In today's world, where blockchain technology is continuously maturing and the ecosystem is becoming increasingly complex, MEV (Maximum Extractable Value), which was originally seen as an incidental vulnerability caused by transaction ordering flaws, is gradually evolving into a highly complex, systematic profit extraction mechanism. Among these, sandwich attacks have garnered significant attention due to their exploitation of transaction ordering rights to insert proprietary transactions before and after target transactions, manipulating asset prices to achieve low-buy high-sell arbitrage. This has made it one of the most controversial and destructive attack methods in the DeFi ecosystem.

1. Basic Concepts of MEV and Sandwich Attacks: Evolution, Current Status, and Cases

Sources and Technical Evolution of MEV:

MEV (Maximum Extractable Value), initially referred to as miner extractable value, refers to the additional economic benefits that miners or validators can obtain by manipulating transaction order, inclusion, or exclusion during the block construction process. Its theoretical foundation lies in the transparency of blockchain transactions and the uncertainty of transaction ordering in the memory pool. With the development of tools such as flash loans and transaction bundling, previously sporadic arbitrage opportunities have gradually been amplified, forming a complete profit extraction chain. From an initial incidental event to a now systematic and industrialized arbitrage model, MEV exists not only on Ethereum but also presents different characteristics across multiple chains such as Solana and Binance Smart Chain.

Principles of Sandwich Attacks:

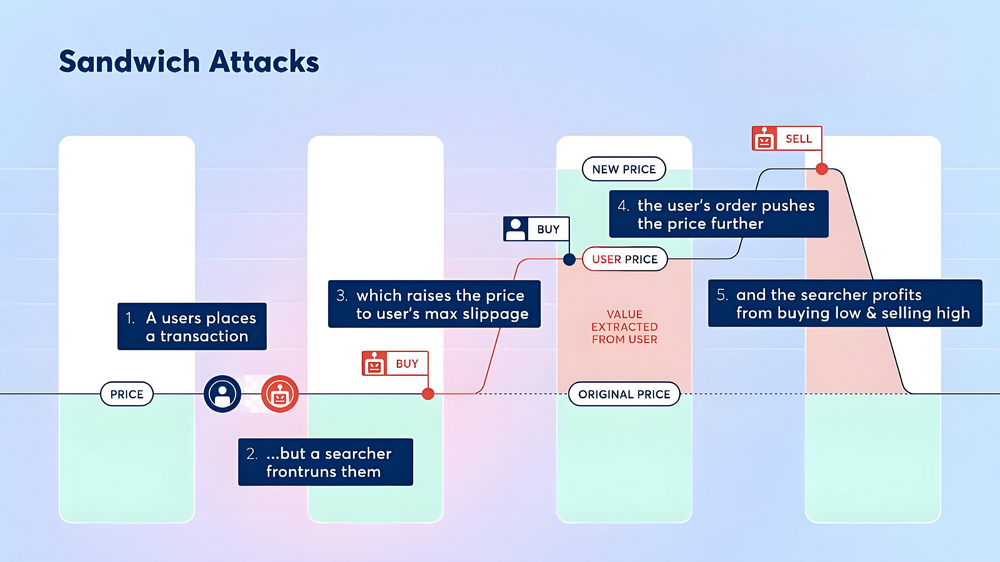

Sandwich attacks are a typical operational method in MEV extraction, where attackers utilize real-time monitoring capabilities of memory pool transactions to submit transactions before and after the target transaction (Victim Transaction), forming a transaction sequence of “front-run—target transaction—back-run,” thereby achieving arbitrage through price manipulation. The core principles include:

Front-Run: When an attacker detects a large or high-slippage transaction, they immediately submit their buy order to push up or lower the market price.

Victim Transaction: The target transaction is executed after the price has been manipulated, resulting in a significant deviation between the actual execution price and the expected price, causing the trader to incur additional costs.

Back-Run: Following the target transaction, the attacker submits a reverse transaction to sell at a high price (or buy at a low price) the assets previously acquired, thereby locking in the price difference profit.

This operation is akin to “sandwiching” the target transaction between the attacker’s two transactions, hence the name “sandwich attack.”

2. Evolution, Current Status, and Cases of MEV Sandwich Attacks

(1) From Sporadic Vulnerabilities to Systematic Mechanisms

Initially, due to inherent deficiencies in transaction ordering mechanisms within blockchain networks, MEV attacks occurred only sporadically and on a small scale. However, with the surge in trading volume in the DeFi ecosystem and the continuous development of high-frequency trading bots and flash loans, attackers began to construct highly automated arbitrage systems, transforming this attack method from sporadic events into a systematic, industrialized arbitrage model. By leveraging high-speed networks and sophisticated algorithms, attackers can deploy front-run and back-run transactions in a very short time, using flash loans to obtain large amounts of capital and completing arbitrage operations within the same transaction. Currently, there are cases on multiple platforms where a single transaction can yield profits of hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars, marking the transition of the MEV mechanism from incidental vulnerabilities to a mature profit extraction system.

(2) Attack Patterns Based on Different Platform Characteristics

Different blockchain networks exhibit varying implementation characteristics of sandwich attacks due to differences in design philosophy, transaction processing mechanisms, and validator structures. For example:

Ethereum: The public and transparent memory pool allows all pending transaction information to be monitored, and attackers often pay higher gas fees to seize transaction packaging order. To address this issue, mechanisms such as MEV-Boost and proposer-builder separation (PBS) have been gradually introduced within the Ethereum ecosystem to reduce the risk of a single node controlling transaction ordering.

Solana: Although Solana does not have a traditional memory pool, the relative concentration of validator nodes means that some nodes may collude with attackers to leak transaction data, allowing attackers to quickly capture and exploit target transactions, leading to frequent and profitable sandwich attacks within this ecosystem.

Binance Smart Chain (BSC): Although the maturity of the BSC ecosystem differs from that of Ethereum, its lower transaction costs and simplified structure also provide space for certain arbitrage activities, where various bots can similarly employ strategies to extract profits in this environment.

These cross-chain environmental differences encourage unique attack methods and profit distributions across different platforms, while also raising higher demands for prevention strategies.

(3) Latest Data and Cases

Uniswap Platform Case: On March 13, 2025, a transaction on Uniswap V3 saw a trader incur a loss of up to $732,000 while conducting a transaction worth approximately 5 SOL due to a sandwich attack. This incident illustrates how attackers utilized front-run transactions to seize block packaging rights, inserting transactions before and after the target transaction, causing the victim's actual execution price to deviate significantly from expectations.

Continuous Evolution on the Solana Chain: In the Solana ecosystem, sandwich attacks not only occur frequently but also exhibit new attack patterns. Some validators are even suspected of colluding with attackers by leaking transaction data to gain prior knowledge of user trading intentions, thereby implementing precise strikes. This has led to some attackers on the Solana chain seeing their profits grow from tens of millions to over a hundred million dollars within just a few months.

These data and cases indicate that MEV sandwich attacks are no longer incidental events but have manifested systematic and industrialized characteristics alongside the increasing transaction volume and complexity of blockchain networks.

3. Operational Mechanism and Technical Challenges of Sandwich Attacks

As the overall market trading volume continues to expand, the frequency of MEV attacks and the profit per transaction are on the rise. In some platforms, the transaction cost-to-revenue ratio of sandwich attacks has even reached high levels. The following are several conditions that need to be met to implement a sandwich attack:

Transaction Monitoring and Capture: Attackers must monitor pending transactions in the memory pool in real-time to identify transactions with significant price impact.

Competition for Priority Packaging Rights: By utilizing higher gas fees or priority fees, attackers can preemptively package their transactions into blocks, ensuring execution before and after the target transaction.

Precise Calculation and Slippage Control: When executing front-run and back-run transactions, precise calculations of transaction volume and expected slippage must be made to both drive price fluctuations and ensure that the target transaction does not fail due to exceeding the set slippage.

Implementing such attacks requires not only high-performance trading bots and rapid network responses but also the payment of high miner bribe fees (e.g., increasing gas fees) to ensure transaction priority. These costs constitute the primary expenditure for attackers, and in a fiercely competitive environment, multiple bots may simultaneously attempt to seize the same target transaction, further compressing profit margins. These technical and economic barriers continuously drive attackers to update their algorithms and strategies while also providing a theoretical basis for the design of prevention mechanisms.

4. Industry Response and Prevention Strategies

Prevention Strategies for Ordinary Users:

Set Reasonable Slippage Protection: When submitting transactions, users should set slippage tolerance reasonably based on current market volatility and expected liquidity conditions to avoid transaction failures due to overly low settings and to prevent malicious sandwiching due to overly high settings.

Use Privacy Trading Tools: Utilizing technologies such as private RPCs and order bundling auctions can hide transaction data outside the public memory pool, reducing the risk of being attacked.

Technical Improvement Suggestions at the Ecosystem Level:

Transaction Ordering and Proposer-Builder Separation (PBS): By separating the responsibilities of block construction and block proposal, the control of transaction ordering by a single node can be limited, thereby reducing the likelihood of validators exploiting ordering advantages for MEV extraction.

MEV-Boost and Transparency Mechanisms: Introducing third-party relay services and MEV-Boost solutions can make the block construction process transparent, reducing reliance on a single node and enhancing overall competitiveness.

Off-chain Order Flow Auctions and Outsourcing Mechanisms: Utilizing outsourced orders (e.g., CoW protocol) and order flow auction mechanisms can achieve bulk matching of orders, increasing the likelihood of users obtaining the best prices while making it difficult for attackers to operate independently.

Smart Contract and Algorithm Upgrades: Leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies can enhance real-time monitoring and predictive capabilities for abnormal fluctuations in on-chain data, helping users to avoid risks in advance.

As the DeFi ecosystem continues to expand, with increasing transaction volume and complexity, MEV and its related attack methods will face more technical confrontations and economic games. In the future, beyond improvements in technical means, how to reasonably allocate economic incentives while ensuring decentralization and network security will become an important topic of common concern in the industry.

5. Conclusion

MEV sandwich attacks have evolved from initial incidental vulnerabilities into a systematic profit extraction mechanism, posing a severe challenge to the DeFi ecosystem and the security of user assets. The latest cases and data from 2025 indicate that the risks of sandwich attacks remain present and are continuously escalating on mainstream platforms such as Uniswap and Solana. To protect user assets and market fairness, the blockchain ecosystem needs to work collaboratively on technological innovation, transaction mechanism optimization, and regulatory coordination. Only in this way can the DeFi ecosystem find a balance between innovation and risk, achieving sustainable development.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。