原文作者:Andy Greenberg

原文编译:比推 BitpushNews Tracy、Alvin

作为一名美国联邦特工,Tigran Gambaryan 开创了现代加密货币调查。后来在币安,他陷入了世界上最大的加密货币交易所和决心让其付出代价的政府的中间。

2024 年 3 月 23 日上午 8 点,Tigran Gambaryan 在尼日利亚阿布贾的沙发上醒来,从黎明前的祈祷开始,他就一直在那里打瞌睡。他周围的房子经常伴随着附近发电机的嗡嗡声,现在却异常安静。在那种寂静中,Gambaryan 所处境况的残酷现实近一个月来每天早上都涌入他的脑海:他和他在加密货币公司币安的同事 Nadeem Anjarwalla 被扣为人质,无法获得自己的护照。他们在军事警卫的看守下,被关押在尼日利亚政府拥有的一栋被铁丝网围起来的院落中。

Gambaryan 从沙发上站了起来。这位 39 岁的亚美尼亚裔美国人身穿一件白色 T 恤,身材结实,肌肉发达,右臂上布满了东正教纹身。他平时剃光头,修剪整齐的黑胡子由于一个月没刮了,现在变得又短又乱。Gambaryan 找到了大院的厨师,问她能不能给他买点香烟。然后他走进房子的内部庭院,开始焦躁不安地走来走去,给他的律师和币安的其他联系人打电话,重新开始他每天的努力,用他的话说,就是「他妈地解决这一问题」。

就在前一天,这两名币安员工和他们的加密货币巨头雇主被告知,他们即将被指控逃税的罪名。这两个人似乎被夹在了一场官僚冲突的中间,冲突发生在一个不负责任的外国政府和加密货币经济中最具争议的参与者之间。现在,他们不仅被强行关押,而且看不到尽头,还被指控为罪犯。

Gambaryan 在电话里说了两个多小时,庭院开始被升起的太阳炙烤。当他终于挂断电话回到屋里时,他仍然没有看到 Anjarwalla 的任何踪迹。那天早上黎明前,Anjarwalla 去了当地的清真寺祈祷,陪同他的看守人对他严加看管。当 Anjarwalla 回到屋里时,他告诉 Gambaryan 他要回楼上睡觉。

从那时起已经过去了几个小时,所以 Gambaryan 上到二楼的卧室去看看他的同事。他推开门,发现 Anjarwalla 似乎睡着了,他的脚从床单下伸出来。Gambaryan 在门口叫他,但没有得到回应。有那么一刻,他担心 Anjarwalla 可能又要惊恐发作了——这位年轻的英裔肯尼亚币安高管已经在 Gambaryan 的床上睡了好几天,他太焦虑了,不敢独自过夜。

Gambaryan 穿过黑暗的房间——他听说这所房子的政府看管人拖欠电费,发电机缺少柴油,所以全天停电很常见——他把手放在毯子上。奇怪的是,毯子沉了下去,好像下面没有真正的人体。

Gambaryan 拉开被单。他发现下面有一件 T 恤,里面塞着一个枕头。他低头看了看从毯子里伸出的脚,现在发现那实际上是一只袜子,里面有一个水瓶。

Gambaryan 没有再叫 Anjarwalla,也没有搜查房子。他已经知道他的币安同事和狱友已经逃走了。他也立即意识到,自己的处境将变得更糟。他还不知道情况会更糟——他将被关进尼日利亚监狱,被指控犯有洗钱罪,可被判处 20 年监禁,即使他的健康状况恶化到濒临死亡,也无法获得医疗服务,同时还被用作数十亿美元加密货币勒索计划的棋子。

那一刻,他只是默默地坐在床上,在离家 6,000 英里的黑暗中,考虑着他现在完全孤身一人的事实。

TIGRAN GAMBARYAN 不断加剧的尼日利亚噩梦至少部分源于一场持续了十五年的冲突。自从神秘的中本聪于 2009 年向世界揭示比特币以来,加密货币就承诺了一种自由主义的圣杯:不受任何政府控制的数字货币,不受通货膨胀的影响,可以肆无忌惮地跨越国界,仿佛它存在于一个完全不同的维度。然而,今天的现实是,加密货币已经成为一个价值数万亿美元的产业,很大程度上由拥有华丽办公室和雇有高薪高管的公司经营——这些国家的法律和执法机构能够对加密货币公司及其员工施加压力,就像他们对任何其他的现实世界中的行业一样。

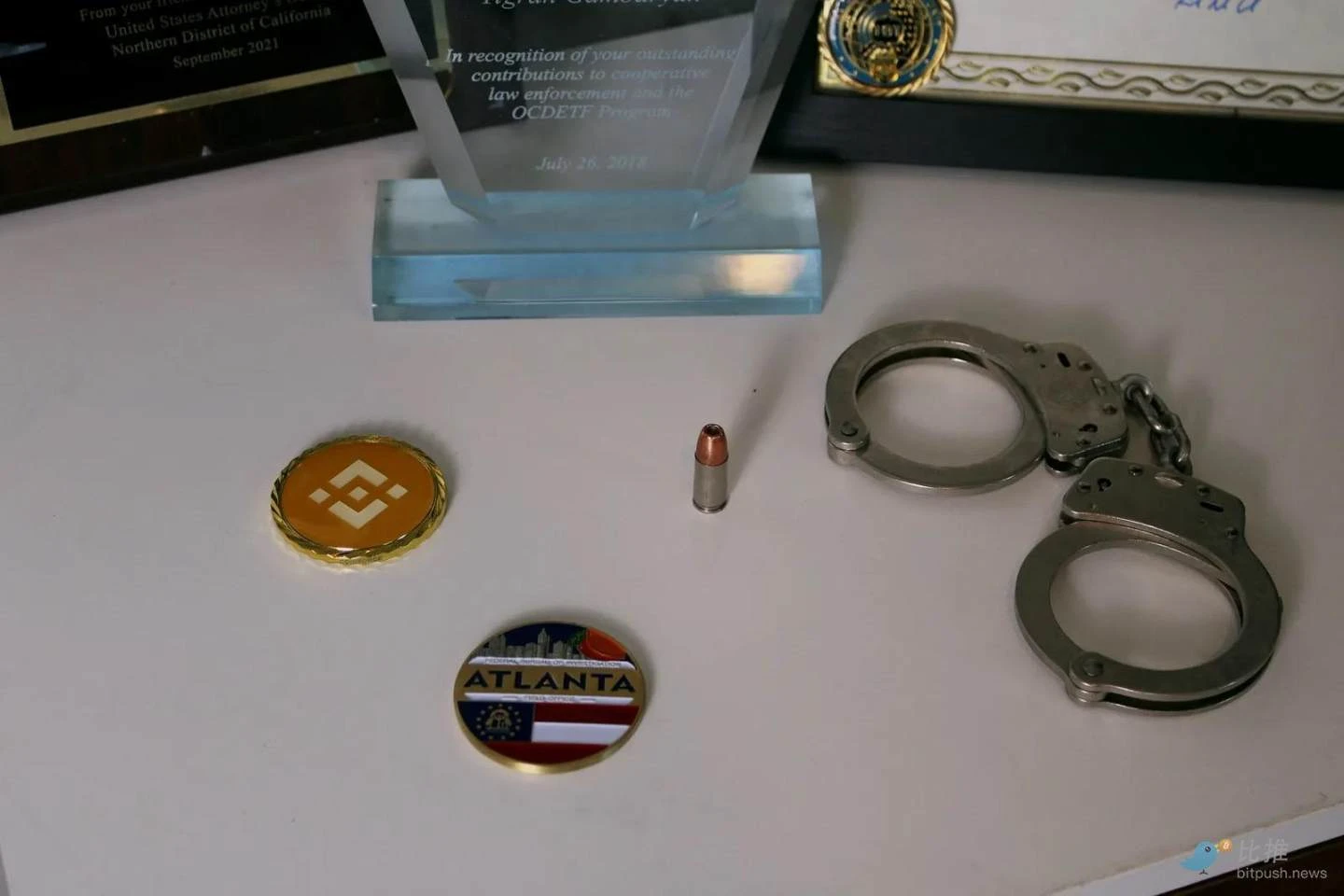

在成为全球最知名的受害者之一,遭遇无序金融科技与全球执法冲突的牺牲品之前,Gambaryan 曾以另一种方式体现这一冲突:作为全球最有效且最具创新性的加密货币专职执法人员之一。在 2021 年加入 Binance 之前的十年,Gambaryan 一直担任美国国税局刑事调查局(IRS-CI)的特别探员,负责执行税务机关的执法工作。在 IRS-CI 任职期间,Gambaryan 开创了通过解析比特币区块链追踪加密货币并识别嫌疑人的技术。他凭借这一「追踪资金」战术,摧毁了一个又一个网络犯罪阴谋,彻底颠覆了比特币匿名性的神话。

从 2014 年开始,在 FBI 查封丝绸之路暗网毒品市场后,正是 Gambaryan 追踪了比特币,揭露了两名腐败的联邦探员,这些探员在调查该市场时,偷取了超过 100 万美元——这是区块链证据首次被纳入刑事起诉书。接下来的几年里,Gambaryan 帮助追踪了从首个加密货币交易所 Mt. Gox 被盗的价值 5 亿美元的比特币,最终确认了一群俄罗斯黑客是这起盗窃事件的幕后黑手。

2017 年,Gambaryan 与区块链分析初创公司 Chainalysis 合作,创造了一种秘密的比特币追踪方法,这一方法成功找到了并帮助 FBI 查封了托管 AlphaBay 的服务器。AlphaBay 是一个暗网犯罪市场,估计其规模是丝绸之路的 10 倍。几个月后,Gambaryan 在摧毁加密货币资助的儿童性虐待视频网络「Welcome to Video」时发挥了关键作用,这是迄今为止最大规模的此类市场。此次行动导致全球 337 名用户被捕,23 名儿童被救出。

最终,在 2020 年,Gambaryan 和另一名 IRS-CI 探员追踪并查封了近 70,000 枚比特币,这些比特币是多年前被一名黑客从丝绸之路偷走的。按照今天的价格,这些比特币价值 70 亿美元,成为历史上最大规模的任何货币类型犯罪没收,流入美国财政部。

「他参与的案件几乎涵盖了当时所有最大的加密货币案件,」前美国检察官 Will Frentzen 说,他曾与 Gambaryan 紧密合作,并起诉了 Gambaryan 揭露的犯罪。「他在调查上非常创新,采用了许多人未曾想到的方式,在对待获得荣誉方面也非常无私。」在与加密货币犯罪的斗争中,Frentzen 表示:「我认为没有人比他对这一领域产生更大的影响。」

在经历了那一段传奇的职业生涯后,Gambaryan 转向了私人部门,做出了令许多曾与他共事的政府同事感到震惊的决定。他成为了 Binance 调查团队的负责人。Binance 是一家庞大的加密货币交易所,处理着数百亿美元的日常交易,并且以对用户是否违反法律漠不关心而闻名。

当 Gambaryan 于 2021 年秋季加入 Binance 时,这家公司已经成为美国司法部调查的对象。最终,调查结果显示,Binance 处理了数十亿美元的交易,这些交易违反了反洗钱法律,并绕过了对伊朗、古巴、叙利亚以及俄罗斯占领的乌克兰地区的国际制裁。司法部还指出,该公司直接处理了来自俄罗斯暗网犯罪市场 Hydra 的超过 1 亿美元加密货币交易,甚至在某些情况下,资金来源包括出售儿童性虐待材料和资助被认定为恐怖组织的资金。

Gambaryan 的一些老同事私下里对他转行表示不满,甚至认为他「卖身投敌」。然而,Gambaryan 坚信自己其实是在承担职业生涯中最重要的角色。作为 Binance 在经历多年快速扩张后,开始着手清理公司形象的一部分,Gambaryan 在公司内部组建了一个新的调查团队,他从 IRS-CI 和世界各地的其他执法机构招募了许多顶尖特工,并帮助 Binance 与执法机关展开了前所未有的合作。

Gambaryan 表示,通过分析交易量超过纽约证券交易所、伦敦证券交易所和东京证券交易所总和的数据,他的团队成功帮助全球范围内破获了儿童性虐待、恐怖分子和有组织犯罪等案件。「我们协助过全球成千上万的案件。我在 Binance 的影响力可能比在执法部门时还要大,」 Gambaryan 曾告诉我,「我为我们所做的工作感到非常自豪,如果有人质疑我加入 Binance 的决定,我随时愿意辩论。

尽管 Gambaryan 帮助 Binance 打造了一个更加守法的形象,但这一转变并不能抹去公司作为一个不法交易所的历史,也无法让它免受过去犯罪行为的后果。2023 年 11 月,美国司法部长梅里克·加兰在新闻发布会上宣布,Binance 同意支付 43 亿美元的罚款和没收款项,这是美国刑事司法历史上最大的企业处罚之一。公司创始人兼 CEO 赵长鹏个人被罚款 1.5 亿美元,并被判处四个月监禁。

美国并非唯一对 Binance 有不满的国家。到了 2024 年初,尼日利亚也开始指责该公司,不仅因为它在美国认罪协议中承认的合规违规行为,还因为 Binance 被指责加剧了尼日利亚货币奈拉的贬值。2023 年底至 2024 年初,奈拉贬值近 70%,尼日利亚人纷纷将本国货币兑换为加密货币,尤其是与美元挂钩的「稳定币」。

Eurasia Group 的非洲地区负责人 Amaka Anku 表示,奈拉贬值的真正原因是尼日利亚新总统 Bola Tinubu 政府放松了奈拉与美元之间的汇率限制,并且尼日利亚中央银行的外汇储备出乎意料地少。然而,当奈拉开始贬值时,加密货币作为一种不受监管的方式来抛售奈拉,进一步加剧了贬值压力。「你不能说 Binance 或任何加密交易所直接导致了这一贬值,」Anku 表示,「但它们确实加剧了这一过程。

多年来,加密货币的支持者一直设想,萨托希的发明将为面临通货膨胀危机的国家公民提供一个避风港。这个时刻终于到来了,而尼日利亚这个非洲最大经济体的政府对此愤怒不已。2023 年 12 月,尼日利亚国会的一个委员会要求 Binance 的高层出席在首都阿布贾举行的听证会,解释他们如何纠正所涉嫌的错误。为应对这一局面,Binance 召集了尼日利亚代表团,作为该公司与全球执法机构和政府合作承诺的象征,Tigran Gambaryan 这位前联邦特工和明星调查员自然成了代表团的一员。

然而,在采取胁迫和绑架人质等极端手段之前,(犯罪者)首先提出了索要贿赂的要求。

2023 年 1 月,Gambaryan 刚到阿布贾几天,行程顺利。为了表达善意,他与尼日利亚经济与金融犯罪委员会(EFCC)的调查员们见了面。EFCC 基本上是 Gambaryan 曾在美国国税局工作时的对应机构,负责打击诈骗、调查政府腐败等任务,并讨论了如何为该机构员工提供加密货币调查培训的可能性。接着,他参加了与 Binance 高层和尼日利亚众议院成员的一次圆桌会议,大家在和气的气氛中相互承诺,会一起解决分歧。

Gambaryan 到达尼日利亚时,是 EFCC 的侦探 Olalekan Ogunjobi 在机场接待了他。Ogunjobi 阅读过 Gambaryan 的职业经历,并表示非常钦佩他作为联邦特工的传奇成就。在整个行程中,Ogunjobi 几乎每天晚上都会与 Gambaryan 在酒店——阿布贾 Transcorp Hilton 酒店——共进晚餐。Gambaryan 与 Ogunjobi 分享了关于加密犯罪调查的经验,如何处理案件,如何组建专案组等。他们交换了很多调查经验。当 Gambaryan 把他所写的《Tracers in the Dark》一书赠送给 Ogunjobi,并签名时,Ogunjobi 请求他在书上签字。

有一天晚上,当 Gambaryan 和 Ogunjobi 以及一群 Binance 同事正在餐桌上用餐时,Binance 的一名员工接到了公司律师的电话。在寒暄过后,律师告诉 Gambaryan,实际上与尼日利亚官员的会面并不像看上去那么友好。官员们现在要求支付 1.5 亿美元,以解决 Binance 在尼日利亚的问题——并要求通过加密货币支付,直接转账到官员们的加密钱包中。更令人震惊的是,官员们暗示,直到这笔款项到位,Binance 团队才可以离开尼日利亚。

Gambaryan 感到非常震惊,他甚至没有时间向 Ogunjobi 解释或告别,便急忙收拾起 Binance 的员工,匆匆离开餐厅,回到 Transcorp Hilton 酒店的会议室,商讨下一步的应对方案。支付这笔显而易见的贿赂款项将违反美国的《海外反腐败法》(Foreign Corrupt Practices Act)。如果拒绝,他们可能会被无限期拘留。最终,团队决定采取第三种选择:立即离开尼日利亚。他们整晚都在会议室里紧急策划,计划如何让所有 Binance 员工尽快登上飞机,改变航班,将离开时间提前到第二天早晨。

第二天早晨,Binance 团队在酒店二楼集合,行李已经打包好,他们尽量避免经过大厅,以防尼日利亚官员可能在大厅等着他们,阻止他们离开。大家打出租车赶往机场,紧张地通过安检,顺利登机回国,整个过程中没有发生任何问题。大家都觉得自己仿佛躲过了一场灾难。

回到亚特兰大的郊区后不久,Gambaryan 接到了 Ogunjobi 的电话。Gambaryan 表示,Ogunjobi 对 Binance 团队遭受行贿要求感到非常失望,并且为尼日利亚同胞的行为感到震惊。Ogunjobi 建议 Gambaryan 将这次行贿事件报告给尼日利亚当局,要求他们展开反腐调查。

最终,Ogunjobi 安排了 Gambaryan 与 EFCC 官员 Ahmad Sa’ad Abubakar 的通话。Abubakar 被介绍为尼日利亚国家安全顾问 Nuhu Ribadu 的得力助手。Ogunjobi 告诉 Gambaryan,Ribadu 是反腐斗士,甚至曾在 TEDx 上做过演讲。现在,Ribadu 邀请 Gambaryan 亲自与他见面,解决 Binance 在尼日利亚的问题,并彻查行贿事件的真相。

Gambaryan 将电话中的情况告诉了他的 Binance 同事,这听起来似乎是解决公司在尼日利亚困境的一个机会。于是,Binance 的高管和 Gambaryan 开始考虑,或许他可以利用这个邀请回到尼日利亚,解开公司与尼日利亚政府日益复杂的关系。尽管这个想法听起来十分冒险——毕竟几周前他们才匆忙逃离了这个国家——Gambaryan 相信他收到了一个有权势官员的友好邀请,并且还得到了朋友 Ogunjobi 的个人保证。Binance 当地的工作人员也告诉 Gambaryan,他们经过核实,认为这个解决方案是可靠的。

Gambaryan 将行贿事件和回尼日利亚的邀请告诉了妻子 Yuki。对于她来说,这个提议显然非常危险。她一再要求 Gambaryan 不要去。

现在 Gambaryan 承认,或许他当时依然保留着作为美国联邦探员的思维方式——那种带有责任感和保障的身份。「我想那是以前留下来的部分:当职责召唤时,你就去做,」他说。「我被要求去。」

于是,在他现在认为是人生中最不明智的决定之一,Gambaryan 收拾好行李,亲吻了 Yuki 和两个小孩,2 月 25 日清晨便出发,搭上飞往阿布贾的航班。

第二次的行程从 Ogunjobi 的机场接机开始,Ogunjobi 再次向他保证,在驱车前往 Transcorp Hilton 酒店的途中以及晚餐时都一再安慰他。这次,陪同 Gambaryan 的只有 Binance 东非地区经理 Nadeem Anjarwalla,一位刚毕业的斯坦福大学英籍肯尼亚人,家中有个在内罗毕的婴儿。

然而,当 Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 第二天走进与尼日利亚官员的会议时,他们惊讶地发现,Abubakar 带着 EFCC 和尼日利亚中央银行的工作人员一起出席。很快,会议的焦点变得明确:这次会议并非讨论尼日利亚的腐败问题。会议开始时,Abubakar 询问了 Binance 与尼日利亚执法机关的合作情况,随即将话题转向了 EFCC 要求获取 Binance 尼日利亚用户的交易数据。Abubakar 表示,Binance 仅提供了过去一年的数据,而不是他所要求的所有数据。Gambaryan 感到自己被突袭了,他解释说这是因为临时请求导致的疏忽,并承诺会尽快提供所有需要的数据。尽管 Abubakar 显得有些不满,会议还是继续进行,最后大家友好地交换了名片。

Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 被留在走廊里,等待下一次的约见。过了一会儿,Anjarwalla 去洗手间。当他回来时,他说他从附近的会议室里听到了一些刚刚见过的官员发怒的声音,Gambaryan 记得他是这么说的。

等了将近两个小时后,Ogunjobi 回来了,带着他们进入了另一个会议室。Gambaryan 记得,这间会议室里的官员们神情凝重,气氛异常严肃,大家都默默坐着,似乎在等着某个人的到来——Gambaryan 不知道那个人是谁。他注意到 Ogunjobi 的脸上露出了震惊的表情,而且不敢与他对视。「到底发生了什么?」他心里想着。

这时,一位名叫 Hamma Adama Bello 的中年男子走进了房间。他是 EFCC 的一名官员,穿着灰色西装,胡子拉碴,看起来大约四十多岁。他没有打招呼,也没有提问,直接将一个文件夹放到桌子上,立刻开始训斥道,Gambaryan 记得他说的是:Binance 正在「摧毁我们的经济」,并且为恐怖主义提供资金。

接着,他告诉 Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 将会发生什么:他们会被带回酒店收拾行李,然后转移到另一个地方,那里会有更多的 EFCC 官员和一些中央银行人员,直到 Binance 交出所有涉及每一个曾经使用过该平台的尼日利亚人的交易数据。

Gambaryan 感到心跳加速,他立即表示,他没有权限,也无法提供这么大量的数据——他此行的目的,实际上是为了向 Bello 的机构报告行贿的情况。

Bello 听到行贿的事时似乎有些吃惊,像是第一次听说这种事情,但很快就不再理会。会议结束了。Gambaryan 赶紧发了一条短信给 Binance 的首席合规官 Noah Perlman,告诉他他们可能会被拘留。接着,官员们拿走了他们的手机。

两人被带到外面的一辆黑色兰德巡洋舰上,车窗上贴着深色窗膜。SUV 将他们送回了 Transcorp Hilton 酒店,并被带回各自的房间——Anjarwalla 跟着 Bello 和另外一名官员走,Gambaryan 则由 Ogunjobi 带着。他们被告知打包行李。Gambaryan 记得对 Ogunjobi 说:「你知道这事有多糟吧?」

Ogunjobi 几乎不敢直视他说话,回答道:「我知道,我知道。」

然后,兰德巡洋舰将他们送到了一个大型两层楼的房子,这个房子位于一个有围墙的大院里,里面有大理石地板,足够容纳两名 Binance 员工和几名 EFCC 官员的卧室,还有一位私人厨师。Gambaryan 后来才知道,这个房子是国家安全顾问 Ribadu 的政府指定住所,但 Ribadu 选择住在自己的家里,把这个地方留给官方使用——在此次事件中,作为临时关押他们的地方。

那天晚上,Bello 没有再提出其他要求。Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 吃了由房子里厨师做的尼日利亚炖菜后,被告知可以休息。Gambaryan 躺在床上,心情焦虑不安,几乎陷入恐慌,因为他没有手机,无法与外界联系,甚至无法告诉家人自己在哪里。

直到凌晨两点,他才终于入睡,几小时后,在清晨的穆厄辛祷告声中醒来。由于过于焦虑,他无法再躺在床上,于是走到房子的院子里,抽烟思考自己现在的困境:他成了人质,陷入了自己一生致力于打击的金融犯罪之中。

但除了这份讽刺感,更令他感到压倒性的,是那种完全的未知感。「我到底会怎样?Yuki 会经历什么?」他想着妻子,内心充满焦虑。「我们会在这里待多久?」

Gambaryan 在院子里站着抽烟,直到太阳升起。

接着是审讯。

早餐由厨师准备,但 Gambaryan 因压力过大,根本没胃口吃。Bello 坐下来与他们交谈,告诉他们,要释放他们,Binance 必须交出所有关于尼日利亚用户的数据,并且禁止尼日利亚用户进行点对点交易。点对点交易是 Binance 平台上的一项功能,允许交易者根据他们部分控制的汇率发布加密货币出售广告,尼日利亚官员认为这在一定程度上加剧了奈拉的贬值。

除了这些要求外,会议室里还有一个未明确说出的要求:Binance 需要支付一笔巨额款项。当 Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 被扣押时,尼日利亚方面通过秘密渠道与 Binance 高层沟通,公司得知他们要求支付数十亿美元。据参与谈判的人士透露,政府官员甚至曾公开对 BBC 表示,这笔罚款将至少达到 100 亿美元,是 Binance 向美国支付的历史最高和解金额的两倍多。(根据几位知情人士的说法,Binance 确实曾提出过「定金」方案,金额基于公司在尼日利亚的税务责任估算,但这些提议从未被接受。与此同时,Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 被拘留后的第二天,美国使馆收到了来自 EFCC 的一封奇怪信件,信中表示 Gambaryan 被拘留「仅仅是为了进行建设性对话」,并且「自愿参与这些战略性对话」。

Gambaryan 一再向 Bello 解释,他在 Binance 的业务决策中没有实际权力,无法满足他提出的要求。Bello 听后并没有改变语气,继续长篇大论地指责 Binance 对尼日利亚造成的损害,并宣称尼日利亚应当得到赔偿。Gambaryan 回忆,Bello 有时还炫耀他携带的枪支,并展示了自己在弗吉尼亚州 Quantico 与 FBI 合作训练的照片,似乎在显示自己的权威和与美国的联系。

Ogunjobi 也参与了审问。Gambaryan 说,他比 Bello 更加安静、尊重,但已不再是那个充满敬意的学生。当 Gambaryan 提到自己曾为尼日利亚执法部门提供过诸多帮助时,Ogunjobi 回应称,他在 LinkedIn 上看到评论说,Binance 雇佣他只是为了制造合法性的假象,这一番话让 Gambaryan 感到震惊,尤其是经过他们之前的长时间交谈后。

气愤且无法满足尼日利亚方面要求的 Gambaryan 要求见律师、联系美国大使馆并归还手机,但所有请求都被拒绝,虽然他被允许在警卫在场的情况下拨打给妻子的电话。

处于与 EFCC 官员的僵局中,Gambaryan 告诉他们,除非允许他见律师并与大使馆联系,否则他不会进食。他开始了绝食,困在这个房子里,被政府人员和警卫看守,整天呆坐在沙发上看尼日利亚电视。经过五天的绝食后,官员们终于让步。

他和 Anjarwalla 被归还了手机,但被告知不得与媒体联系,护照也被扣留。随后,他们被允许与 Binance 雇佣的当地律师会面。在一周的拘留后,Gambaryan 被送往尼日利亚政府大楼,与当地的外交官见面。外交官表示他们会关注 Gambaryan 的情况,但目前为止,没办法让他自由。

接着,他们开始过上了「土拨鼠日」般的日常生活,正如 Gambaryan 后来告诉妻子的一样,四处打转。房子宽敞而干净,但破旧不堪,屋顶漏水,很多天没有电。Gambaryan 和厨师及一些看管人员成了朋友,和他们一起看盗版的《降世神通:最后的气宗》剧集。Anjarwalla 则开始每天做瑜伽,喝厨师为他做的果昔。

Anjarwalla 看起来比 Gambaryan 更难以承受他们被囚禁的焦虑,他为错过儿子第一岁生日而感到沮丧。尼日利亚方面扣下了他的英国护照,但他们没有意识到 Anjarwalla 还持有他的肯尼亚护照。他和 Gambaryan 开玩笑说要逃跑,但 Gambaryan 表示,他从未认真考虑过这一点。他告诉自己,Yuki 曾叮嘱他「不要做傻事」,他并不打算冒险。

某一天,Anjarwalla 躺在沙发上告诉 Gambaryan 自己感觉不舒服,浑身冰冷。Gambaryan 给他盖了很多毛毯,但他仍然在颤抖。最终,尼日利亚方面带着 Anjarwalla 和 Gambaryan 去医院,乘坐另一辆黑色的 Land Cruiser,给 Anjarwalla 做了疟疾检测。检测结果显示为阴性,医生告诉 Anjarwalla 其实他只是发生了恐慌性发作。从那以后,每晚,Gambaryan 说,Anjarwalla 都会睡在他身边,因为他太害怕一个人睡觉。

在 Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla 被囚禁的第二周,Binance 同意了要求,关闭了其尼日利亚的对等交易功能,并撤销了所有奈拉交易。EFCC 的官员告诉 Gambaryan 和 Anjarwalla,准备好打包行李,准备释放他们。两人听到这个好消息后很认真,Gambaryan 甚至用手机拍摄了房子的录像,作为这段奇异生活的纪念。

然而,在他们即将被释放前,政府看管人员将他们带到了 EFCC 办公室。该机构主席要求确认 Binance 是否已交出所有有关尼日利亚用户的数据。当得知 Binance 没有提供时,他立即撤销了释放决定,并将两人送回宾馆。

此时,首先是加密货币网站 DLNews 报道了有两名 Binance 高管被拘留在尼日利亚,虽然没有透露姓名。几天后,《华尔街日报》和《连线》也确认了被拘留的是 Anjarwalla 和 Gambaryan。

Bello 对新闻泄露感到愤怒,Gambaryan 回忆说,Bello 将责任推给了他和 Anjarwalla。Bello 告诉他们,如果交出政府要求的数据,他们就能获得自由。Gambaryan 失去耐心,反问 Bello:「你是希望我从右口袋拿出来,还是从左口袋拿出来?」他回忆自己站起来,夸张地从一个口袋里掏出东西,再从另一个口袋里掏出来。「我根本没有办法提供这些数据。」

数周过去了,谈判依然没有进展。斋月开始了,Gambaryan 每天清晨都会和 Anjarwalla 一起起床祷告,并在白天与他一起禁食,表示友好的团结。

然而,在经过近一个月的困境后,事情突然发生了变化。一天早晨,Gambaryan 醒来时看到 Anjarwalla 已经从清真寺回来,他去寻找同伴时,发现床上只剩下塞进枕头里的衬衫和袜子里的水瓶——Anjarwalla 逃跑了。

后来,Gambaryan 得知 Anjarwalla 设法搭乘航班逃离了尼日利亚。他推测,Anjarwalla 可能通过某种方式跳过了院子的围墙,成功避开了看守——那些看守早上常常在睡觉——然后付钱打车去机场,最后用他的第二本护照登上了飞机。

Gambaryan 已经意识到,自己在尼日利亚的处境即将发生剧变。他走到院子里,录了一段自拍视频,准备发给妻子 Yuki 和 Binance 的同事,边走边对着镜头说话。

「我已经被尼日利亚政府拘留了一个月,我不知道今天之后会发生什么。」他平静且控制地说道。「我没做错任何事。我一辈子都是警察。我只请求尼日利亚政府放我走,也请求美国政府提供帮助。我需要你们的帮助,大家。我不知道没有你们的帮助,我能不能脱身。请帮帮我。」

当尼日利亚方面得知 Anjarwalla 逃走后,守卫和看守人员拿走了 Gambaryan 的手机,开始疯狂搜查房子。很快,他们消失了,换上了新的人。

预感到接下来可能发生的更严重的事情,Gambaryan 设法说服一名尼日利亚人悄悄借给他手机,随后去浴室打电话给妻子,深夜联系到了 Yuki。Gambaryan 说,这是他们 17 年关系以来,第一次告诉她他感到害怕。Yuki 哭了,她走进衣柜里和他谈话,避免吵醒孩子。然后,Gambaryan 突然挂断了电话——有人来了。

一名军事官员告诉 Gambaryan 打包行李,说他将被释放。他虽然知道这不可能是真的,但还是打包了东西,走到外面的车里,看到 Ogunjobi 坐在车里。当 Gambaryan 问 Ogunjobi 他们要去哪里时,Ogunjobi 模糊地回答,或许他是要回家,但不是今天——然后默默地看着手机。

车子最终驶入了 EFCC 的院区,而不是停在总部附近,而是直接驶向了拘留设施。Gambaryan 愤怒地骂起看守们,已经不再在乎会冒犯到他们。

当他被带进 EFCC 的拘留楼时,他看到一群曾经在安全屋里看守他的人,现在也被关进了牢房,正接受调查,原因是他们可能允许 Anjarwalla 逃跑,甚至被怀疑与他有勾结。随后,Gambaryan 被单独关进了自己的牢房。

正如 Gambaryan 所描述的,那间牢房就像一个没有窗户的「盒子」,只有一个定时开关的冷水淋浴和一张不合时宜的 Posturepedic 床垫。房间里爬满了多达半打的蟑螂,大小不一。尽管阿布贾的高温让人喘不过气来,牢房里既没有空调,也没有通风,只有 Gambaryan 记得的「世界上最响的风扇」日夜运转。「我现在还可以听到那该死的风扇声音,」他说。

被单独关在那间牢房里,Gambaryan 说他开始与身体、环境以及这一切地狱般的处境产生了脱离感。第一晚,他甚至没有去想家人,脑袋一片空白,也没有注意到房间里的蟑螂。

到第二天早上,Gambaryan 已经超过 24 小时没有进食了。另一名被拘留者给了他一些饼干。他很快意识到,自己的生存依赖于 Ogunjobi,Ogunjobi 每隔几天会来给他送食物,有时还会让他用手机,在他短暂被释放出单独监禁时。很快,Gambaryan 以前的看守们也开始把家人送来的饭菜与他分享,而 Ogunjobi 来得次数越来越少,有时甚至拒绝让他使用手机。他曾在机场接过他的那位对 Gambaryan 工作充满崇拜的年轻人,似乎已经完全变了。「几乎可以说,他享受对我拥有控制权,」Gambaryan 说。

几天前还是他看守的尼日利亚人,现如今成了 Gambaryan 唯一的朋友。他教一名年轻的 EFCC 工作人员下国际象棋,他们在被关回牢房前的短暂空闲时常一起下棋。

被关进看守所几天后,Gambaryan 的律师来看了他,并告诉他,除了原本的逃税指控外,他现在还被指控洗钱。这些新指控意味着他可能面临 20 年的监禁。

在拘留中心的第二周,Gambaryan 的儿子满了 5 岁。生日那天,Gambaryan 被允许使用 EFCC 的电话给家人打电话,并抽了几根烟,其他时候这些都不允许。他和妻子通了 20 分钟的电话——他说妻子因焦虑而「崩溃」,然后和孩子们聊了会儿。儿子依然不明白他为什么不在家。Yuki 告诉 Gambaryan,儿子开始在不经意的时候为他哭泣,还经常到他们家里的办公室坐到他的椅子上。Gambaryan 解释给女儿听,说他还在和尼日利亚政府解决法律问题。后来他才知道,女儿在他被拘留的两周后,查了他的名字,看了新闻,知道的比她让他知道的要多。

除了偶尔和同监禁的囚犯见面,Gambaryan 还有两本书可以打发时间——一本是 EFCC 工作人员给他的丹·布朗小说,另一本是律师带来的《珀西·杰克逊》青少年小说。他几乎没有其他可以让自己忙碌的事情。他的思想在愤怒的诅咒、对自己的责备和一片空虚之间反复循环。

「这简直就是折磨,」Gambaryan 说。「我知道如果我一直待在那儿,我肯定会疯掉。」

尽管 Gambaryan 感到极度孤独,但他并没有被遗忘。当他在 EFCC 的牢房时,一群松散的朋友和支持者已经开始响应他在视频中发出的求救呼声。然而,很快他意识到,想要自由,真正的帮助并不会来自拜登政府。

在 Binance 内部,Gambaryan 发出的第一条关于自己被拘留的短信,立刻引发了无休止的危机应对会议,聘请律师和顾问,和任何在尼日利亚可能有影响力的政府官员联系。来自湾区的前美国检察官 Will Frentzen 曾处理过 Gambaryan 的许多大案子,在转入私人事务所 Morrison Foerster 工作后,接手了 Gambaryan 的案件,成为他的私人辩护律师。Gambaryan 的前同事 Patrick Hillman 曾和前佛罗里达州国会议员 Connie Mack 一起处理过危机应对工作,了解 Mack 处理人质事件的经验。Mack 同意为 Gambaryan 游说自己在立法界的联系人。Gambaryan 在 FBI 的老同事们也立即开始施压,要求 FBI 推动 Gambaryan 的释放。

然而,在美国政府的高层,一些支持 Gambaryan 的人表示,他们的求助遭到了谨慎的回应。「从 Gambaryan 被拘留的第一天起,国务院工作人员就一直努力确保他的安全、健康,并提供法律援助,并在他被刑事起诉后推动他的释放,」一位国务院高级官员在接受 WIRED 采访时表示,按部门政策他要求匿名。然而,根据参与此事的几位人士说法,拜登政府最初似乎对 Gambaryan 持一种模棱两可的态度。毕竟,Binance 刚刚同意向司法部支付巨额罚款,政府对整个加密货币行业的态度并不友好,Binance 的声誉也很差,「有毒」——正如 Gambaryan 的一位支持者所形容的那样。

「他们觉得或许尼日利亚方面确实有案件,」Frentzen 说。「他们不确定 Tigran 在那儿做了什么。所以他们都选择了退后。」

Gambaryan 恰好在一个极其危险的地缘政治时刻陷入了尼日利亚的困境。美国驻尼日利亚的大使在 2023 年退休,新任大使要到 2024 年 5 月才会正式上任。与此同时,尼日尔和乍得请求美国撤回驻两国的军队,因为这两个国家正在加强与俄罗斯的关系,而尼日利亚则是美国在该地区的关键军事盟友。这使得解救 Gambaryan 的谈判比与其他错误拘禁美国公民的国家(如俄罗斯或伊朗)更加复杂。「尼日利亚是唯一剩下的选项,他们也知道这一点,」Frentzen 说。「所以,时机真的很糟糕。Tigran 真的是这个世界上最不幸的人之一。」

当 Gambaryan 被关押在客房时,外交层面上可能会更加清楚地表明他是人质,前国会议员 Mack 表示,他曾为 Gambaryan 的释放进行游说。然而,对他提出的刑事指控使得局势变得复杂。「美国政府顺应了这个叙事,」Mack 说,「他们希望让法律程序自行展开。」

Frentzen 和他在 Morrison Foerster 的高级同事、前国家情报局总法律顾问 Robert Litt 表示,他们开始接触白宫,向他们解释 Gambaryan 面临的刑事案件多么薄弱。在尼日利亚检方提交的 300 多页「证据」中,只有两页提到了 Gambaryan 本人:一页是显示他在 Binance 工作的邮件;另一页是他的名片扫描件。

尽管如此,接下来的几个月里,美国政府依然没有干预 Gambaryan 的刑事起诉。对 Frentzen 来说,这是一种令人震惊的局面:一位在联邦政府工作多年的前 IRS 特工,曾处理过历史上许多重大的加密货币刑事案件和资产没收案件,却在这一看似是加密货币敲诈事件中,得到了政府仅仅是保持沉默的支持。

「这个人帮美国追回了数十亿美元,」Frentzen 回忆道,「而我们却无法把他从尼日利亚的困境中救出来?」

4 月初,Gambaryan 被带到法庭参加提审。他穿着一件黑色 T 恤和深绿色裤子,被公开展示,成为摧毁尼日利亚经济的邪恶力量的象征。当他坐在红色沙发椅上听取指控时,来自本地和国际的媒体蜂拥而至,摄像机有时离他的脸仅几英尺,他几乎无法掩饰自己的愤怒和屈辱。「我感觉自己像个马戏团的动物,」他说。

在这次庭审中、接下来的一次庭审中以及随后的法庭文件中,检察官辩称,如果让 Gambaryan 保释,他很可能会逃跑,并以 Anjarwalla 的逃脱为例。他们奇怪地强调,Gambaryan 出生在亚美尼亚,尽管他 9 岁时就随家人离开了那个国家。更荒唐的是,他们声称 Gambaryan 和 EFCC 拘留所的其他囚犯策划了一个阴谋,打算用某个替身代替自己逃跑,而 Gambaryan 则表示这完全是一个荒谬的谎言。

有一次,检察官明确表示,拘押 Gambaryan 对尼日利亚政府来说至关重要,是他们对 Binance 施压的杠杆。「第一被告 Binance 是虚拟运营的,」检察官告诉法官,「我们唯一能抓住的,就是这个被告。」

法官拒绝裁定 Gambaryan 的保释,决定继续将他拘押。经过两周的单独监禁后,他被转移到真正的监狱——库杰监狱。

警卫们——包括一贯的 Ogunjobi——将 Gambaryan 带上了一辆面包车。Ogunjobi 把香烟还给了他,他在从阿布贾市中心出发的一个小时车程中几乎一直在吸烟,途中他们穿过了一个看起来像是城市郊区贫民窟的地方。在这段旅程中,Gambaryan 被允许打电话给 Yuki 和一些 Binance 的高管,其中一些人已经有几周没有听到他的消息。

这段开往库杰监狱的旅程,途中经过了以极差的条件和曾关押博科圣地嫌疑犯而闻名的监狱,Gambaryan 表示他感到麻木,「与外界隔绝」,对自己的命运完全放弃了控制。「我就一小时、一分钟地活着,」他说。

当他们抵达并穿过监狱的大门时,Gambaryan 第一次看到了监狱那低矮的建筑,墙面涂成浅黄色,许多建筑仍然被 ISIS 的袭击摧毁,几乎两年前的一次袭击让超过 800 名囚犯逃脱。Gambaryan 的 EFCC 看守将他带进监狱,并带到监狱长的办公室。后来他得知,监狱长是根据国家安全顾问 Ribadu 的指示,对他进行严密监控。

随后,Gambaryan 被带到了「隔离区」,一个专门为高风险囚犯和愿意支付额外费用以获得特殊待遇的 VIP 囚犯设立的单元。这个 6×10 英尺的房间里有一个厕所、一张金属床架,上面放着 Gambaryan 所说的「简单毯子」作为床垫,还有一扇带金属栏杆的窗户。与 EFCC 地牢相比,这个房间算是一个「升级版」:他有了阳光和新鲜空气——虽然被几百米外的垃圾火堆污染了——还能看到树木,每到晚上这些树上就会成群结队地飞来蝙蝠。

Gambaryan 在监狱的第一个晚上,下起了雨,窗户吹进来一阵凉风。「虽然环境很差,」Gambaryan 说,「但我觉得自己仿佛在天堂。」

不久后,Gambaryan 结识了他的邻居。其中一位是尼日利亚副总统的堂兄,另一位是涉嫌诈骗并等待美国引渡的嫌犯,涉案金额高达 1 亿美元;第三位是尼日利亚前副警察局长 Abba Kyari,他因涉嫌受贿而被美国起诉,尽管尼日利亚拒绝了美国的引渡请求。Gambaryan 认为,Kyari 的案件更多是因为他得罪了一些腐败的尼日利亚官员。

Gambaryan 表示,Kyari 在监狱里有很大的影响力,其他囚犯基本上都为他工作。Kyari 的妻子会给大家带来家常饭,甚至连警卫也不例外。Gambaryan 尤其喜欢 Kyari 妻子做的某种来自尼日利亚北部的饺子,她会为他做额外的。他则会和 Kyari 分享律师从快餐店 Kilimanjaro 带来的外卖,Kyari 特别喜欢他们的苏格兰蛋。

Gambaryan 的邻居们教会了他监狱生活的潜规则:如何获得手机,如何避免与监狱工作人员发生冲突,以及如何避免其他囚犯的暴力。Gambaryan 坚称,他从未向警卫行贿——尽管他们有时会要求几万美元的天文数字——但由于与 Kyari 关系密切,他仍然得到了保护。「他就像我的 Red,」Gambaryan 说,把 Kyari 比作《肖申克的救赎》中 Morgan Freeman 扮演的角色。「他是我能活下来的关键。」

接下来的几周里,Gambaryan 的案件继续进行,他被定期送回阿布贾参加听证会,每次听证会中,法官似乎总是偏向检察官。5 月 17 日——他的 40 岁生日——他再次参加了听证会,最终他的保释请求被拒绝。当天晚上,律师们带来了由 Binance 支付的大蛋糕,送到了库杰监狱,他和邻居们以及警卫们一起分享了这块蛋糕。

每天晚上,Gambaryan 都会被早早锁进牢房,通常是从晚上 7 点开始,甚至比其他囚犯早好几个小时,而他一直被一名警卫盯着,警卫会在本子上记录他的每个动作,所有这一切都是根据国家安全顾问的命令进行的。他发现自己可以在隔离区庭院入口的窗台上做引体向上,借此锻炼身体。尽管牢房里有巨大的蟑螂、壁虎,甚至蝎子——他学会了每次穿鞋前把鞋里抖出来的小米色蝎子——但他还是慢慢适应了监狱生活。

有时候,他会从梦中醒来,梦见自己还在外面,突然意识到自己在这个又小又脏的牢房里,然后他会从床上爬起来,焦虑地在狭小的空间里踱步,直到早上 6 点左右警卫才让他出去。不过,最终 Gambaryan 表示,他的梦境也变得充满了监狱的影像。

五月的一个下午,Gambaryan 在和律师会面时开始感到不适。他回到牢房,躺下后,接下来的整个晚上他都在呕吐。他猜自己可能是食物中毒,但警卫做了血液检查,结果显示他得了疟疾。警卫要求他支付现金,拿这些钱买了点滴液体,挂在牢房墙上的钉子上,还给他打了抗疟疾的针。

第二天早晨,Gambaryan 有一个法庭听证会,他告诉警卫自己太虚弱,连走路都做不到,但他们还是把点滴拔掉,强行将他送上了车,称这是执行官方命令。到达法院时,他勉强爬上了长长的台阶,但一进法庭,他的视线开始模糊,房间开始旋转。接下来,他就跪倒在地。警卫帮他站起来,他瘫坐在椅子上,律师们要求法庭下令将他送往医院。

法官发出了住院命令,但 Gambaryan 并没有直接被送往医疗机构,而是被送回了库杰监狱,法院、他的律师、监狱、国家安全顾问办公室和美国国务院都在讨论是否暂时释放他,因为他们担心他有逃脱风险。在接下来的 10 天里,Gambaryan 躺在牢房里,无法进食,也无法站起来。最终,他被送到位于阿布贾的尼扎米耶医院,做了胸部 X 光检查,简单检查后开了抗生素,医生说他没事,随后却没有任何解释地将他送回了库杰监狱。

事实上,Gambaryan 的病情比之前更加严重。他的朋友、土耳其裔加拿大人 Chagri Poyraz 最终不得不飞到安卡拉,向土耳其政府查询 Gambaryan 的医院记录,才得知他的 X 光显示他患有多种严重的细菌性肺部感染。几个月后,案件中的法官也要求库杰监狱的医疗主任 Abraham Ehizojie 出庭,解释为什么没有遵循住院命令。检察官拿出了 Gambaryan 的医疗记录,称他拒绝治疗,并要求被送回监狱,但 Gambaryan 对此表示坚决否认。

回到库杰监狱的牢房后,Gambaryan 连续几天高烧不退,体温达到 104 华氏度。在短暂的住院期间,警卫搜查了他的牢房,发现了他藏着的手机,因此他被彻底隔离,无法与外界联系,直到他的邻居帮他弄到了一部新手机。他的身体越来越虚弱,呼吸也变得困难,体温一直没有退下。Gambaryan 逐渐感到自己可能活不成了。有一段时间,他给 Will Frentzen 打了电话,告诉他自己可能已经是病危状态了。然而,库杰监狱的官员仍然拒绝将他送回医院。

尽管如此,Gambaryan 并没有死去。但他在床上躺了近一个月,直到终于能够站起来、重新进食。他的体重比入狱时减少了将近 30 磅。

有一天,当他在牢房里恢复时,警卫告诉他有客人来探望他。虽然他还感到虚弱,但他仍然慢慢地走到监狱前面的办公室。进门后,他看到的是美国国会的两位议员——弗朗西·希尔(French Hill)和克里西·霍拉汉(Chrissy Houlahan),分别来自两个党派。Gambaryan 几乎不敢相信他们是真的——这是几个月来他见到的第一批美国人,除了偶尔探望他的美国国务院低级别官员。

接下来的 25 分钟里,他们聆听了 Gambaryan 描述监狱的恶劣条件,以及他与疟疾和后来的肺炎之间生死一线的经历。希尔回忆说,Gambaryan 说话声音非常轻,以至于两位议员不得不靠前才能听清他讲的内容,尤其是在风扇的噪音下。

有时,Gambaryan 的眼睛会充满泪水,因为孤独的痛苦和濒临死亡的恐惧终于让他情不自禁。「他看起来像一个生病、虚弱、情绪崩溃的人,真的是需要一个拥抱。」希尔说。两位议员分别给了他一个拥抱,并表示他们会为他的释放而努力。

然后,他被带回了牢房。

第二天,6 月 20 日,希尔和霍拉汉在阿布贾机场的停机坪上录制了一段视频。「我们已经请求我们的使馆推动 Tigran 的人道主义释放,考虑到监狱的恶劣条件、他的清白以及他的健康状况,」希尔对着镜头说。「我们希望他能回家,剩下的就让 Binance 和尼日利亚人自己去处理。」

Connie Mack 与他老朋友们的谈话产生了效果:在一次关于美国公民被外国政府拘留的子委员会听证会上,Gambaryan 的乔治亚州议员 Rich McCormick 提出,应该将 Gambaryan 的案件视为被外国政府扣押的人质案件。他引用了《莱文森法案》,该法案要求美国政府协助被错误拘禁的公民。「美国的外交干预是否必需才能确保释放被拘留者?绝对是的,绝对是的。」McCormick 在听证会上说。「这个人应该得到更好的待遇。」

与此同时,16 名共和党议员签署了一封信,要求白宫将 Gambaryan 的案件当作人质案件处理。几周后,McCormick 将这一要求作为议会决议提了出来。超过一百名前联邦特工和检察官也签署了另一封信,要求国务院加强努力,帮助解决这个问题。

根据多位消息来源,FBI 局长克里斯托弗·雷(Christopher Wray)在 6 月访问尼日利亚时与总统廷努布会面时提到了 Gambaryan 的案件。此后,尼日利亚税务机关 FIRS 撤销了对 Gambaryan 的逃税指控。然而,由 EFCC 提出的更严重的洗钱指控依然存在,并且仍然威胁着他长达数十年的监禁。

几个月来,Gambaryan 的支持者们一直希望尼日利亚能够最终与 Binance 达成协议,结束对他的起诉。然而,Binance 的代表表示,到那时,他们似乎无法提出令尼日利亚方面感兴趣的条件,尼日利亚方面甚至不再暗示会接受任何付款。每当他们感觉快要接近达成协议时,要求就会发生变化,相关官员会消失,协议也随之破裂。「就像露西和足球的故事一样,」Arnold & Porter 律师事务所的律师、前 CIA 副总法律顾问 Deborah Curtis 说道,她当时在为 Binance 提供法律服务。

随着夏天的过去,Gambaryan 的支持者们开始认为,尼日利亚和 Binance 之间的谈判已经陷入死胡同,刑事案件进展得足够远,单靠 Binance 无法让 Gambaryan 获得自由。「这开始变得清晰,」Frentzen 说道,「这件事只能通过美国政府来解决——否则就没有希望了。」

与此同时,Gambaryan 的健康状况再次恶化。长时间躺在金属床架上,加重了他十多年前在 IRS-CI 训练时受的旧背伤,后来被诊断为椎间盘突出——脊椎间的软组织外层破裂,导致内层的软垫突出,压迫神经并引发剧烈的持续性疼痛。

到 8 月,Gambaryan 通过短信告诉我,他「几乎已经瘫痪」。他已经好几周没下床了,因缺乏运动,他还在服用血液稀释剂以防止腿部血栓。他写道,每晚他都会因疼痛过于严重,无法入睡,通常直到早上五六点才会昏昏欲睡,甚至无法看书。偶尔,他会给家人打电话,与女儿聊聊天,听她玩一款叫《Omori》的日本角色扮演游戏,那是他为她装的电脑,直到她在亚特兰大睡觉。然后,几个小时后,他才会昏睡过去。

尽管国会成员的到访和越来越多的呼声要求释放他,Gambaryan 似乎几乎陷入了绝望,正处于他在监狱中的最低谷。

「我尽量在 Yuki 和孩子们面前装作坚强,但情况真的很糟糕,」他写给我。「我现在真的处于一个黑暗的地方。」

几天后,一段视频出现在 X 平台,视频中 Gambaryan 借着拐杖一瘸一拐地走进法庭,拖着一只脚。在视频中,他向走廊上的一名警卫求助,但警卫甚至拒绝了他的请求。Gambaryan 后来告诉我,法庭工作人员接到指示,不允许提供任何帮助,也不让他使用轮椅,担心这样会引发公众的同情。

「这真是太他妈糟糕了!为什么我不能用轮椅?」Gambaryan 在视频中愤怒地喊道。「我可是个无辜的人!」

「我他妈是人啊!」Gambaryan 继续说,声音几乎哽咽。他艰难地用拐杖迈出几步,摇头表示不敢相信,之后靠在墙上休息。「我根本不行。」

如果当时的指令是为了阻止 Gambaryan 在进入法庭时引发同情,那么这一做法完全适得其反。视频在网上迅速传播,并被观看了数百万次。

到了 2024 年秋季,美国政府似乎终于达成共识,认为是时候让 Gambaryan 回家了。9 月,众议院外交事务委员会通过了一项两党决议,批准了 McCormick 提出的议案,要求优先处理 Gambaryan 的案件。「我敦促国务院,我敦促拜登总统:对尼日利亚政府施加更大压力,」议员 Hill 在听证会上说道。「必须认识到,一个美国公民被一个友好的国家绑架并关押,完全与他无关。」

Gambaryan 的一些支持者透露,他们听说新任驻尼日利亚大使也开始频繁向尼日利亚官员,甚至总统廷努布提起 Gambaryan 的情况,以至于至少有一位部长在 WhatsApp 上屏蔽了大使。

在 9 月下旬的联合国大会期间,美国驻联合国大使在与尼日利亚外长会晤时提到 Gambaryan 的案件,并强调需要立即释放他,会议记录中如此写道。与此同时,Binance 雇佣了一辆带有数字广告牌的卡车,在联合国和曼哈顿中城周围行驶,展示 Gambaryan 的面容,并呼吁尼日利亚停止非法监禁他。

与此同时,白宫国家安全顾问 Jake Sullivan 与尼日利亚国家安全顾问努胡·里巴杜通了电话,基本上要求释放 Gambaryan,多位参与推动 Gambaryan 释放的消息人士表示。最具影响力的消息之一是,几位支持者表示,美国官员明确表示,Gambaryan 的案件将成为拜登总统与尼日利亚总统廷努布在联合国大会或其他场合会谈的障碍,这一消息深深困扰了尼日利亚方面。

尽管所有这些施加的压力,是否释放 Gambaryan 的决定依然掌握在尼日利亚政府手中。「有一段时间,尼日利亚方面意识到这是一个非常糟糕的决定,」一位不愿透露姓名的 Gambaryan 支持者说道,由于谈判的敏感性,他要求匿名。「之后,问题就变成了他们是屈服,还是因为自尊心,或者因为已经无法回头而坚持下去。」

在 10 月的某一天,在从库杰(Kuje)到阿布贾(Abuja)法庭的漫长车程中——到那时,Gambaryan 已经数不清自己经历了多少次庭审——司机接到了一个电话。他通话了一会儿,然后转过车头,带着 Gambaryan 回到了监狱。到监狱后,他被带到前台,告诉他因为身体不适,不能去法庭。那是一种陈述,而非询问。

回到牢房后,Gambaryan 打电话给 Will Frentzen,Frentzen 告诉他,这可能意味着他们终于准备好将他送回家了。经历了过去八个月多次破灭的希望,Gambaryan 并没有轻易相信这一消息。

几天后,法院举行了庭审,但 Gambaryan 并未出席,检方告诉法官,他们因为 Gambaryan 的健康状况,决定撤销对他的所有指控。库杰监狱的官员花了一整天时间处理文件,然后把他带出牢房,给他拿来了他去阿布贾时带的行李箱,并将他送到了阿布贾大陆酒店(Abuja Continental Hotel)。Binance 为他预定了一个房间,并安排了私人保安守卫,还请来了一位医生为他检查身体,确保他足够健康,能乘飞机。对 Gambaryan 来说,这一切来得太过突然,经历了这么多个月的无望等待,这一切几乎让人难以相信。

第二天,在阿布贾机场的跑道上,尼日利亚官员把他的护照还给了他——虽然他们先是就他因签证过期被罚款 2000 美元发生了一番争执。美国国务院的工作人员帮助他从轮椅上站起来,登上了装备有医疗设备的私人飞机。Gambaryan 并不知道,Binance 的工作人员已经为这架航班筹备了好几周——尼日利亚官员曾经告诉他们 Gambaryan 会被释放,但又反悔——他们甚至为他安排了飞越尼日尔(Niger)上空的航线,尼日尔官员在起飞前不到一小时才签署了同意书。

在飞机上,Gambaryan 吃了几口沙拉,躺在沙发上睡着了,醒来时已经到了罗马。

Binance 安排了司机和私人保安在意大利机场接他,并带他到机场酒店过夜,第二天再飞回亚特兰大。在酒店里,他打电话给 Yuki,然后给 Ogunjobi 打了电话——他在尼日利亚的前朋友,也是几个月前劝他回阿布贾的人。

Gambaryan 说,他想听 Ogunjobi 怎么解释自己。当他打电话时,Ogunjobi 在电话里开始哭泣,一再道歉,并感谢上帝,Gambaryan 终于被释放。

这一切让 Gambaryan 难以承受,他静静地听着,却没有接受对方的道歉。就在 Ogunjobi 倾诉的同时,他注意到一位美国朋友打来了电话,是他曾合作过的特勤局特工。Gambaryan 那时还不知道,这位特工刚好在罗马参加一个会议,和他以前的老板——IRS-CI 网络犯罪部门负责人 Jarod Koopman 一起,他们打算为他带来啤酒和比萨。

Gambaryan 告诉 Ogunjobi 他得挂断电话,然后结束了通话。

12 月的一个寒冷多风的日子,前联邦特工、检察官、国务院官员和国会助手们聚集在 Rayburn House 办公楼的一个豪华房间里交谈。国会议员们一个接一个走进来,和穿着深蓝色西装和领带、胡须修剪整齐、头发剃光的 Tigran Gambaryan 握手。尽管他因一个月前在乔治亚州做的紧急脊椎手术而稍微跛行,但他的步伐仍然坚定。

Gambaryan 和每一位立法者、助手、国务院官员合影,并与他们交谈,感谢他们为他的回家所做的努力。当法国议员 Hill 说再次见到他很高兴时,Gambaryan 打趣地说,他希望这次见面,他的气味比在库杰时更好。

这场接待只是 Gambaryan 回国后获得的一系列 VIP 欢迎之一。在乔治亚州的机场,McCormick 议员前来迎接,并送给他一面前一天在国会大厦上空飘扬的美国国旗。白宫也发布了声明,称总统拜登已致电尼日利亚总统,感谢总统 Tinubu 在基于人道主义原因下促成了 Gambaryan 的释放。

后来我得知,这份感谢声明是美国政府与尼日利亚达成协议的一部分,其中还包括协助尼日利亚对 Binance 的调查——这一调查至今仍在进行。尼日利亚继续缺席起诉 Binance 和 Anjarwalla。Binance 的发言人在声明中表示,公司「感到宽慰和感激」,Gambaryan 已顺利回家,并感谢所有为其释放付出努力的人。「我们迫切希望将这一事件放在过去,继续为尼日利亚及全球区块链行业的美好未来而努力,」声明中写道。「我们将继续捍卫自己,反对那些毫无根据的指控。」 尼日利亚政府官员未回应 WIRED 关于 Gambaryan 案件的多次采访请求。

接待会结束后,Gambaryan 和我一起打车离开,我问他接下来打算做什么。他说,如果新政府愿意接纳他,他可能会重新回到政府工作——当然,也要看 Yuki 是否愿意再次接受搬回华盛顿的生活。加密货币新闻网站 Coindesk 上个月报道称,他已被一些与特朗普总统有联系的加密行业人士推荐担任 SEC 的加密资产负责人或 FBI 网络部门的高级职位。考虑这些之前,他模糊地说:「我可能需要一些时间来理清思绪。」

我问他,尼日利亚的经历让他有什么变化。他用一种奇怪的轻松语气回答:「我猜,它确实让我更愤怒了吧?」他似乎在第一次思考这个问题。「它让我想要报复那些对我做这件事的人。」

对 Gambaryan 来说,复仇可能不只是幻想。他正在对尼日利亚政府提起人权诉讼,这个案件始于他被拘留时,他希望能够调查那些他认为将他当人质囚禁了大半年的尼日利亚官员。他说,有时他甚至会给那些他认为应对事件负责的官员发信息,告诉他们:「你们会再见到我。」他说他们的所作所为「让徽章蒙羞」,他能原谅他们对自己做的事,但不能原谅他们对自己家人所做的事。

「我这么做傻吗?可能吧,」他在出租车里告诉我。「当时我背部剧痛,躺在地板上,实在是太无聊了。」

当我们走出车子,来到他在阿灵顿的酒店时,Gambaryan 点燃了一支香烟,我告诉他,尽管他自己说比入狱前更愤怒,但在我看来,他似乎比过去几年更冷静、也更快乐——我记得曾报道他连续打击腐败联邦特工、加密货币洗钱犯和虐待儿童者时,他总给我一种愤怒、充满动力、不懈追踪调查目标的印象。

Gambaryan 回应说,如果他现在显得更加放松,那只是因为他终于回到家了——他很感激能见到家人和朋友,能再次走路,能摆脱那些比他自己还要庞大的力量之间的冲突,这些冲突与他毫无关系。能活着走出监狱,没死在那里。

至于过去那种愤怒的驱动,Gambaryan 则不同意。

「我不确定那是愤怒。」他说,「那是正义。我想要的是正义,而我现在仍然如此。」

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。