lending or chasing yields through risky behavior, significantly reducing the risk of runs (since reserves are always equal to liabilities).

This delineation protects the stability of the financial system by preventing large-scale flows of funds into unregulated quasi-bank instruments.

Effectiveness, Practicality, and Impact

The direct result of this bill is to bring stablecoins fully under regulatory oversight, making them safer and more transparent.

Currently, stablecoin issuers like Circle (USDC) and Paxos (PayPal USD) voluntarily comply with strict state-level regulations, particularly New York's trust framework, but there is no unified federal standard yet.

These new laws will establish a uniform national standard, providing consumers with greater protection and ensuring that every dollar of stablecoin is truly backed 1:1 by high-quality assets (such as cash or short-term Treasuries).

This is a significant victory: it solidifies trust, making stablecoins safer and more credible, especially after experiencing major events like the collapse of UST and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

Moreover, by clarifying that compliant stablecoins are not securities, it eliminates the ongoing threat of unexpected SEC crackdowns, shifting regulatory authority to more appropriate financial stability regulators.

In terms of innovation, these bills are surprisingly forward-looking.

Unlike earlier strict proposals (such as the initial STABLE draft in 2020, which only allowed banks to issue), these new bills provide pathways for fintech companies and even large tech companies to issue stablecoins by obtaining federal licenses or partnering with banks.

Imagine companies like Amazon, Walmart, or even Google launching branded stablecoins and widely accepting them on their vast platforms.

In 2021, Facebook was already ahead of its time with its attempt to launch Libra. In the future, every company may have its own branded dollar. Even influencers and other private individuals might launch their own stablecoins…

Would you buy them? For example, "ElonBucks"? Or "Trumpbucks"?

We are ready.

However, these bills are not without their trade-offs.

No one can foresee how the future of decentralized stablecoins will unfold. It is certain that they will struggle to meet capital reserve requirements, licensing fees, ongoing audits, and other compliance costs. This could inadvertently favor industry giants like Circle and Paxos while squeezing smaller or decentralized innovators.

So, what will happen to DAI? If they cannot obtain a license, they may have to exit the U.S. market. The same situation applies to Ondo, Frax, and Usual. Currently, they do not meet the regulatory requirements under the existing status. Later this year, we may witness a significant industry shake-up.

Conclusion

The U.S. efforts to push stablecoin legislation demonstrate the tremendous progress in discussions related to this topic in just a few years.

What was once on the fringes is now at the forefront of a new financial revolution and is about to gain official regulatory recognition, albeit with strict conditions attached.

We have made significant strides, and these bills will unleash a wave of new stablecoin issuances.

The GENIUS Act slightly leans towards allowing market innovation within a regulatory framework (such as paying interest or new technologies), while the STABLE Act takes a more cautious approach in these areas.

As the legislative process moves forward, these differences will need to be reconciled. However, given the bipartisan support for the issue and the Trump administration's public desire to pass a bill by the end of 2025, we can foresee that one of these bills will become a reality.

This is undoubtedly a huge victory for our industry and the dollar.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。