编译:深潮TechFlow

零和注意力游戏

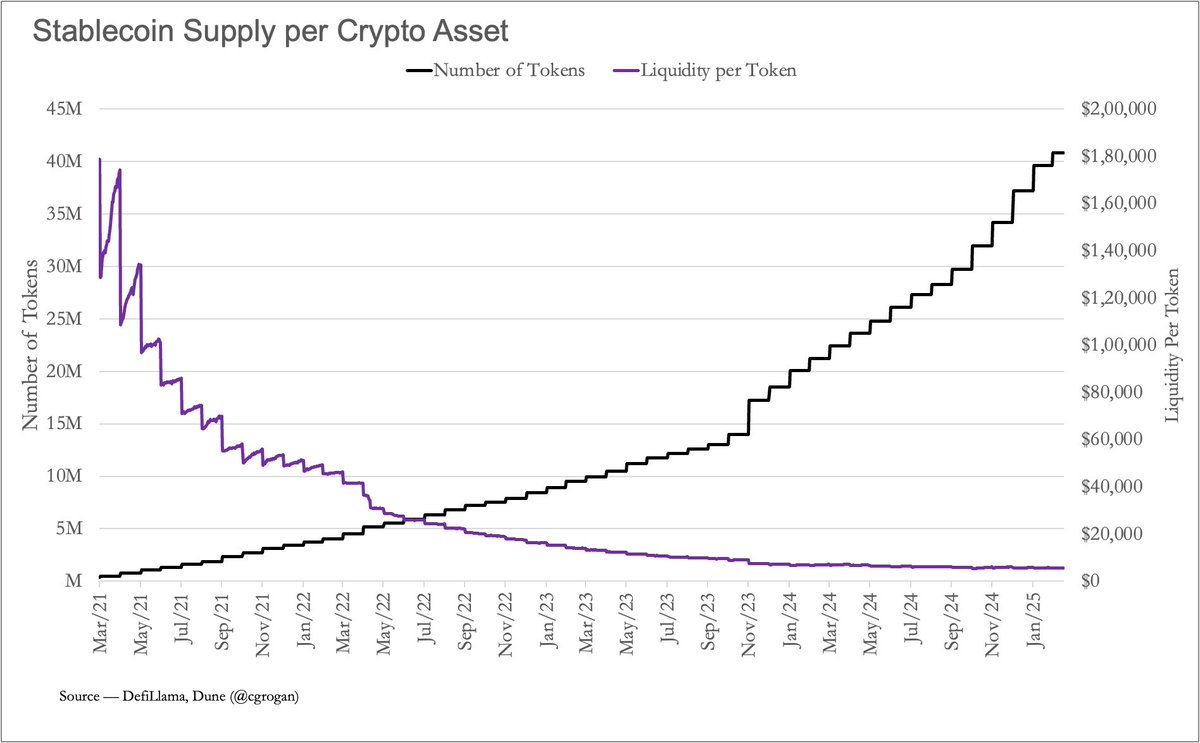

2021年,每种加密资产平均拥有约180万美元的稳定币流动性。然而,到2025年3月,这一数字已骤降至仅5500美元。

这张图表直观地展示了平均值的下降,同时也反映了当今加密领域中注意力零和博弈的本质。尽管代币的数量已激增至超过4000万种资产,但稳定币流动性(作为资本的粗略衡量标准)却停滞不前。其结果是残酷的——每个项目分得的资本减少,社区变得更加薄弱,用户参与度迅速衰退。

在这样的环境中,短暂的注意力不再是增长的渠道,而是一种负担。如果没有现金流的支撑,这种注意力会迅速转移,毫不留情。

收入是发展的锚点

大多数项目仍然以2021年的方式构建社区:创建一个Discord频道,提供空投激励,并希望用户能喊着“GM”(Good Morning)足够久以产生兴趣。但一旦空投结束,用户便迅速离开。这种情况并不意外,因为他们没有留下的理由。这时,现金流的作用便凸显出来——它不仅是一个财务指标,更是项目相关性的重要证明。能够产生收入的产品意味着存在需求。需求支撑估值,而估值反过来赋予代币引力。

尽管收入可能并非每个项目的最终目标,但如果没有收入,大多数代币根本无法存活足够长的时间以成为基础性资产。

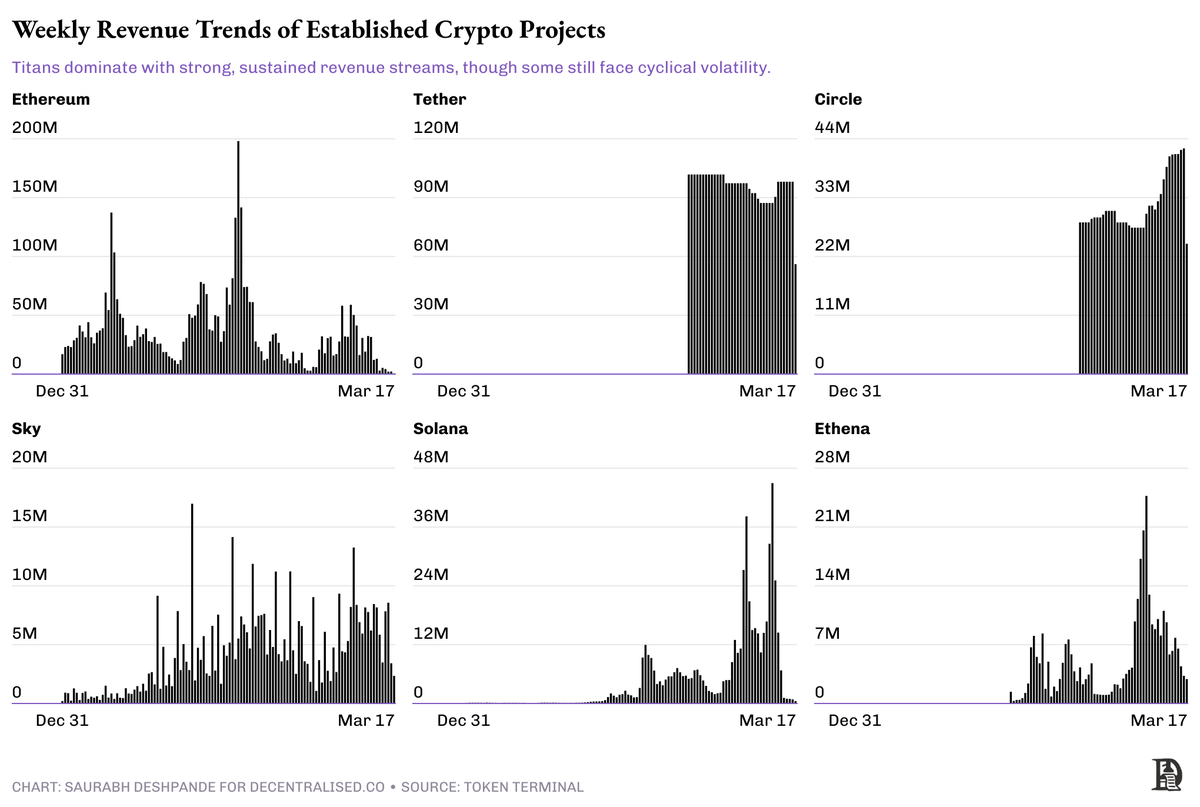

需要注意的是,一些项目的定位与行业其他部分截然不同。以以太坊(Ethereum)为例,它并不需要额外的收入,因为它已经拥有一个成熟且粘性的生态系统。验证者的奖励来自每年约2.8%的通胀,但由于EIP-1559的手续费销毁机制,这种通胀可以被抵消。只要销毁和收益能够平衡,ETH持有者就能避免稀释的风险。

但对于新项目来说,他们没有这样的奢侈条件。当只有20%的代币在流通中,而你仍在努力寻找产品与市场的契合点时,你实际上就像一家初创公司。你需要盈利,并证明自己具备持续盈利的能力,才能生存下去。

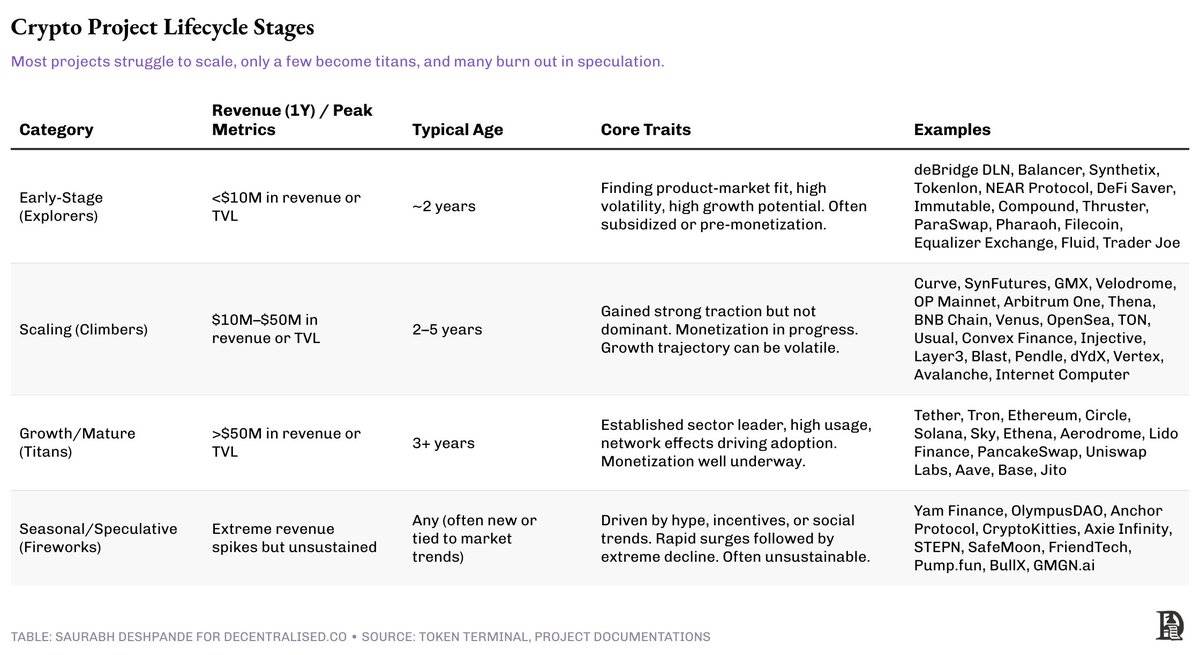

协议的生命周期:从探索者到巨头

与传统公司类似,加密项目也处于不同的成熟阶段。在每个阶段,项目与收入之间的关系——以及是选择再投资还是分配收入——都会发生显著变化。

探索者:优先求生

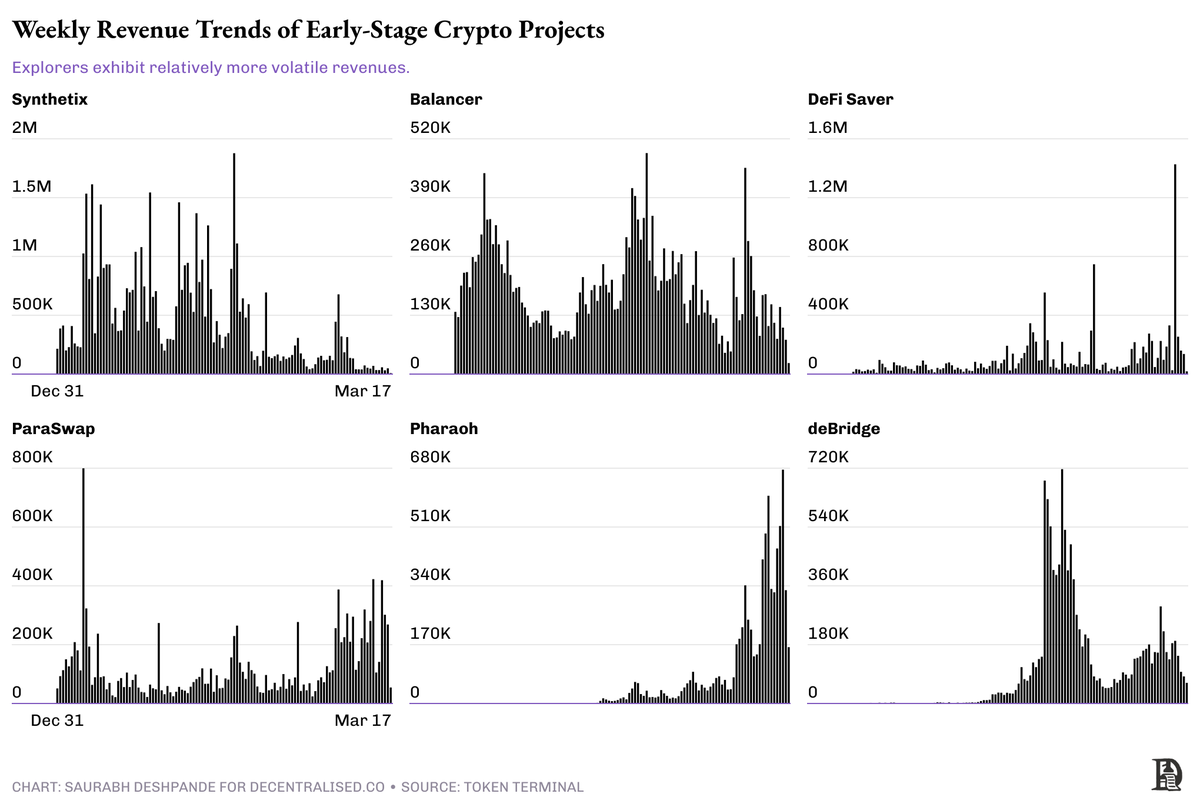

这些是处于早期阶段的项目,通常拥有中心化治理、脆弱的生态系统,并更注重实验而非盈利化。即使有收入,也往往是波动且不可持续的,更多反映市场投机行为而非用户忠诚度。许多项目依赖激励措施、补助金或风险投资来维持生存。

例如,像 Synthetix 和 Balancer 这样的项目已经存在了大约5年。它们的每周收入在10万美元到100万美元之间,活动高峰期会出现一些异常的激增。这种剧烈的波动和回落是这个阶段的典型特征,这并不是失败的迹象,而是波动性的体现。关键在于,这些团队能否将实验转化为可靠的使用场景。

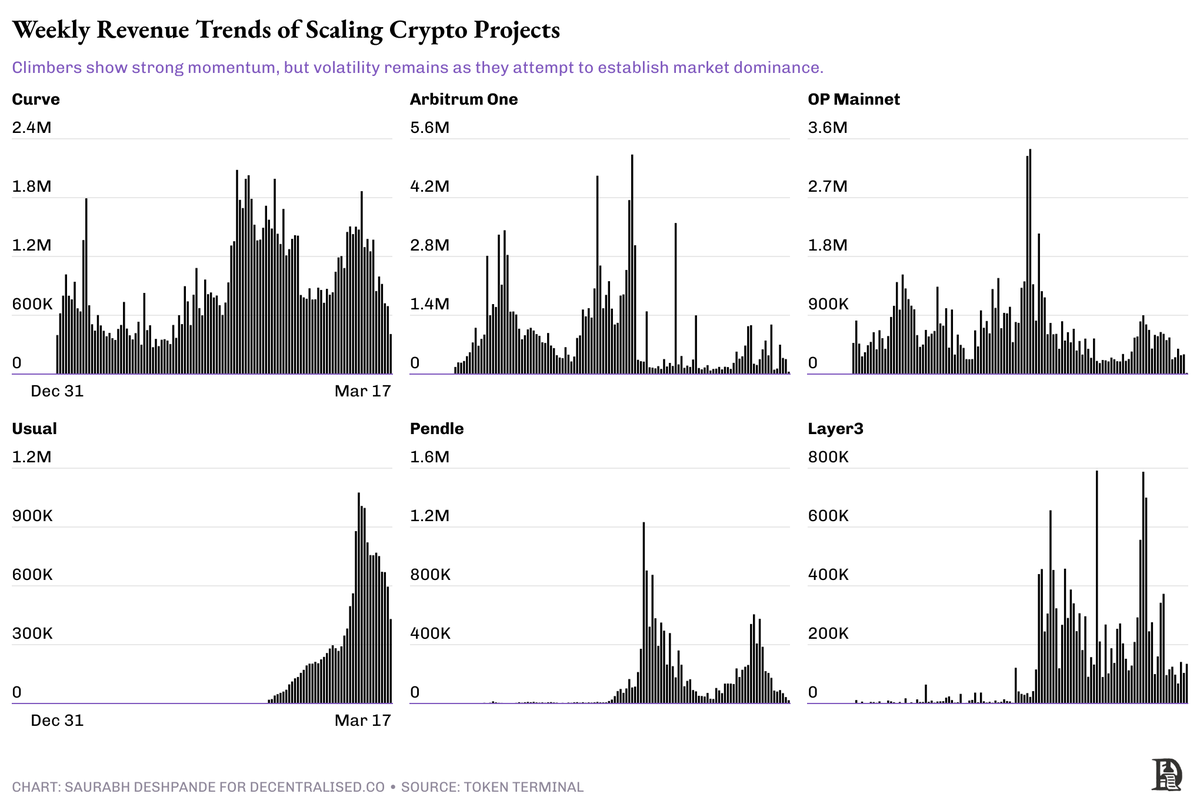

攀登者:有牵引力但仍不稳定

攀登者是进阶阶段的项目,年收入在1000万到5000万美元之间,逐渐摆脱了依赖代币发行的增长模式。它们的治理结构正趋于成熟,关注点也从单纯的用户获取转向长期用户留存。与探索者不同,攀登者的收入已能在不同周期中证明需求的存在,而不仅仅是由一次性炒作驱动。同时,它们正在进行结构性演变——从中心化团队向社区驱动的治理转型,并多样化收入来源。

攀登者的独特之处在于其灵活性。它们积累了足够的信任,可以尝试分配收入——有些项目开始进行收入分成或回购计划。但与此同时,它们也面临失去发展势头的风险,尤其是在过度扩张或未能加深护城河时。与探索者的首要任务是生存不同,攀登者必须做出战略权衡:是选择增长还是巩固?是分配收入还是再投资?是专注核心业务还是分散布局?

这一阶段的脆弱性不在于波动,而在于赌注变得真实可见。

这些项目面临最艰难的抉择:如果过早分配收入,可能会阻碍增长;但若等待过久,代币持有者可能会失去兴趣。

巨头:准备分配

像 Aave、Uniswap 和 Hyperliquid 这样的项目已经跨越了门槛。它们能够产生稳定的收入,拥有去中心化的治理,并受益于强大的网络效应。这些项目不再依赖通胀型代币经济学,已拥有牢固的用户基础和经过市场验证的商业模式。

这些巨头通常不会尝试“包揽一切”。Aave 专注于借贷市场,Uniswap 主导现货交易,而 Hyperliquid 正在构建一个以执行为核心的 DeFi 堆栈。它们的强大来源于可防御的市场定位和运营纪律。

大多数巨头在各自领域内都是领导者。它们的努力通常集中在“扩大蛋糕”——即推动整个市场增长,而不是单纯扩大自己的市场份额。

这些项目是那种可以轻松进行回购并且仍能维持多年运营的类型。尽管它们无法完全免疫波动,但拥有足够的韧性来应对市场的不确定性。

季节性玩家:热闹却缺乏基础

季节性玩家是最引人注目却也最脆弱的类型。它们的收入可能在短时间内与巨头匹敌,甚至超过巨头,但这些收入主要由炒作、投机或短暂的社交趋势推动。

例如,像 FriendTech 和 PumpFun 这样的项目能够在短时间内制造巨大的参与度和交易量,但很少能将这些转化为长期的用户留存或持续的业务增长。

这类项目并非本质上不好。有些可能会调整方向并实现进化,但大多数只是依靠市场势头的短期游戏,而非构建持久的基础设施。

从公开市场中汲取的教训

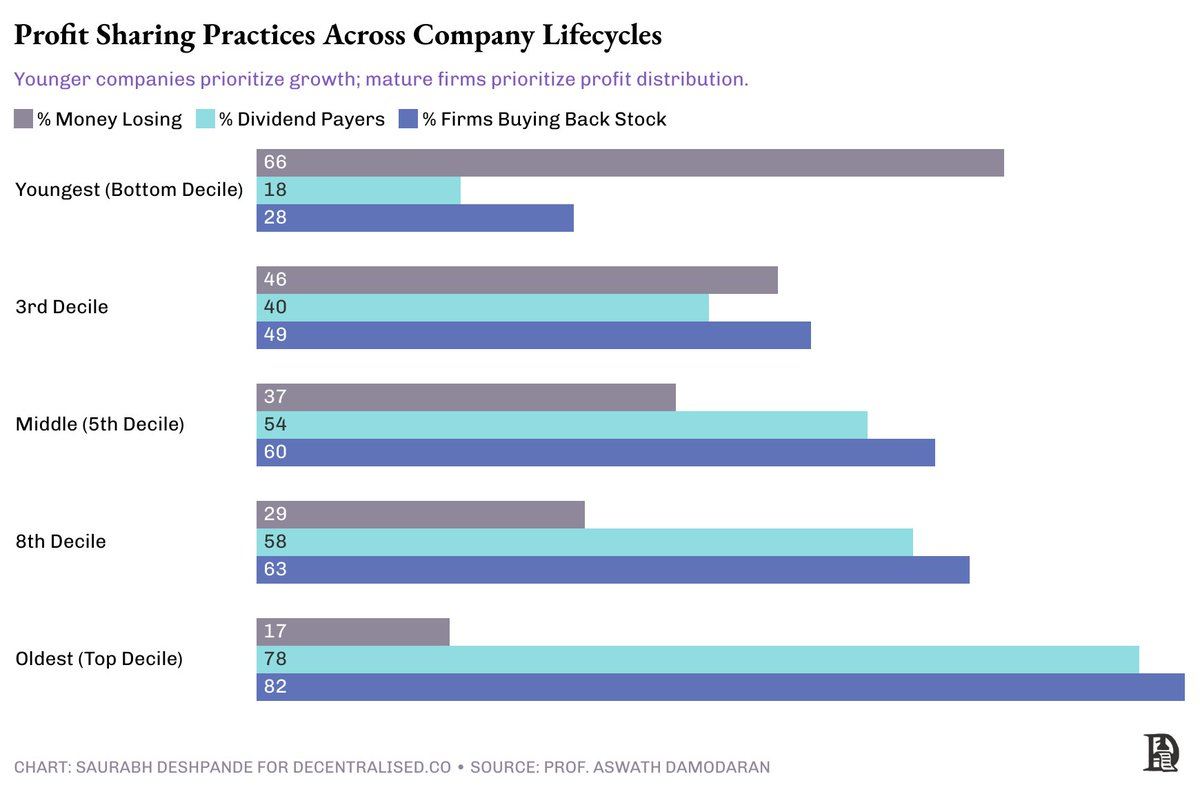

公开股票市场提供了有益的类比。年轻的公司通常会将自由现金流再投资以实现规模化,而成熟的公司则通过分红或股票回购来分配利润。

下图展示了公司如何分配利润。随着公司成长,进行分红和回购的公司数量都会增加。

加密项目可以从中学习。巨头应该进行利润分配,而探索者则应注重保留和复利增长。但并非每个项目都清楚自己属于哪个阶段。

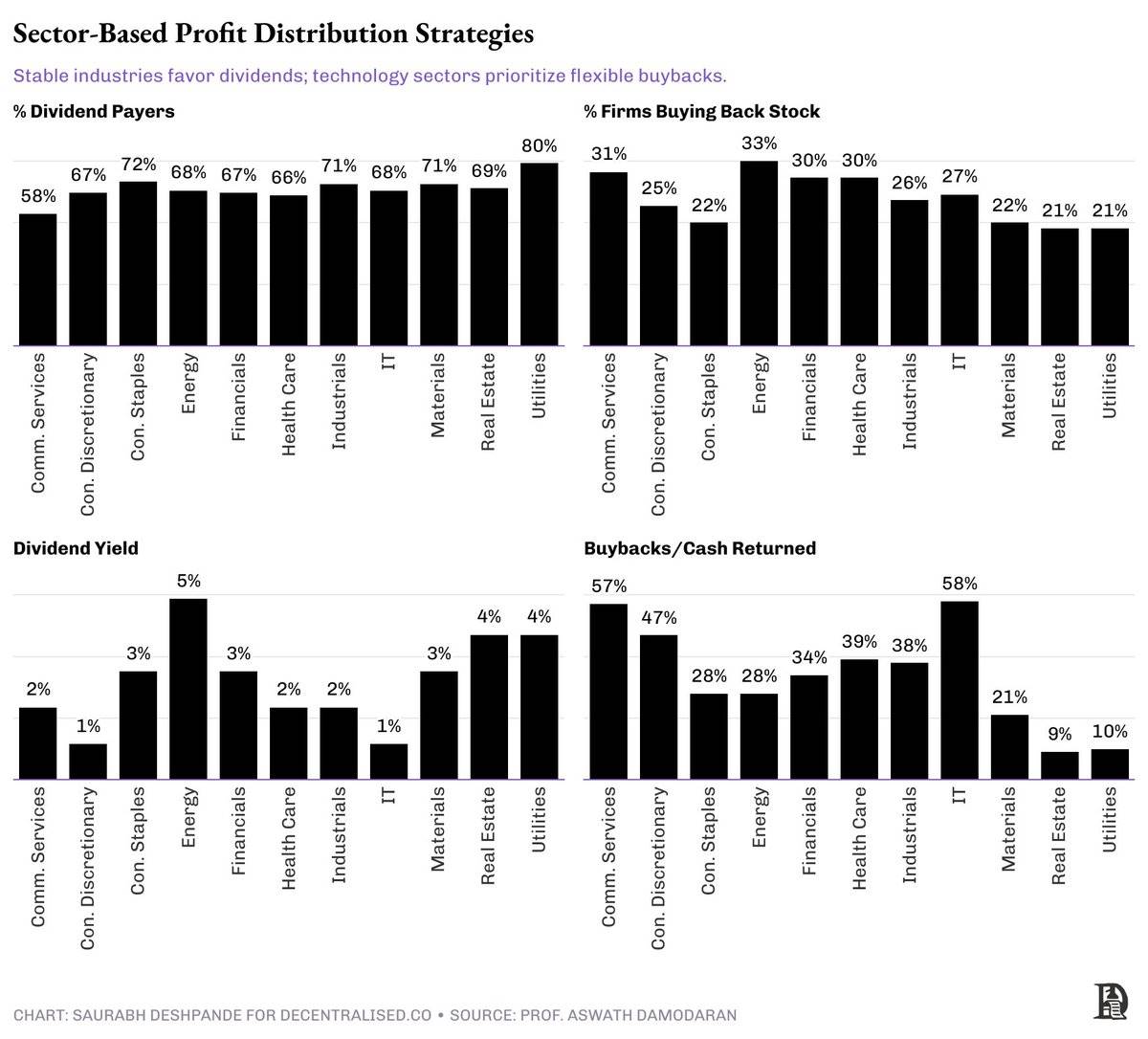

行业特性同样重要。类似公用事业的项目(例如稳定币)更像是消费必需品:稳定且适合分红。这是因为这些公司已存在很长时间,需求模式在很大程度上是可预测的。公司往往不会偏离前瞻性指引或趋势。可预测性使得它们能够与股东持续分享利润。

而高增长的 DeFi 项目则更像科技行业——最佳的价值分配方式是灵活的回购计划。科技公司通常具有更高的季节性波动。大多数情况下,其需求不像一些更传统行业那样具有可预测性。这使得回购成为分享价值的首选方式。

如果一个季度或年度表现优异?通过回购股份将价值传递出去。

分红与回购的对比

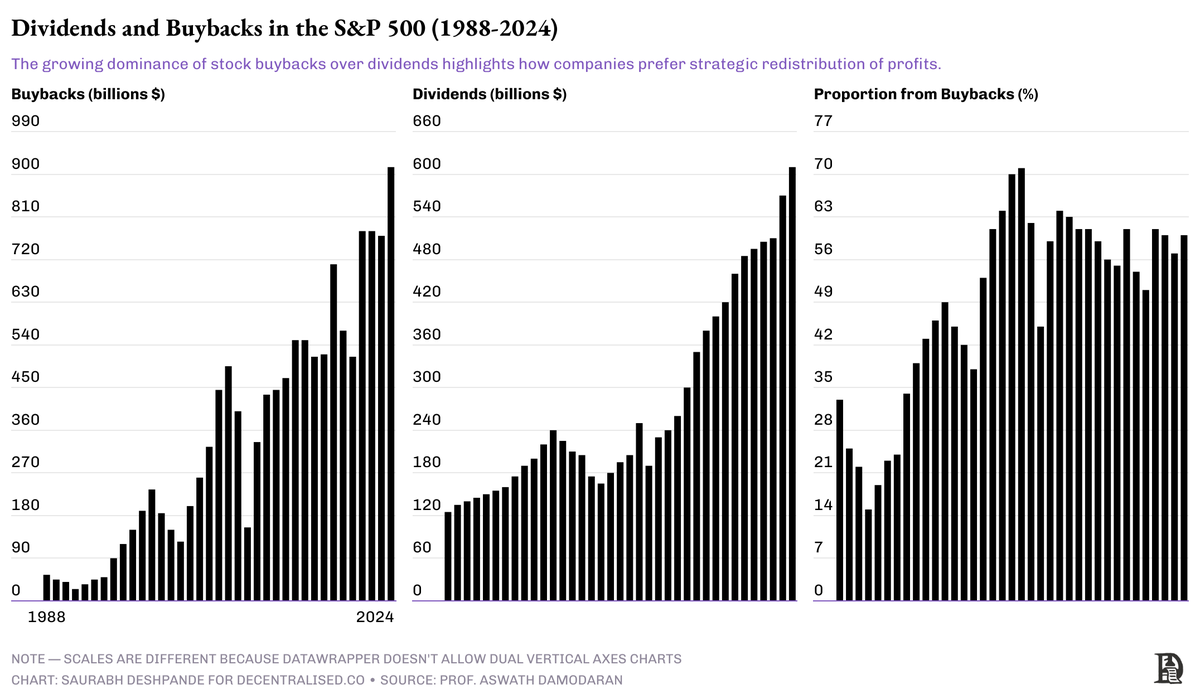

分红具有粘性。一旦承诺支付分红,市场就会期望其保持一致性。而相比之下,回购则更加灵活,允许团队根据市场周期或代币被低估的情况来调整价值分配的时机。从20世纪90年代的约20%利润分配占比,到2024年的约60%,回购在过去几十年中迅速增长。从美元金额来看,自1999年以来,回购的规模就已经超过了分红。

然而,回购也存在一些弊端。如果沟通不当或定价不合理,回购可能会将价值从长期持有者转移到短期交易者手中。此外,治理机制需要非常严密,因为管理层通常有诸如提升每股收益(EPS)等关键绩效指标(KPIs)。当公司用利润回购流通中的股份(即未偿还股份)时,会减少分母,从而人为地抬高EPS数据。

分红和回购各有其适用场景。然而,如果缺乏良好的治理,回购可能会悄悄地让内部人士获益,而社区却因此受损。

良好回购的三大要素:

-

强大的资产储备

-

深思熟虑的估值逻辑

-

透明的报告机制

如果一个项目缺乏这些条件,它可能仍然需要处于再投资阶段,而不是进行回购或分红。

领先项目当前的收入分配实践

-

@JupiterExchange 在代币发布时明确表示:不直接分享收入。在用户增长10倍、拥有足以维持多年运营的资金储备后,他们推出了“Litterbox Trust”——一种非托管的回购机制,目前持有约970万美元的JUP代币。

-

@aave拥有超过9500万美元的资产储备,通过一个名为“Buy and Distribute”(购买与分配)的结构化计划,每周分配100万美元用于回购。这一计划是在经过数月的社区对话后推出的。

-

@HyperliquidX 更进一步,其收入的54%用于回购,46%用于激励流动性提供者(LPs)。迄今为止,已回购超过2.5亿美元的HYPE代币,完全由非风险投资资金支持。

这些项目的共同点是什么?它们都在确保财务基础稳固之后,才开始实施回购计划。

缺失的一环:投资者关系(IR)

加密行业热衷于谈论透明性,但大多数项目仅在有利于自身叙述时才会公开数据。

投资者关系(IR)应成为核心基础设施。项目需要分享的不仅是收入,还包括支出、资金储备(runway)、资产储备策略以及回购执行情况。只有这样,才能建立对长期发展的信心。

这里的目标并不是宣称某种价值分配方式是唯一正确的,而是承认分配方式应与项目的成熟度相匹配。而在加密领域,真正成熟的项目仍然罕见。

大多数项目仍在寻找自己的立足点。但那些做对了的项目——拥有收入、策略和信任的项目——有机会成为这个行业急需的“教堂”(长期稳健的标杆)。

强大的投资者关系是一种护城河。它能够建立信任,减轻市场低迷时期的恐慌,并保持机构资本的持续参与。

理想的IR实践可能包括:

-

季度收入与支出报告

-

实时资产储备仪表盘

-

执行回购的公开记录

-

清晰的代币分配与解锁计划

-

对补助金、薪资和运营支出的链上验证

如果我们希望代币被视为真正的资产,它们需要开始像真正的企业一样进行沟通。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。