在以太坊协议设计中,约一半的内容涉及不同类型的 EVM 改进,其余部分则由各种小众主题构成,这就是「繁荣」的意义所在。

原文标题:《Possible futures of the Ethereum protocol, part 6: The Splurge》

撰文:Vitalik Buterin

编译:zhouzhou,BlockBeats

以下为原文内容(为便于阅读理解,原内容有所整编):

有些事物很难归入单一类别,在以太坊协议设计中,有许多「细节」对以太坊的成功非常重要。实际上,约一半的内容涉及不同类型的 EVM 改进,其余部分则由各种小众主题构成,这就是「繁荣」的意义所在。

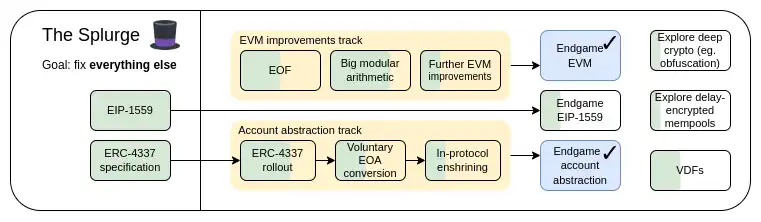

2023 年路线图:繁荣

繁荣:关键目标

- 将 EVM 变为高性能和稳定的「最终状态」

- 将账户抽象引入协议,允许所有用户享受更安全和便捷的账户

- 优化交易费用经济,提高可扩展性同时降低风险

- 探索先进的密码学,使以太坊在长期内显著改善

EVM 改进

解决了什么问题?

目前的 EVM 难以进行静态分析,这使得创建高效实现、正式验证代码和进行进一步扩展变得困难。此外,EVM 的效率较低,难以实现许多形式的高级密码学,除非通过预编译显式支持。

它是什么,如何运作?

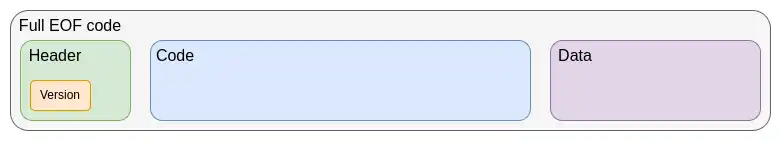

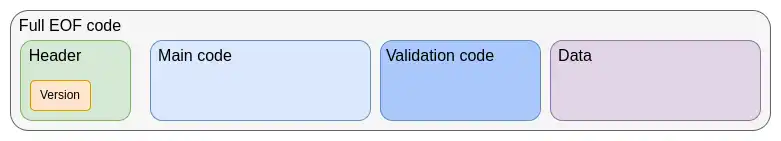

当前 EVM 改进路线图的第一步是 EVM 对象格式(EOF),计划在下一个硬分叉中纳入。EOF 是一系列 EIP,指定了一个新的 EVM 代码版本,具有许多独特的特征,最显著的是:

- 代码(可执行,但无法从 EVM 中读取)与数据(可读取,但无法执行)之间的分离

- 禁止动态跳转,仅允许静态跳转

- EVM 代码无法再观察与燃料相关的信息

- 添加了一种新的显式子例程机制

EOF 代码的结构

繁荣:EVM 改进(续)

旧式合约将继续存在并可创建,尽管最终可能会逐步弃用旧式合约(甚至可能强制转换为 EOF 代码)。新式合约将受益于 EOF 带来的效率提升——首先是通过子例程特性稍微缩小的字节码,随后则是 EOF 特定的新功能或减少的 gas 成本。

在引入 EOF 后,进一步的升级变得更加容易,目前发展最完善的是 EVM 模块算术扩展(EVM-MAX)。EVM-MAX 创建了一组专门针对模运算的新操作,并将其放置在一个无法通过其他操作码访问的新内存空间中,这使得使用诸如 Montgomery 乘法等优化成为可能。

一个较新的想法是将 EVM-MAX 与单指令多数据(SIMD)特性结合,SIMD 作为以太坊的一个理念已经存在很长时间,最早由 Greg Colvin 的 EIP-616 提出。SIMD 可用于加速许多形式的密码学,包括哈希函数、32 位 STARKs 和基于格的密码学,EVM-MAX 和 SIMD 的结合使得这两种性能导向的扩展成为自然的配对。

一个组合 EIP 的大致设计将以 EIP-6690 为起点,然后:

- 允许 (i) 任何奇数或 (ii) 任何最高为 2768 的 2 的幂作为模数

- 对于每个 EVM-MAX 操作码(加法、减法、乘法),添加一个版本,该版本不再使用 3 个立即数 x、y、z,而是使用 7 个立即数:x_start、x_skip、y_start、y_skip、z_start、z_skip、count。在 Python 代码中,这些操作码的作用类似于:

for i in range(count):

mem[z_start + z_skip * count] = op(

mem[x_start + x_skip * count],

mem[y_start + y_skip * count]

)

实际实现中,这将以并行方式处理。

- 可能添加 XOR、AND、OR、NOT 和 SHIFT(包括循环和非循环),至少对于 2 的幂模数。同时添加 ISZERO(将输出推送到 EVM 主堆栈),这将足够强大以实现椭圆曲线密码学、小域密码学(如 Poseidon、Circle STARKs)、传统哈希函数(如 SHA256、KECCAK、BLAKE)和基于格的密码学。其他 EVM 升级也可能实现,但迄今为止关注度较低。

现有研究链接

- EOF: https://evmobjectformat.org/

- EVM-MAX: https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-6690

- SIMD: https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-616

剩下的工作及权衡

目前,EOF 计划在下一个硬分叉中纳入。尽管总是有可能在最后一刻移除它——之前的硬分叉中曾有功能被临时移除,但这样做将面临很大挑战。移除 EOF 意味着未来对 EVM 的任何升级都需在没有 EOF 的情况下进行,虽然可以做到,但可能更困难。

EVM 的主要权衡在于 L1 复杂性与基础设施复杂性,EOF 是需要添加到 EVM 实现中的大量代码,静态代码检查也相对复杂。然而,作为交换,我们可以简化高级语言、简化 EVM 实现以及其他好处。可以说,优先考虑以太坊 L1 持续改进的路线图应包括并建立在 EOF 之上。

需要做的一项重要工作是实现类似 EVM-MAX 加 SIMD 的功能,并对各种加密操作的 gas 消耗进行基准测试。

如何与路线图的其他部分交互?

L1 调整其 EVM 使得 L2 也能更容易地进行相应调整,如果二者不进行同步调整,可能会造成不兼容,带来不利影响。此外,EVM-MAX 和 SIMD 可以降低许多证明系统的 gas 成本,从而使 L2 更加高效。它还使得通过用可以执行相同任务的 EVM 代码替代更多的预编译变得更加容易,可能不会大幅影响效率。

账户抽象

解决了什么问题?

目前,交易只能通过一种方式进行验证:ECDSA 签名。最初,账户抽象旨在超越这一点,允许账户的验证逻辑为任意的 EVM 代码。这可以启用一系列应用:

- 切换到抗量子密码学

- 轮换旧密钥(广泛被认为是推荐的安全实践)

- 多重签名钱包和社交恢复钱包

- 使用一个密钥进行低价值操作,使用另一个密钥(或一组密钥)进行高价值操作

允许隐私协议在没有中继的情况下工作,显著降低其复杂性,并消除一个关键的中央依赖点

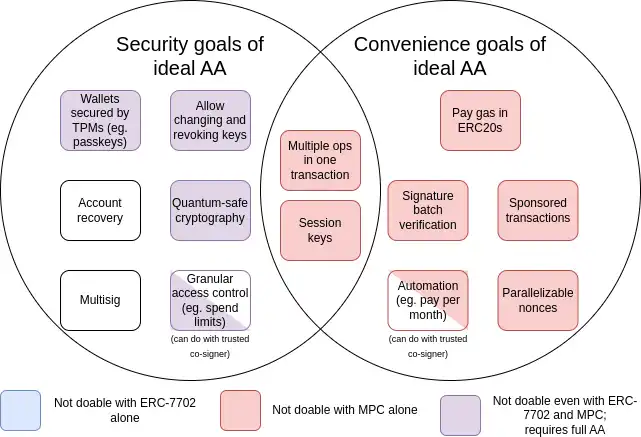

自 2015 年账户抽象提出以来,其目标也扩展到了包括大量「便利目标」,例如,某个没有 ETH 但拥有一些 ERC20 的账户能够用 ERC20 支付 gas。以下是这些目标的汇总图表:

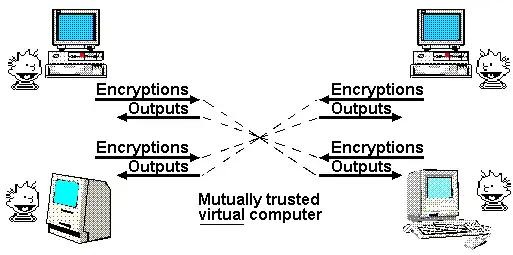

MPC(多方计算)是一种已有 40 年历史的技术,用于将密钥分成多个部分并存储在多个设备上,利用密码学技术生成签名,而无需直接组合这些密钥部分。

EIP-7702 是计划在下一个硬分叉中引入的一项提案,EIP-7702 是对提供账户抽象便利性以惠及所有用户(包括 EOA 用户)的日益认识的结果,旨在在短期内改善所有用户的体验,并避免分裂成两个生态系统。

该工作始于 EIP-3074,并最终形成 EIP-7702。EIP-7702 将账户抽象的「便利功能」提供给所有用户,包括今天的 EOA(外部拥有账户,即受 ECDSA 签名控制的账户)。

从图表中可以看到,虽然一些挑战(尤其是「便利性」挑战)可以通过渐进技术如多方计算或 EIP-7702 解决,但最初提出账户抽象提案的主要安全目标只能通过回溯并解决原始问题来实现:允许智能合约代码控制交易验证。迄今为止尚未实现的原因在于安全地实施,这一点是一项挑战。

它是什么,如何运作?

账户抽象的核心是简单的:允许智能合约发起交易,而不仅仅是 EOA。整个复杂性来自于以一种对维护去中心化网络友好的方式实现这一点,并防范拒绝服务攻击。

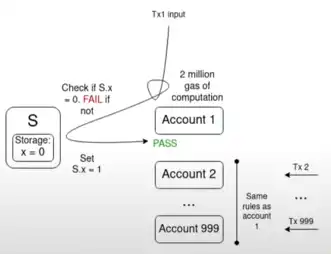

一个典型的关键挑战是多重失效问题:

如果有 1000 个账户的验证函数都依赖于某个单一值 S,并且当前值 S 使得内存池中的交易都是有效的,那么有一个单一交易翻转 S 的值可能会使内存池中的所有其他交易失效。这使得攻击者能够以极低的成本向内存池发送垃圾交易,从而堵塞网络节点的资源。

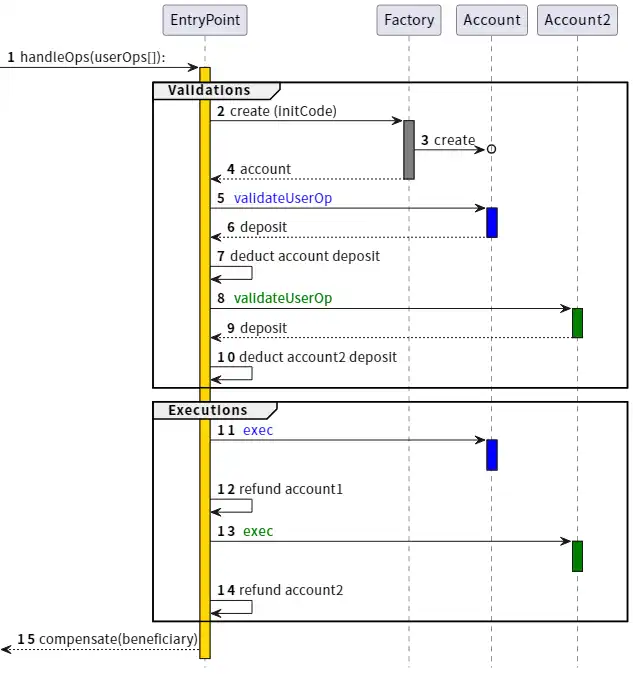

经过多年的努力,旨在扩展功能的同时限制拒绝服务(DoS)风险,最终得出了实现「理想账户抽象」的解决方案:ERC-4337。

ERC-4337 的工作原理是将用户操作的处理分为两个阶段:验证和执行。所有验证首先被处理,所有执行随后被处理。在内存池中,只有当用户操作的验证阶段只涉及其自身账户并且不读取环境变量时,才会被接受。这可以防止多重失效攻击。此外,对验证步骤也强制实施严格的 gas 限制。

ERC-4337 被设计为一种额外协议标准(ERC),因为在当时以太坊客户端开发者专注于合并(Merge),没有额外的精力来处理其他功能。这就是为什么 ERC-4337 使用了名为用户操作的对象,而不是常规交易。然而,最近我们意识到需要将其中至少部分内容写入协议中。

两个关键原因如下:

- EntryPoint 作为合约的固有低效性:每个捆绑约有 100,000 gas 的固定开销,以及每个用户操作额外的数千 gas。

- 确保以太坊属性的必要性:如包含列表所创建的包含保证需要转移到账户抽象用户。

此外,ERC-4337 还扩展了两个功能:

- 支付代理(Paymasters):允许一个账户代表另一个账户支付费用的功能,这违反了验证阶段只能访问发送者账户本身的规则,因此引入了特殊处理以确保支付代理机制的安全性。

- 聚合器(Aggregators):支持签名聚合的功能,如 BLS 聚合或基于 SNARK 的聚合。这对于在 Rollup 上实现最高的数据效率是必要的。

现有研究链接

- 关于账户抽象历史的演讲:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iLf8qpOmxQc

- ERC-4337:https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-4337

- EIP-7702:https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-7702

- BLSWallet 代码(使用聚合功能):https://github.com/getwax/bls-wallet

- EIP-7562(写入协议的账户抽象):https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-7562

- EIP-7701(基于 EOF 的写入协议账户抽象):https://eips.ethereum.org/EIPS/eip-7701

剩下的工作及权衡

目前主要需要解决的是如何将账户抽象完全引入协议,最近受到欢迎的写入协议账户抽象 EIP 是 EIP-7701,该提案在 EOF 之上实现账户抽象。一个账户可以拥有一个单独的代码部分用于验证,如果账户设置了该代码部分,则该代码将在来自该账户的交易的验证步骤中执行。

这种方法的迷人之处在于,它清晰地表明了本地账户抽象的两种等效视角:

- 将 EIP-4337 作为协议的一部分

- 一种新的 EOA 类型,其中签名算法为 EVM 代码执行

如果我们从对验证期间可执行代码复杂性设定严格界限开始——不允许访问外部状态,甚至在初期设定的 gas 限制也低到对量子抗性或隐私保护应用无效——那么这种方法的安全性就非常明确:只是将 ECDSA 验证替换为需要相似时间的 EVM 代码执行。

然而,随着时间的推移,我们需要放宽这些界限,因为允许隐私保护应用在没有中继的情况下工作,以及量子抗性都是非常重要的。为此,我们需要找到更灵活地解决拒绝服务(DoS)风险的方法,而不要求验证步骤必须极度简约。

主要的权衡似乎是「快速写入一种让较少人满意的方案」与「等待更长时间,可能获得更理想的解决方案」,理想的方法可能是某种混合方法。一种混合方法是更快地写入一些用例,并留出更多时间来探索其他用例。另一种方法是在 L2 上首先部署更雄心勃勃的账户抽象版本。然而,这面临的挑战是,L2 团队需要对采用提案的工作充满信心,才能愿意进行实施,尤其是要确保 L1 和 / 或其他 L2 未来能够采用兼容的方案。

我们还需要明确考虑的另一个应用是密钥存储账户,这些账户在 L1 或专用 L2 上存储账户相关状态,但可以在 L1 和任何兼容的 L2 上使用。有效地做到这一点可能要求 L2 支持诸如 L1SLOAD 或 REMOTESTATICCALL 的操作码,但这也需要 L2 上的账户抽象实现支持这些操作。

它如何与路线图的其他部分互动?

包含列表需要支持账户抽象交易,在实践中,包含列表的需求与去中心化内存池的需求实际上非常相似,尽管对于包含列表来说灵活性稍大。此外,账户抽象实现应该尽可能在 L1 和 L2 之间实现协调。如果将来我们期望大多数用户使用密钥存储 Rollup,账户抽象设计应以此为基础。

EIP-1559 改进

它解决了什么问题?

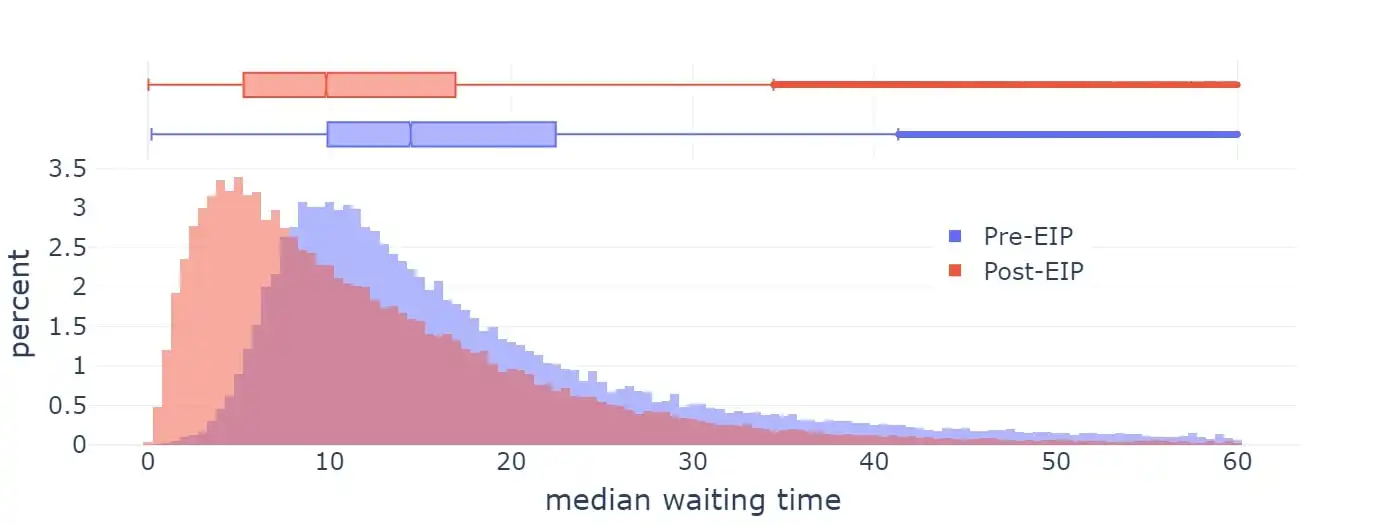

EIP-1559 于 2021 年在以太坊上激活,显著改善了平均区块包含时间。

等待时间

然而,当前 EIP-1559 的实施在多个方面并不完美:

- 公式略有缺陷:它并不是以 50% 的区块为目标,而是针对约 50-53% 的满区块,这取决于方差(这与数学家所称的「算术 - 几何均值不等式」有关)。

- 在极端情况下调整不够迅速。

后面用于 blobs 的公式(EIP-4844)是专门设计来解决第一个问题的,整体上也更简洁。然而,EIP-1559 本身以及 EIP-4844 都未尝试解决第二个问题。因此,现状是一个混乱的中间状态,涉及两种不同的机制,并且有一种观点认为,随着时间的推移,两者都需要进行改进。

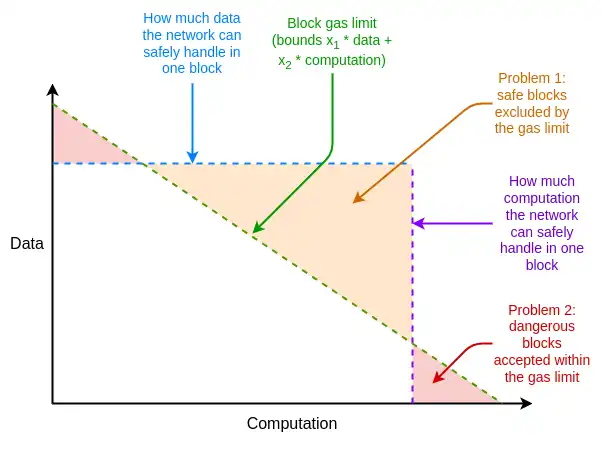

此外,还有其他与 EIP-1559 无关的以太坊资源定价的弱点,但可以通过对 EIP-1559 的调整来解决。其中一个主要问题是平均情况与最坏情况的差异:以太坊中的资源价格必须设置得能够处理最坏情况,即一个区块的全部 gas 消耗占用一个资源,但实际的平均使用远低于此,导致了低效。

什么是多维 Gas,它是如何运作的?

解决这些低效问题的方案是多维 Gas:为不同资源设定不同的价格和限制。这个概念在技术上独立于 EIP-1559,但 EIP-1559 的存在使得实现这一方案更为容易。如果没有 EIP-1559,最优地打包一个包含多种资源约束的区块就是一个复杂的多维背包问题。而有了 EIP-1559,大多数区块在任何资源上都不会达到满负荷,因此「接受任何支付足够费用的交易」这样简单的算法就足够了。

目前我们已经有了用于执行和数据块的多维 Gas;原则上,我们可以将其扩展到更多维度:如 calldata(交易数据),状态读取 / 写入,和状态大小扩展。

EIP-7706 引入了一种新的 gas 维度,专门针对 calldata。同时,它还通过将三种类型的 gas 统一到一个(EIP-4844 风格的)框架中,简化了多维 Gas 机制,从而也解决了 EIP-1559 的数学缺陷。EIP-7623 是一种更为精准的解决方案,针对平均情况与最坏情况的资源问题,更严格地限制最大 calldata,而不引入整个新维度。

一个进一步的研究方向是解决更新速率问题,寻找一种更快速的基础费用计算算法,同时保留 EIP-4844 机制所引入的关键不变量(即:在长期内,平均使用量正好接近目标值)。

现有研究链接

- EIP-1559 FAQ: EIP-1559 FAQ

- 关于 EIP-1559 的实证分析: Empirical analysis

- 允许快速调整的改进提案: Proposed improvements

- EIP-4844 FAQ 中关于基础费用机制的部分: EIP-4844 FAQ

- EIP-7706: EIP-7706

- EIP-7623: EIP-7623

- 多维 Gas: Multidimensional gas

剩下的工作和权衡是什么?

多维 Gas 的主要权衡有两个:

- 增加协议复杂性:引入多维 Gas 会使协议变得更复杂。

- 增加填充区块所需的最优算法复杂性:为了使区块达到容量的最佳算法也会变得复杂。

协议复杂性对于 calldata 来说相对较小,但对于那些在 EVM 内部的 Gas 维度(如存储读取和写入)来说,复杂性就会增加。问题在于,不仅用户设置 gas 限制,合约在调用其他合约时也会设置限制。而目前,它们设置限制的唯一方式是单维的。

一个简单的解决方案是将多维 Gas 仅在 EOF 内部可用,因为 EOF 不允许合约在调用其他合约时设置 gas 限制。非 EOF 合约在进行存储操作时需要支付所有类型 Gas 的费用(例如,如果 SLOAD 占用区块存储访问 gas 限制的 0.03%,那么非 EOF 用户也会被收取 0.03% 的执行 gas 限制费用)。

对多维 Gas 进行更多研究将有助于理解这些权衡,并找到理想的平衡点。

它如何与路线图的其他部分互动?

成功实施多维 Gas 可以大大降低某些「最坏情况」的资源使用,从而减少优化性能的压力,以支持例如 STARKed 哈希基础的二叉树等需求。对于状态大小增长设定一个明确的目标,将使客户端开发者在未来进行规划和需求估算变得更加容易。

如前所述,EOF 的存在使得实现更极端版本的多维 Gas 变得更加简单,因为其 Gas 不可观察的特性。

可验证延迟函数(VDFs)

它解决了什么问题?

目前,以太坊使用基于 RANDAO 的随机性来选择提议者,RANDAO 的随机性是通过要求每个提议者揭示他们提前承诺的秘密,并将每个揭示的秘密混合到随机性中来工作的。

每个提议者因此有「1 位操控权」:他们可以通过不出现来改变随机性(有成本)。这种方式对于寻找提议者来说是合理的,因为你放弃一个机会而获得两个新提议机会的情况非常少见。但对于需要随机性的链上应用程序来说,这并不理想。理想情况下,我们应该找到一个更稳健的随机性来源。

什么是 VDF,它是如何运作的?

可验证延迟函数是一种只能顺序计算的函数,无法通过并行化加速。一个简单的例子是重复哈希:for i in range(10**9): x = hash(x)。输出结果,使用 SNARK 证明其正确性,可以用作随机值。

这个思路是输入基于时间 T 可用的信息进行选择,而在时间 T 时输出尚不可知:输出只有在某人完全运行计算后才会在 T 之后的某个时刻可用。因为任何人都可以运行计算,所以不存在隐瞒结果的可能性,因此也没有操控结果的能力。

可验证延迟函数的主要风险是意外优化:有人发现以比预期更快的速度运行该函数,从而操控他们在时间 T 揭示的信息。

意外优化可以通过两种方式发生:

- 硬件加速:有人制造出比现有硬件更快运行计算循环的 ASIC。

- 意外并行化:有人找到一种方法,通过并行化运行函数以更快的速度,即使这样做需要 100 倍的资源。

创建成功的 VDF 的任务是避免这两种问题,同时保持效率实用(例如,基于哈希的方法一个问题是实时对哈希进行 SNARK 证明需要重型硬件)。硬件加速通常通过一个公共利益参与者自行创建和分发接近最佳的 VDF ASIC 来解决。

现有研究链接

- VDF 研究网站: vdfresearch.org

- 关于以太坊中 VDF 的攻击思考,2018 年: Thinking on attacks

- 针对提议的 VDF MinRoot 的攻击: Attacks against MinRoot

剩下的工作和权衡是什么?

目前,没有一种 VDF 构造能够完全满足以太坊研究人员在所有方面的要求。仍需更多工作来寻找这样的函数。如果找到了,主要的权衡就是是否将其纳入:功能性与协议复杂性及安全风险之间的简单权衡。

如果我们认为 VDF 是安全的,但最终它却不安全,则根据其实现方式,安全性将退化到 RANDAO 假设(每个攻击者 1 位操控权)或稍微糟糕的情况。因此,即使 VDF 失效,也不会破坏协议,但会破坏强烈依赖于它的应用程序或任何新协议特性。

它如何与路线图的其他部分互动?

VDF 是以太坊协议中相对自包含的一个组成部分,除了增加提议者选择的安全性外,它在(i)依赖随机性的链上应用程序以及(ii)加密内存池中也有应用,尽管基于 VDF 制作加密内存池仍依赖于尚未发生的额外密码学发现。

一个需要记住的要点是,考虑到硬件的不确定性,VDF 输出产生与需要之间会有一些「余量」。这意味着信息将在几个区块之前可用。这可以是一个可接受的成本,但在单槽最终确定或委员会选择设计中应该加以考虑。

模糊化和一次性签名:密码学的遥远未来

它解决了什么问题?

Nick Szabo 最著名的文章之一是他在 1997 年撰写的关于「上帝协议」的论文。在这篇论文中,他指出,许多多方应用依赖于「受信任的第三方」来管理互动。在他看来,密码学的作用是创建一个模拟的受信任第三方,完成同样的工作,而实际上并不需要对任何特定参与者的信任。

到目前为止,我们只能部分实现这一理想。如果我们所需的仅仅是一个透明的虚拟计算机,其数据和计算无法被关闭、审查或篡改,而隐私并不是目标,那么区块链可以实现这个目标,尽管其可扩展性有限。

如果隐私是目标,那么直到最近,我们只能针对特定应用开发一些具体的协议:用于基本身份验证的数字签名、用于原始匿名性的环签名和可链接环签名、基于身份的加密以在对可信发行者的特定假设下实现更方便的加密、以及用于查姆式电子现金的盲签名等等。这种方法要求为每个新应用进行大量工作。

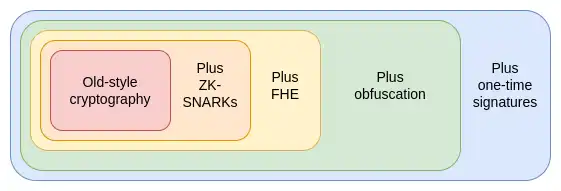

在 2010 年代,我们首次瞥见了一种不同且更强大的方法,这种方法基于可编程密码学。与其为每个新应用创建一个新协议,我们可以使用强大的新协议——具体来说是 ZK-SNARKs——为任意程序添加密码学保证。

ZK-SNARKs 允许用户证明他们持有的数据的任意声明,且证明(i)易于验证,且(ii)不会泄露除声明本身之外的任何数据。这在隐私和可扩展性上都是一个巨大的进步,我将其比作人工智能中的变换器(transformers)所带来的影响。成千上万的人年应用特定的工作,突然被这一通用解决方案所取代,这个解决方案能够处理意想不到的广泛问题。

然而,ZK-SNARKs 只是类似的三种极其强大的通用原语中的第一种。这些协议强大到当我想到它们时,它们让我想起了一组在《游戏王》中非常强大的卡片——我小时候玩过的卡片游戏和电视节目:埃及神卡。

埃及神卡是三张极其强大的卡片,传说中制造这些卡片的过程可能致命,并且它们的强大使得在决斗中禁止使用。类似地,在密码学中,我们也有这组三种埃及神协议:

什么是 ZK-SNARKs,它是如何工作的?

ZK-SNARKs 是我们已经拥有的三种协议之一,具有较高的成熟度。在过去五年中,证明者速度和开发者友好性的大幅提升使得 ZK-SNARKs 成为以太坊可扩展性和隐私策略的基石。但 ZK-SNARKs 有一个重要的限制:你需要知道数据才能对其进行证明。每个 ZK-SNARK 应用中的状态必须有一个唯一的「所有者」,他必须在场才能批准对该状态的读取或写入。

第二种没有这一限制的协议是完全同态加密(FHE),FHE 允许你在不查看数据的情况下,对加密数据进行任何计算。这使得你能够在用户的数据上进行计算,以用户的利益为出发点,同时保持数据和算法的私密性。

它还使你能够扩展如 MACI 等投票系统,以获得几乎完美的安全性和隐私保证。长期以来,FHE 被认为效率太低,无法实际使用,但现在它终于变得足够高效,开始出现实际应用。

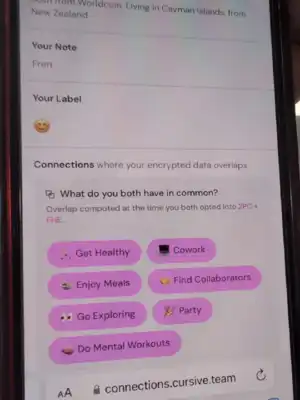

Cursive 是一款应用程序,利用双方计算和完全同态加密(FHE)进行隐私保护的共同兴趣发现。

然而,FHE 也有其局限性:任何基于 FHE 的技术仍然需要某人持有解密密钥。这可以是一个 M-of-N 的分布式设置,你甚至可以使用可信执行环境(TEEs)增加第二层防护,但这仍然是一个限制。

接下来是第三种协议,它比前两者的组合更为强大:不可区分混淆(indistinguishability obfuscation)。虽然这项技术距离成熟仍然很远,但截至 2020 年,我们已基于标准安全假设获得理论上有效的协议,最近也开始着手实现。

不可区分混淆允许你创建一个「加密程序」,执行任意计算,同时隐藏程序的所有内部细节。举个简单的例子,你可以将私钥放入一个混淆程序中,这个程序仅允许你用它来签署素数,并将此程序分发给他人。他们可以使用这个程序签署任何素数,但无法提取密钥。然而,它的能力远不止于此:结合哈希,它可以用来实现任何其他密码学原语,以及更多功能。

不可区分混淆程序唯一不能做到的,就是防止自身被复制。不过,对于这一点,前景中还有更强大的技术在等待着,尽管它依赖于每个人都拥有量子计算机:量子一次性签名(quantum one-shot signatures)。

通过结合混淆和一次性签名,我们可以构建几乎完美的无信任第三方。唯一无法仅靠密码学实现的目标,仍然需要区块链来保证的是审查抗性。这些技术不仅可以使以太坊本身更安全,还可以在其上构建更强大的应用。

为了更好地理解这些原语如何增加额外的能力,我们以投票为关键例子。投票是一个有趣的问题,因为它需要满足许多复杂的安全属性,包括非常强的可验证性和隐私性。虽然拥有强安全属性的投票协议已经存在数十年,但我们可以自我加大难度,要求设计能够处理任意投票协议:如二次投票、成对限制的二次资助、集群匹配的二次资助等等。换句话说,我们希望「计票」步骤成为一个任意程序。

首先,假设我们将投票结果公开放在区块链上。这使我们获得了公开可验证性(任何人都可以验证最终结果是否正确,包括计票规则和资格规则)和审查抗性(无法阻止人们投票)。但我们没有隐私。

接着,我们添加了 ZK-SNARKs,现在,我们有了隐私:每一票都是匿名的,同时确保只有授权选民可以投票,每位选民只能投票一次。

接下来,我们引入了 MACI 机制,投票被加密为中央服务器的解密密钥。中央服务器负责进行计票过程,包括剔除重复投票,并发布 ZK-SNARK 证明结果。这保留了之前的保证(即使服务器作弊!),但如果服务器诚实,它还增加了一种抗强迫的保证:用户无法证明他们的投票方式,即使他们想这样做。这是因为虽然用户可以证明他们的投票,但他们无法证明自己没有投票以抵消该票。这防止了贿赂和其他攻击。

我们在 FHE 中运行计票,然后进行 N/2-of-N 阈值解密计算。这使得抗强迫保证提升至 N/2-of-N,而不是 1-of-1。

我们将计票程序进行混淆,并设计混淆程序,使其只有在获得授权时才能输出结果,授权方式可以是区块链共识的证明、某种工作量证明,或两者结合。这使得抗强迫保证几乎完美:在区块链共识情况下,需有 51% 的验证者串通才能破解;在工作量证明情况下,即使所有人串通,重新以不同选民子集进行计票以试图提取单个选民的行为也将极为昂贵。我们甚至可以让程序对最终计票结果进行小幅随机调整,以进一步增加提取单个选民行为的难度。

我们添加了一次性签名,这是一种依赖于量子计算的原语,允许签名仅用于一次特定类型的信息。这使得抗强迫保证变得真正完美。

不可区分混淆还支持其他强大的应用。例如:

- 去中心化自治组织(DAOs)、链上拍卖以及其他具有任意内部秘密状态的应用。

- 真正的通用可信设置:某人可以创建一个包含密钥的混淆程序,并运行任何程序并提供输出,将 hash(key, program) 作为输入放入程序中。给定这样的程序,任何人都可以将程序 3 放入自身中,结合程序的预先密钥和他们自己的密钥,从而扩展设置。这可用于为任何协议生成 1-of-N 的可信设置。

- ZK-SNARKs 的验证仅需一个签名:实现这一点非常简单:设置一个可信环境,让某人创建一个混淆程序,只有在有效的 ZK-SNARK 情况下才会使用密钥签署消息。

- 加密的内存池:加密交易变得非常简单,这样交易只有在未来发生某个链上事件时才能被解密。这甚至可以包括成功执行的可验证延迟函数(VDF)。

借助一次性签名,我们可以使区块链免受最终性反转的 51% 攻击,尽管审查攻击仍然可能。类似一次性签名的原语使得量子货币成为可能,从而解决了无区块链的双重支付问题,尽管许多更复杂的应用仍需要链。

如果这些原语能变得足够高效,那么世界上大多数应用都可以实现去中心化。主要的瓶颈将是验证实现的正确性。

以下是一些现有研究的链接:

- 不可区分混淆协议(2021): Indistinguishability Obfuscation

- 混淆如何帮助以太坊: How Obfuscation Can Help Ethereum

- 第一次已知的一次性签名构造: First Known Construction of One-Shot Signatures

- 混淆的尝试实现(1): Attempted Implementation of Obfuscation (1)

- 混淆的尝试实现(2): Attempted Implementation of Obfuscation (2)

还有哪些工作要做,以及权衡是什么?

还有很多工作要做,不可区分混淆仍然非常不成熟,候选构造的运行速度慢得惊人(如果不是更多的话),以至于无法在应用中使用。不可区分混淆以「理论上」多项式时间而闻名,但在实际应用中,其运行时间可能比宇宙的生命周期还长。最近的协议在运行时间上有所缓解,但开销仍然太高,无法进行常规使用:一位实施者预计运行时间为一年。

量子计算机甚至还不存在:你在互联网上看到的所有构造,要么是无法进行超过 4 位运算的原型,要么根本不是实质性的量子计算机,虽然它们可能有量子部分,但无法运行诸如 Shor 算法或 Grover 算法这样的有意义计算。最近有迹象表明,「真正的」量子计算机离我们并不遥远。然而,即使「真正的」量子计算机不久后出现,普通人要在自己的笔记本电脑或手机上使用量子计算机,可能还要等几十年,才能在强大的机构能够破解椭圆曲线密码学的那一天。

对于不可区分混淆,一个关键的权衡在于安全假设,存在使用特殊假设的更激进设计。这些设计通常具有更现实的运行时间,但特殊假设有时最终会被破坏。随着时间的推移,我们可能会更好地理解格,从而提出不易被破坏的假设。然而,这条路更具风险。更保守的做法是坚持使用那些安全性可证明减少到「标准」假设的协议,但这可能意味着我们需要更长时间才能获得足够快速运行的协议。

它如何与路线图的其他部分互动?

极其强大的密码学可能会彻底改变游戏,例如:

- 如果我们获得的 ZK-SNARKs 的验证与签名一样简单,那么我们可能不再需要任何聚合协议;我们可以直接在链上进行验证。

- 一次性签名可能意味着更安全的权益证明协议。

- 许多复杂的隐私协议可能仅需一个隐私保护的以太坊虚拟机(EVM)来替代。

- 加密的内存池变得更易于实现。

起初,益处将在应用层出现,因为以太坊的 L1 本质上需要在安全假设上保持保守。然而,仅应用层的使用就可能是颠覆性的,就像 ZK-SNARKs 的出现一样。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。